Bill Little Articles part II

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

At Last , the letter “E”

-

Down to the Bone,

-

The Victory lap,

-

A Birthday and a Mexican Dinner

-

A PLACE IN THE HALL — STEVE MCMICHAEL,

-

A Tale of two Houses

-

Dancing With the Stars

-

The End of the Game

-

The tie that Binds

9.02.2012 | Football

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: AT LAST, THE LETTER ‘E’

Sept. 2, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It is interesting that the last letter in “RISE” – the Longhorns’ team theme for the 2012 season – stands for the most important word of all.

The “E” is for emotion. “R” was for relentless, “I” was for intensity, “S” was for swagger (the coaches wanted “sacrifice”). And Saturday night in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, the team made its debut.

Webster will tell you that “emotion” has many meanings, and that was well-evident in the 37-17 victory over Wyoming and the events that surrounded it. The first surge came before the day ever arrived, when AT&T U-Verse added roughly 10 million television viewers nation-wide (800,000 in Texas alone) to the households where the Longhorn Network is available. Then, the firing of Smokey the Cannon signaled the arrival of the team at the stadium Saturday, and the players took a walk through hundreds of fans, including the Longhorn band and the Texas Pom and cheerleaders down 23rd Street and into the gates of the Red McCombs Red Zone at the north end of the stadium.

Shortly before 7 p.m., most of the crowd of over 100,000 was there for the emotional (there is that word again) moment when Coach Royal and his wife, Edith, were introduced as the honorary captains, and the 88-year-old man rose from his golf cart and stood with the Longhorn game captains for the coin toss.

All of that done, it was now time to see if the 2012 team was ready to validate their theme. And for awhile, the jury was still out on whether they were going to be able to embrace that vital final phrase.

Emotion, you see, is defined as one of the three fundamental properties of the human mind, the other two being volition and intellect. So you can have the desire, and you can have the knowledge, but to excel in anything, you must also have emotion. And you darn sure can’t play the game of football without emotion.

And for awhile, the team that wanted so badly to earn the right to swagger, was seemingly without any. The ‘Horns had trailed, 3-0, and after taking a 7-3 lead, watched a good Wyoming team steal their swagger and march right down to a 9-7 lead. Emotion finally arrived when Chris Whaley blocked the extra point try. Then, the fiery leader of the defense, Kenny Vaccaro, gave the crowd – and the team -something to hang their emotional hats on. An interception and a long return and another play where he blitzed and forced the Wyoming quarterback into a bad pass that Carrington Byndom intercepted, swung the emotional tide in the Longhorns’ favor. Texas scored 24 unanswered points before the Cowboys cut the lead to 31-17.

The offense turned to a power running game with Joe Bergeron and Malcolm Brown leading the way, complimented by some speed sweeps by D. J. Monroe and highlighted by a brilliant touchdown reception by Jaxon Shipley. Bergeron rushed for 110 yards and Brown for 105, the second time in their young careers that the sophomore running backs have both had 100-yard plus games.

Quarterback David Ash had an efficient night, mixing 20 pass completions for 156 yards with the running game. But it would be the defense which would have to come up with a major fourth down stop inside the ten yard line as Wyoming threatened to cut the lead to just seven points after Ash lost a fumbled snap at his own 35 early in the fourth quarter with the ‘Horns leading, 31-17. After the defensive stop, the offense – fueled by Bergeron’s 54-yard run on the first play – drove 91 yards for the final score of the 37-17 victory.

In the end, Mack Brown got his 14th opening win in his 15 seasons, and saw just about what he expected. Wyoming looked to be better than the Cowboy teams the Longhorns have faced in two of the past four years, and the ever-present excessive heat didn’t appear to sap the men from the mountains all that much. The Longhorns’ hard summer training from strength and conditioning coach Bennie Wylie also shined, as the ‘Horns, too, withstood the heat.

The game was what coaches look for in an opener – a pretty much injury-free victory which leaves them lots to work on as they head to week two against a Bob Davie-coached New Mexico team next week.

What is important about the words represented in RISE is that they have to be a commitment for the season, not just a catchy phrase to produce a wrist band. Themes, to be successful, have to mean something every day. That’s why the 2005 “Take Dead Aim” mattered so much. Mack applied it to everything the players did, from their focus on life to their focus on the game of football.

So it must be with RISE, if it is to work. You do have to be relentless. You do have to have intensity, and after Saturday the players should fully understand that if they want to swagger, they have to do something to earn that right.

Finally, in the end, we arrive at emotion. Emotion doesn’t manifest itself by the shouting and the tumult, and there is strong evidence that controlled emotion has its place right along with the jumping-up-and-down in your face shouting. But however you define it and however you attain it, you absolutely must have it. Of those three senses, volition gets you there, and intellect tells you how and what to do.

It is, however, in the state of emotion that greatness is achieved. And that, as we understand it, is the bottom line to what this team has said it wants to achieve.

08.27.2008 | Football

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: DOWN TO THE BONE

Aug. 27, 2008

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

(NOTE: Forty years ago, the Texas Longhorns were preparing to open the 1968 football season against the University of Houston, which was then a power as an independent in college football, and a significant threat to football supremacy in a state which for more than half a century had been dominated by The Southwest Conference. Texas was coming off of three consecutive seasons in which the Longhorns had lost four games in each. Darrell Royal had given his backfield coach, Emory Bellard, an assignment to create an offense that would put a talented stable of runners to their best use. Here, reprinted from the book, “Stadium Stories — Texas Longhorns” by Bill Little, is an excerpt from a chapter that tells the story of that pivotal change in Longhorn history, and in the history of college football.)

Emory Bellard sat in his office, down the narrow, eggshell-white corridor that was part of an annex linking old Gregory Gymnasium with a recreational facility for students. There were two exit doors, one at the glassed-in front of the two-story building, and the other at the end of the hall.

Summer in 1968 was a time for football coaches to relax, and to prepare for the upcoming season. Most of Bellard’s cohorts on Darrell Royal’s staff were either on vacation or had finished their work in the morning and were spending the afternoon at the golf course at old Austin Country Club.

Texas football had taken a sabbatical from the elite of the college ranks in the three years before. From the time Tommy Nobis and Royal’s 1964 team had beaten Joe Namath and Alabama in the first night bowl game, the Orange Bowl on January 1 of 1965, Longhorn football had leveled to average. Three seasons of 6-4, 7-4 and 6-4 had followed the exceptional run in the early 1960s.

Despite an outstanding running back in future College Football Hall of Famer Chris Gilbert, the popular “I” formation with a single running back hadn’t produced as Royal and his staff had hoped. So with the coming of the 1968 season, and the influx of a highly-touted freshman class who would be sophomores (this was before freshmen were eligible to play on the varsity), Royal had made a switch in coaching duties.

Bellard, who had joined the staff only a season before after a successful career in Texas high school coaching at San Angelo and Breckenridge, was the new offensive backfield coach.

Bellard had gone to Royal with the idea of switching to the Veer, an option offense that had been made popular in the southwest at the University of Houston. As the Longhorns had gone through spring training, they had returned to the Winged-T formation, which Royal had used so successfully during the early part of the decade.

So, as the summer began, the on-going question was, who was going to play fullback, the veteran Ted Koy, or the sensational sophomore newcomer Steve Worster? With Gilbert a fixture at running back, even in the two-back set of the Veer formation, only one of the other two could play.

And that is how, on that summer afternoon, the conversation began.

“So, who are you going to play, Koy or Worster?” the question was asked. Bellard took a draw on his ever-present pipe, cocked his chair a little behind the desk that faced the door, and said, “What if we play them both?” He took out a yellow pad and drew four circles in a shape resembling the letter “Y.”

“Bradley,” he said, referring to heralded quarterback Bill Bradley, as he pointed to the bottom of the picture. “Worster,” he said, indicating a position at the juncture behind the quarterback. “Koy”, he said as he dotted the right side, “and Gilbert,” indicating the left halfback.

Royal had told Bellard he wanted a formation that would be balanced, and that, unlike the Veer which was a two back set, would employ a “triple” option with a lead blocker. On summer mornings, Bellard would set up the alignments inside the old gymnasium next to the offices, using volunteers from the athletics staff as players.

As fall drills began, the formation was kept under wraps. Ironically, Texas opened the season that year against Houston. It was only the second meeting of the two. The Longhorns had won easily in 1953, but the Cougars had established themselves as an independent power that was demanding respect from the old guard Southwest Conference.

A packed house of more than 66,000 overflowed Texas Memorial Stadium for the game, which ended in a 20-20 tie. The debut of the new formation didn’t exactly shock the football world.

A week later, Texas headed to Texas Tech for its first conference game, and found itself trailing 21-0 in the first half. It was at that point that Royal made the first of a series of moves that would change the face of his offense and the face of college football, for that matter.

Bill Bradley was the most celebrated athlete in Texas in the mid-1960s. He was a football quarterback, a baseball player, could throw with either hand and could punt with either foot. He was a senior, and when Royal unveiled the new formation, he thought that Bradley’s running ability would make him perfect as the quarterback who would pull the trigger.

But trailing in Lubbock, Royal made one of the hardest decisions of his coaching career. He pulled Bradley and inserted a little-known junior named James Street.

A signal caller from Longview, Street had been an all-Southwest Conference pitcher in baseball the spring before, but no one could have expected what was about to happen.

Street brought Texas back to within striking distance of the Raiders, closing the gap to 28-22 before Tech eventually won, 31-22.

Back home in Austin, the staff met to adjust where the players lined up in the new formation. In a debate that was won by offensive line coach Willie Zapalac, the fullback position alignment was adjusted. Worster, who had been lined up only a yard behind the quarterback in the original formation, was moved back two full steps so he could better see the holes the line had created as the play developed.

Against Oklahoma State the next week, Texas won, 31-3. Nobody realized it at the time, but that would be the start of something very big. With Street as the signal caller, that win was the first of 30 straight victories, the most in the NCAA since Oklahoma had set a national record in the 1950s, and a string that held as the nation’s best for more than 30 years.

While the Oklahoma State game started the streak, the Oklahoma game the next week would become known as, “The Game That Made the Wishbone.”

Texas was 1-1-1 as it headed to Dallas to play the Sooners, and with only 2:37 remaining in the game, Street and Royal’s new offense was at their own 15-yard line, trailing 20-19. A legend was about to be born.

Street hooked up with tight end Deryl Comer for pass completions of 18, 21 and 13 yards, and then connected with Bradley, who had moved to split end after the Tech game, for 10 yards to the Oklahoma 21-yard line. Only 55 seconds remained as Worster crashed through a big hole to the seven.

On the sidelines, assistant coach R. M. Patterson corralled a wide-eyed Happy Feller, his sophomore field goal kicker, and told him that if the Longhorns didn’t score a touchdown on the next play, he was going to have to hurry out and kick, because Texas was out of timeouts.

While Texas was struggling on the field in the mid-1960s, the recruiting season of 1967 had netted the most successful recruiting haul in Southwest Conference history. The linchpin of the group was Steve Worster, a powerful running back from Bridge City. The recruiting class would forever be known as “The Worster Crowd.”

With time running out at the Oklahoma 7-yard line, James Street handed the ball to Steve Worster. Two Sooners tried to stop him, but the bruising fullback who was on his way to stardom dragged them with him as he dived into the end zone. Only 39 seconds remained. Texas won, 26-20. The next week the Longhorns pounded Arkansas.

In one of his post-game meetings with the sportswriters at the Villa Capri Motor Hotel (which stood where the UT indoor practice facility is located today) following the game, a writer asked Royal what he called the new offense.

“I don’t know,” he said. “What do you guys think?”

Mickey Herskowitz of the Houston Post followed several other suggestions by saying, “Well, it looks like a chicken pully-bone.”

“Okay,” said Royal. “The Wishbone.”

The new-fangled offense would team with a solid Longhorn defense to dominate the era. Street would record the best won-loss record as a quarterback in Texas history, starting 20 games and winning all of them.

The 1968 team would finish third in the country, pounding No. 8 Tennessee, 36-13, in the Cotton Bowl. The offense had become unstoppable. Following the 20-20 tie with Houston in the season opener, Cougar coach Bill Yeoman had told the media, “I wish we had a chance to play them again.” That prompted irreverent sportswriters to comment at half-time of the New Year’s Day game in Dallas, “somebody call Yeoman and tell him to bring his team on up…this thing is over.”

11.18.2011 | Football

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: THE VICTORY LAP

Nov. 18, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It has always seemed fitting that Senior Day and the game where they honor the newest members of the men’s and women’s Longhorn Halls of Honor usually occur on the same weekend. Because each is about accomplishment. Each is about memories.

David Thomas, the stellar tight end who was part of the 2005 National Championship team, spent a little time with the current Longhorn team Thursday, and shared his memories of his Senior Day that season.

“Ahmard Hall and I looked at each other as we were finishing the “Eyes of Texas” after the game, and decided to take a victory lap around the stadium. All of the fans were still there, and I remember slapping hands with them all the way around the stadium. It is a day you never forget,” he said.

Saturday night’s game with Kansas State will be the final game in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium for this year’s seniors, but in many ways it has a different feel to it because there will be two regular season games and a bowl trip that will follow. So the end may be near, but there is still a long way to go as far as the legacy these seniors will leave.

Still, this is a special night, if as much for the parents as it is for the players. Just prior to the game, each Longhorn senior will come out of the tunnel, shake hands with their head coach, Mack Brown, and then head into the end zone for hugs with family members.

For the families, and for us, it is a realization of a passage – the moment when you realize that something that had become a constant in your life will be no more.

Can it really be that Blake Gideon, the son of a coach and a heroic mother-cancer survivor, will be leaving after starting every game of his college career? We have all come to know, not only the players, but their folks as well. We’ve learned of the social work in foreign lands of Dr. and Mrs. Acho, just as we have celebrated their sons, Emmanuel and Sam, as the ultimate student athletes, on and off the field. Fozzy Whitaker’s mom is a hero for us, for rearing a son after his dad died when he was young, and loaning us that son as a champion and a heart-warming story in our lives.

And there are Paul and Michelle Tucker, who sent not only son Justin, but swimmer Samantha, to follow them and a long family tree of Longhorns. Like Blake Gideon, Justin has kicked a football, either on a kickoff, a placement or a punt, in every one of the last four dozen Texas football games.

It was Dr. Tucker, one of Austin’s premier cardiologists, who came out of the stands when Justin was in high school to help save Matt Nader’s life on the playing field. Folks called it a miracle, and we are told that is what happens when The Higher Power uses the hands and the knowledge of His creatures here below to do something extraordinary.

Miracles also unite those gifted hands with the power of an individual’s will, which brings us to Blaine Irby. We watched him come from California, and watched his wonderful parents transition from loved ones who anticipated one career beyond college for their son to a vigil that he would, in time, walk normally.

The doctors and rehabilitation specialists will tell you that Blaine Irby is a miracle; and in that space, we marvel, and we celebrate.

Fifteen members of this senior class have played in a combined 567 games, with 217 starts. Besides Blake, Justin, Fozzy, Emmanuel, and Blaine they include Cody Johnson (who unselfishly moved to fullback this year), David Snow (who has played center, guard and tackle in the offensive line), Tray Allen, Kheeston Randall, Keenan Robinson, and Christian Scott.

Others who have contributed significantly include deep snapper Alex Zumberge*, fullback Jamison Berryhill, Mark Buchanan, Ahmard Howard, John Paul Floyd, Luciano Martinez, Patrick McNamara, John Osborn, Sam Walker, Trey Wier* and Nick Zajicek.

The weekend activities for the Hall of Honor inductions will see the women honor administrator Christine Plonsky, as well as such superstars as Sonya Richards-Ross and Cat Osterman, among others.

Former Longhorn football players who are being inducted span generations. Bill Zapalac was the son of former coach Willie Zapalac, and his brother Jeff also lettered at Texas. Bill played defense in the 1968-70 era when the Longhorns won two National Championships and 30 straight games. Lance Gunn was an all-American safety in the early 1990s, and Pat Fitzgerald was a star tight end on three conference championship teams. He was an all-American on the field, and a National Football Foundation Scholar Athlete as well.

The journey which brings them all together is unique, with a common thread being Texas Longhorn athletics. It is a reminder that we are – all of us – somehow connected. There is no better story of that than Kris Kubik, the Longhorns’ longtime assistant swim coach who has been at Eddie Reese‘s side for every conference and national championship the storied program has achieved. And so it was Kris who gave us this story.

In all of the years of the men’s Longhorn Hall of Honor inductions, dating back to 1957, only one Longhorn, who neither played or even attended UT whose only participation has been as an assistant coach has ever been inducted. That person was Darrell Royal’s right-hand man and defensive guru, the late Mike Campbell. Mike last coached at Texas in 1976, and he died in 1998. So how do the lives of two men, the swimmer Kris Kubik and the football coach Mike Campbell intertwine?

“I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee,” Kris wrote. “One of my best friends growing up (and still to this day) is a fellow named Bill Daniel, Jr. Bill’s father attended Central High School in Memphis, graduating around 1940 or so. He went on to Ole Miss to play football, but had to leave to fly for the Air Force in WWII, and then returned to play football at Ole Miss once again. His best friend at Central High and his roommate at Ole Miss and his “brother” in the Air Force was – drum roll please – Mike Campbell. It completely warms my heart to know that connection….”

What we have learned, and are reminded by the ceremonies concerning the Hall of Honor and the hugs from families on Senior Day, is that we all are connected. There are those in the arena who use their unique gifts to excel. Because of them, there are those of us – family, friends and fans – whose role is simply to absorb the miracles, and the talents, which we see.

Those whom we honor Saturday night will never pass this way in this same setting again. But they return (in the case of the Hall of Honor inductees), or they leave with their memories and their legacy. And that, after all, is their gift to us.

07.06.2012 | Football

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: A BIRTHDAY AND A MEXICAN DINNER

July 6, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Of all the words in the English language, the word “unique” is rare. It is rare because it requires, nor will it accept, no surrounding superlatives. You can’t say “very unique,” “so unique” or even “extremely unique.” Unique is…well, unique.

The subject came up a couple of times Friday as a group of about 50 former players gathered to celebrate the 88th birthday of their coach, Darrell Royal. With each moment, and each comment, Royal’s impact on their lives – and the lives of all those associated with The University of Texas football program – was a reminder of a meaning and a strength that transcends years.

The flowers on the counter in the party room of Matt’s El Rancho further emphasized the occasion, as the restaurant which has been so connected to Longhorn athletics for all these years prepared to celebrate its 60th birthday on Saturday.

Mack Brown had started the day for Darrell and Edith Royal with a good-wishes phone call from his house in the mountains of North Carolina. President Bill Powers was rushing from a meeting to try to arrive in time.

Players who spanned an era of Texas football from 1957 through 1976 each spoke briefly. Former Longhorn quarterback T Jones was there, thanking Royal for hiring him as a 26 year old assistant coach when he came to Texas in December of 1956. Fred Akers, who joined Royal’s staff as an assistant in 1966 and later returned as the Longhorns’ head coach himself, thanked Royal for plucking him from the ranks of high school coaches and “giving me a chance to become a college coach.”

With only a handful of exceptions, the men in the room had either played or coached for Royal during one of the most successful runs in the history of college football. But to many, he had been more than a coach.

“It may be your birthday,” said Jim Bob Moffett (who played on Royal’s first teams), “but to us, it is a little like Father’s Day. Because you have been like a father to a lot of us.”

As the sun bathed the courtyard of the restaurant beyond the latticed windows, the clock turned back. For Royal, it was a celebration of a variance of “family.” Many of these same men, including former basketball assistant coach Eddie Oran, see Royal on a regular basis. They follow a schedule, taking turns taking him to lunch. There’s a table at a restaurant near the facility where he and Edith live that’s held available daily for him to drop in for a meal or a cold beverage.

Friday’s gathering was also the anniversary of another Texas tradition, because it was 50 years ago, in the summer of 1962, when Royal and a local sporting goods salesman named Rooster Andrews introduced the modern football world to the uniform color of burnt orange.

Urban legend would eventually suggest that Royal, who was known for his affinity for running the football, created the color to deceive opponents because of the similar colors of the new home jerseys and the leather footballs.

Nothing, Royal said Friday, could be further from the truth.

Ronnie Landry, an offensive lineman in the 1960s who was a freshman in 1962, remembers a couple of varsity players modeling the jerseys. Pat Culpepper, who was a star senior linebacker, remembers nothing close to the stir caused by some of the new uniforms of today.

The truth is, Royal had tired of the orange color which Texas had been wearing since World War II. It was a darker version of the light orange worn by Tennessee, and no one manufacturer seemed to be able to match the color year after year.

That was what prompted Royal to ask Rooster to research the color, and when he did, he came to realize he was seeking something that had already been created.

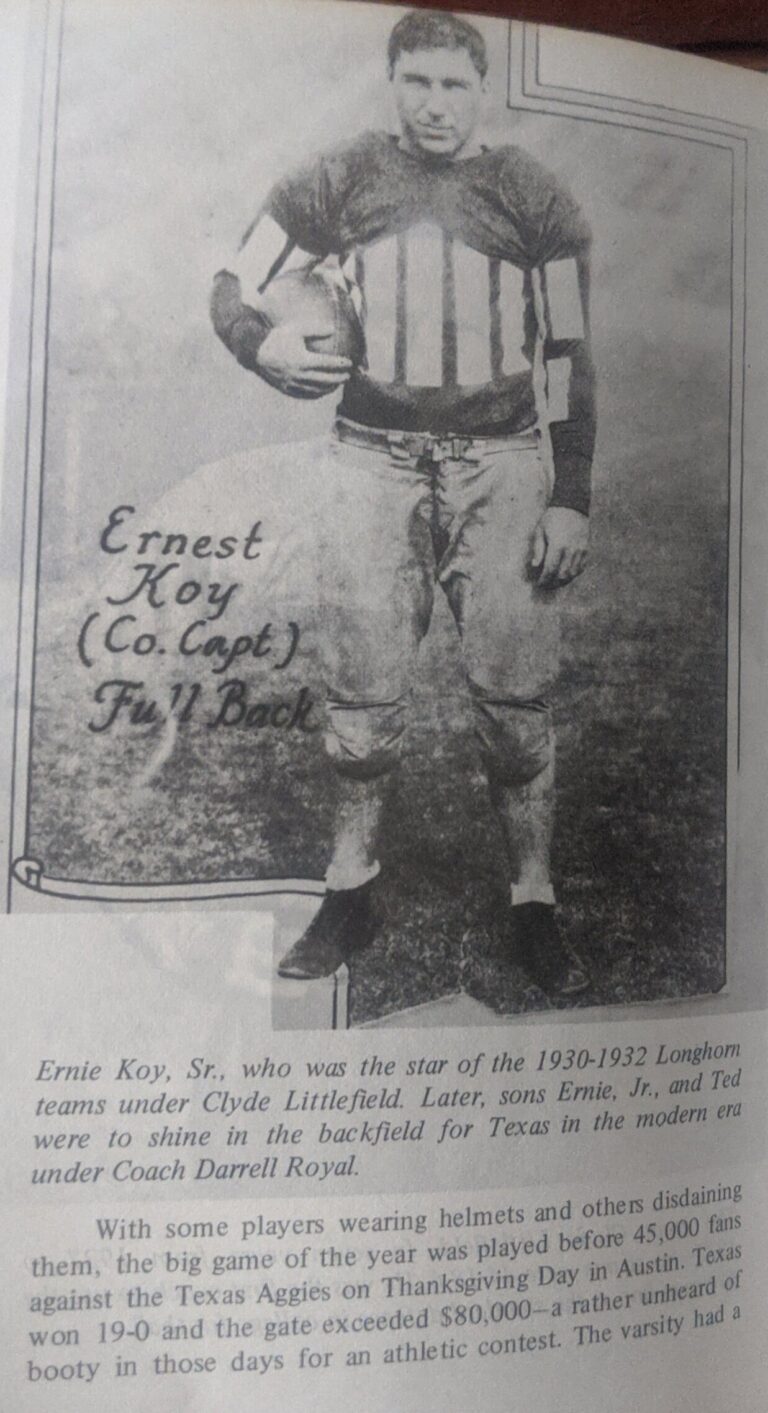

In 1928, Texas coach Clyde Littlefield had sought a resolution of a problem with the school colors. The orange dye used at the time tended to fade when washed, thus reducing it almost to a lemon yellow color. Thus came the derogatory term “Yellow bellies” to describe the proud Longhorn players. Littlefield went to a friend in the garment business in Chicago, and together they created the burnt orange color and it was officially named “Texas Orange.”

That was the color Texas wore until the 1940s. It seems the dyes used for the dark orange color came from Germany, and during World War II that wasn’t available. So the lighter orange had to suffice, until Royal and Andrews stepped in.

“I was looking for something that would be only ours,” Royal said Friday. “Besides, it was our original color.”

When the Longhorns take the field in September to open the 2012 season, it will have been 50 years since the burnt orange color arrived on the college football landscape. The myth about the color of the football still surfaces from time to time, but there are some interesting figures in that regard. The Longhorns, of course, wear the orange jerseys at home, as well as in some bowl games and as the home team every odd year against Oklahoma in Dallas.

During the first three years Texas wore the new jerseys, from 1962 through 1964, Texas was 15-2 (with a win over Roger Staubach and Navy in the Cotton Bowl) while wearing orange, and 15-0-1 (with a win over Joe Namath and Alabama in the Orange Bowl) while wearing white.

In the ten years between 1962 and 1971, the Longhorns were 49-12-1 in orange and 39-6-1 in white, and Royal was named coach of the decade by ABC-TV. So much for the theory of deceptive trade practices.

As Royal posed for pictures with legendary players such as James Street and Bill Bradley and the noon luncheon began to drift into the remains of the work day on a hot July 6 afternoon, Royal thought of one more thing about the jerseys that pretty well summed up them, and him.

“I wanted,” he said, “for it to be unique.”

And that, without superlatives, is Darrell Royal at 88.

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: A PLACE IN THE HALL — STEVE MCMICHAEL

April 30, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

If it is as they say — that there is a thin veil between life and death — then somewhere from a place beyond E. V. McMichael is smiling right now.

It has been a long time since that night in 1976 when young Steve McMichael was returning to Austin after starting his very first game as a Texas Longhorn defensive end against the Texas Tech Red Raiders in Lubbock. A lot would change that late October night. The night before the game, Darrell Royal would confide to some close associates that he likely would retire as the Texas head football coach following the season.

Earl Campbell, the star of the team, would re-injure a hamstring and would miss the next four games in what would turn out to be a 5-5-1 season. For Steve McMichael, a sturdy young freshman from Freer who had been considered for the tight end position, his first start as a Longhorn had ended in a 31-28 loss to the Red Raiders.

But that night — October 30, 1976 — young Steve would learn the difference between the game of football and the reality of life. That night, E. V. McMichael, an oil field superintendent, was shot to death outside his home in South Texas.

In the years that would follow, Steve would stick with the game E. V. had helped teach him. Where it was football that had brought him to The University of Texas, it would be Steve’s drive and dedication that would carry him to the greatest heights of the game.

That is why, on Wednesday, when Steve McMichael was announced as the Texas Longhorns’ 15th player and 17th overall inductee (including coaches D. X. Bible and Darrell Royal) into the National Football Foundation’s College Hall of Fame, you have to figure there was a loud cheer somewhere beyond the sky.

“I will never be able to thank The University of Texas enough for what it did for me during that time,” McMichael recalled from his home in Chicago, where he was a star in the NFL for the Bears and is now the head coach of the arena league Chicago Slaughter. “My ‘old man’ put me on the road, but if it hadn’t have been for Texas, I have no idea where I would be right now.”

McMichael joins a class that includes, among others, Tim Brown of Notre Dame, Major Harris of West Virginia, Chris Spielman of Ohio State, Curt Warner of Penn State, Gino Torretta of Miami and Grant Wistrom of Nebraska.

There were those, during his playing days at Texas, who would swear that McMichael was the poster boy for the old cartoon showing a grizzled guy with a menacing look with the take off on the Bible scripture saying, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of death, I will fear no evil…’cause I am the meanest dude in the valley.”

Back at Texas Tech his junior year, when the Red Raiders’ spirit group came to the airport and rolled out a red carpet, McMichael and his fellow tackle Bill Acker took one look at the welcome gesture, then pushed through the red-and-black clad students and walked around the carpet. Texas won the next day, 24-7.

His senior year in 1979, as part of perhaps the best defense in Texas history (it allowed an average of only nine points per game), McMichael personally dominated the 1978 Heisman Trophy winner Billy Sims in the Longhorns’ 16-7 victory over the Sooners. Sims gained only 73 yards on 20 carries, and McMichael registered 13 tackles — nine against the running game.

McMichael totaled 133 tackles during his senior season, and posted 369 tackles, 30 sacks, 40 tackles behind the line, 99 quarterback pressures and 11 caused fumbles during his career as a Longhorn.

In the NFL, McMichael’s name would become famous in Chicago, where he would help lead the Bears to some of their greatest moments, including a Super Bowl win in the 1985-86 season. Drafted and later cut by the New England Patriots in 1980, McMichael rebounded to become a two-time Pro Bowler in Chicago. He played 14 years in the league, retiring in 1994 after a final season with Green Bay. He set a Bears’ record by playing in 191 consecutive games, and during his career he registered 95 sacks and played in 213 NFL games.

He then took a spin as a professional wrestler before retiring in 1999. In 2001, he returned to Chicago where he has hosted the Chicago Bears pre- and postgame shows on the local ESPN radio affiliate.

His Chicago Slaughter Professional Arena team is 7-0 and has clinched the Western Division of the Continental Indoor Football League, doing so with a 78-25 victory over Milwaukee last Saturday.

A member of the Longhorn Hall of Honor, the Texas High School Sports Hall of Fame and the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame, McMichael is involved in numerous charities, most notably the Fisher House Foundation and other organizations that support wounded soldiers and their families.

McMichael becomes the second member of his Longhorn era to be inducted into the NFF Hall of Fame, joining safety Johnnie Johnson, who was enshrined in 2007. Upon his induction during the December festivities in New York, Johnson allowed that he would have made a lot more tackles, had McMichael not made them all before they could get into the secondary.

“I can tell you this,” McMichael said Wednesday. “I will be wearing orange. There is no way to describe how much this means, or how thankful I am to all of the people who helped me at Texas. All I can say is, ‘Hook ’em!'”

It is a long way from Freer, Texas, to the ballroom of the storied Waldorf Astoria in New York City. The years perhaps have dulled the pain of that night so very long ago that changed the life of a young freshman. But when Steve McMichael, his wife and new baby girl celebrate that moment in the grand old hotel, there will be a lot of pride in a lot of places, seen and unseen.

Because, you see, in his playing time at Texas and at Chicago, many people saw the tough exterior of a man carved from the dust of the land and the steel of the spirit. But what drove Steve McMichael was a wry smile that reflected someone who could see the fun side of life, even in the hard times. It was paired with a fierce determination and an unbending drive of competition.

Most of all, it was about matters of the heart — the kind which fought undaunted, perhaps bloody, but always unbowed.

09.16.2012 | Football

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: A TALE OF TWO HOUSES

Sept. 16, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

OXFORD, MS – They had come to this place – these two speedsters and catchers – from different places. One had been to the White House, the other – by his own admission – had been to his personal dog house.

And together, they were part of an accomplished team effort as Texas thrashed Ole Miss, 66-31, Saturday night before the largest non-conference home crowd in the history of the SEC school.

The defense, which would eventually yield more yardage and points than defensive coordinator Manny Diaz and his crew would have liked, set the tone for the night with linebacker Steve Edmond‘s 22-yard interception return for a touchdown on the second possession of the game for the Rebels. But it would be a balanced, big play offense that would carry the night for Texas. And right in the middle of it were the guys whose stories we started out to tell you.

The legendary Texas baseball coach Cliff Gustafson once told me, “Bill, speed don’t have a bad day.” And that would be the theme of the evening for the very balanced Longhorn attack. Wide receiver Marquise Goodwin, who was excused from practice on Thursday so that he could travel to Washington to be honored along with 1,000 other U.S. Olympians in a ceremony at the White House, arrived at the team hotel in Memphis late Friday night. Unfortunately for Ole Miss, he did not arrive late in Oxford.

Goodwin blew through the Rebel defense on a 69-yard touchdown run on the Longhorns’ first possession of the second quarter. That made the score 17-7, and Texas never looked back.

For Goodwin, it capped a week of celebrating. For fellow wideout Mike Davis, it marked a validation of revival. After a brilliant freshman year in 2010, Davis battled injuries and personal problems last year. He was nowhere close to the same guy who was a smiling, happy freshman – just getting started with a promising career two seasons ago. In January of this year, however, Mike Davis decided to change that.

“When I came back from the break,” he said with that characteristic smile in the locker room after the game at Ole Miss, “I made up my mind to leave all of that `stuff’ behind me.” Saturday, that wasn’t the only thing he left behind.

Davis caught five passes for 124 yards, including a 46-yard TD pass from David Ash. Goodwin had two catches for 102 yards, including a 55-yard TD pass. For the night, Goodwin had 80 yards rushing, 102 receiving, and 16 on a kickoff return.

Ash finished the game with 19 completions on 23 tries for 326 yards and four TDs. Nine different players caught passes. But as impressive as the 326-yard passing output was, it was a punishing running game which set the stage.

For several years, Mack Brown has expressed a desire to get back to the 50 percent-50 percent pass-rush yardage output, and Saturday night was about as close as you can get. With Malcolm Brown leading the stats with 128 yards on 21 carries and two touchdowns, Joe Bergeron doing bruising work early for 48 yards on eleven carries and Jonathan Gray carrying the workload for 50 yards on a Case McCoy-engineered drive in the fourth quarter, Texas ran for 350 yards and four TDs.

The 66 points marked the most by a Texas team since the 2005 National Champions hung 70 on Colorado in the Big 12 Championship game. While the defense left unsatisfied because of surrendering some big plays, on the positive side it intercepted three passes and delivered five sacks for a net loss of 27 yards.

The trip to Oxford turned out to be one of the more successful ventures for the Longhorns, and their fans. UT’s allotment of 3,800 tickets went quickly, but Texas fans seemed to manage about a quarter (estimated 15,000) of the 60,000 seats in Vaught-Hemingway Stadium.

In the world of track and field, where Marquise Goodwin became an international star this summer, there is a classification of excellence called “personal best.” The senior continues to blossom as arguably the best two-sport athlete in the college game.

Sharing the spotlight on Saturday, however, was a poignant trip for Mike Davis. There is something that we all celebrate about “come backs.” For a college football player such as Mike, it is particularly gratifying to watch. Life is, after all, a series of passages. We all face our personal demons daily. In Oxford, one of the wonderful things about their football experience is the place they call “The Grove.” There, thousands come, share their food and drink with friends and opponents alike.

And the lasting testament to The Grove is whatever happens this week, next week is a new beginning.

So let it be for Mike Davis. It is a true story, though shared infrequently over the last year, that his mother really did give him a middle name of “Magic.”

Saturday night in Oxford, Mike Davis came out to play. And for him and his Texas football teammates, the Magic was back.

05.28.2012 | Football

10.15.2010 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Dancing with the stars

Oct. 15, 2010

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

LINCOLN, NE – The somewhat curious relationship between Texas and Nebraska, when it comes to sports, has been kind of like one of those popular television shows where a couple of high profile folks get together and dance. And then, they go away.

Long before the two schools met after the creation of the Big 12 Conference, Texas and Nebraska shared a unique kinship. And those who think that this is the first time Nebraska’s been rankled at Texas in sports matters need a history lesson.

Fact is, the excellence in football the two schools have enjoyed began with the same guy. His name was D. X. Bible. After his success at Texas A&M in the early 1920s, Bible was hired as the Cornhuskers’ head coach in 1929 for the rare sum of $10,000 annually. In eight years his teams posted a record of 50-15-7. They won six conference championships. In the days when an all-American team consisted of eleven players annually, Bible’s team had four men so honored. Thirty-five players made all-conference. One of his victories had been a 26-0 win over Texas in Lincoln in 1933–which still stands as the Cornhuskers’ only home win against the Longhorns.

Then, following the 1936 season, The University of Texas offered Bible the unheard of sum of $14,000 per year to come to Austin as head football coach and athletics director. When he accepted the job, it was a big deal in Texas where he was making more money that the school president and not much less than the governor. But in the middle of the Great Depression in Nebraska, the move really rattled the coffee cups at the local breakfast spots. It was a heist, they felt, greater than The Great Train Robbery.

“They were furious,” recalls Bill Sansing, whom Bible hired as Texas’ first Sports Information Director in 1946. “They didn’t want him to leave, and they were angry that Texas had paid him 40 percent more than he was making there.”

Bible’s ten year tenure as Texas’ head coach established the Longhorns as a factor on the college football landscape. Despite an economy devastated by the Depression and a country immersed in the ravages of World War II, Bible’s teams won 63 games in his ten seasons. He took the Longhorns to their first bowl games and established “The Bible Plan” which placed emphasis on education as well as success on the playing field.

With 200 victories, he was the third-winningest coach in the history of the game when he retired after 33 years as a head coach following the 1946 season. He trailed only Amos Alonzo Stagg, who coached for 57 years, and Pop Warner, who coached for 44 seasons. He is in both Nebraska’s Hall of Fame and Texas’ Hall of Honor, and was inducted into the National Football Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 1951.

A token home-and-home series in 1959 and 1960, and a Cotton Bowl match following the 1973 season marked the only encounters between the two schools in football over the sixty years from the time Bible left until the start of the Big 12. Otherwise, it was out-of-sight, out-of-mind. In fact, when a Nebraska media member called asking about a possible reunion of the 1970 National Championship teams, it took a lot of Lone Star research for folks at Texas to realize that the Cornhuskers had been awarded the AP National Championship trophy after Texas had won the Coaches’ UPI Trophy prior to ending their 30-game winning streak with a loss to Notre Dame in the 1971 Cotton Bowl Classic.

What did happen along the way, however, was a love affair for Texas Longhorn baseball with Omaha, the site of the College World Series. As the Longhorns made what seemed to be annual treks to the city on the banks of the Missouri River, Texas fans gained a great appreciation for Nebraska and its people.

In the 1990s, as college football began the first of what would be numerous seismic shifts in conference affiliations, both the Southwest Conference and the Big Eight Conference reached a crisis. An economy once driven by ticket sales and donations now came to rely heavily on the medium of television. And the Southwest Conference and the Big Eight had only about seven percent of America’s TV sets each. At that point, the Big Eight didn’t even have a regional television package.

Penn State had started the tremors by joining the Big Ten. Arkansas left for the Southeastern Conference, thinking that Texas and maybe Texas A&M wouldn’t be far behind. After a summer of courting from other leagues, the issue was settled when the Big Eight and the Southwest Conference both dissolved. The eight members of the Big Eight, and four members of the Southwest–Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Baylor–united under the banner of the Big 12.

When the league was split into two divisions of six teams each, the North–with Nebraska and Colorado as the recognized national powers–was thought to be the stronger of the two. All of that changed, however, when Texas beat Nebraska in the first Big 12 Championship game in 1996, and Texas A&M knocked off nationally ranked No. 2 Kansas State in 1998.

From the start, there was a clear difference of opinion on some of the policies that were divergent in the two camps. Ages-old allegiances emerged in league voting, and invariably, it seemed Texas and Nebraska would find themselves on opposite sides of the boardroom.

Still, the tremendous class of the Nebraska fan base was never affected by that. When Texas won that first game in the TWA Dome in St. Louis, respectful Cornhusker fans–who had just seen their hopes of playing for a national championship dashed–congratulated the several hundred Texas fans who had joined them in a full stadium.

In 1998, when Mack Brown‘s first Longhorn team shocked Nebraska, 20-16, in Lincoln, the fans applauded Ricky Williams’ performance and actually began a chant of “Heisman” for him after the game. The next season, a turnover plagued Nebraska team lost a stunner in Austin to Texas, but returned the favor with a dominant win in the Big 12 Championship game.

It was in that setting that Mack Brown talked about “the neighborhood” of national football powers. He paid respect to Nebraska as the premier team of the 1990s in this part of America, and said his Longhorns were “just visiting the neighborhood.” The goal, he had said, was to buy a house there.

No one could have predicted that the Cornhusker win in that championship game in San Antonio would be the only one for Nebraska in the first ten years of Brown’s time at Texas. Then, of course, came the 2009 Big 12 Championship game in Dallas, where Texas’ Hunter Lawrence kicked a last second field goal for a 13-12 Longhorn win that sent them to the national championship game in Pasadena.

All of that, of course, sets the scene for what appears to be the last game between the two schools in the foreseeable future. With Nebraska headed to the Big Ten after this season, the likelihood of the two ever meeting again in the regular season seems remote. That, of course, remains to be seen. The two did play in 1933, and again in 1959 and 1960, so one should never say “never.”

What we do know is that Memorial Stadium in Lincoln will be filled with a sea of red, and a sea of emotion. It is doubtful that many remember being chapped about Mr. Bible leaving, but the story does set the tone, indicating that frustration goes back a long, long way with a very proud fan base. More prominent, of course, is the desire for revenge for last December, and you can throw in the fact that the Horns have won seven of eight under Brown, and eight of nine in the history of the league.

It is important, though, to let this final dance be a little more than that. These two football giants are two of the winningest programs in the history of the college game. Both schools are steeped in tradition and swelling with pride. The two states patriotically stand for all that is right about America. Somewhere, in the voices of the past, you can hear the ghosts of the game speaking into an old stick microphone and talking about the “color and pageantry” of college football. Yet, this game this day will be decided by the young, who play the game not for history, but because it is a game to be played in their lives, in their time.

Because, in the end, that is what this is really all about.

05.12.2009 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The end of the game

· May 12, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

If life is a game — and the angels that Bud Shrake thought talked to him would tell you that it is — then, as he said, “It must have an end.”

They buried Bud Shrake Tuesday, underneath the huge live oak trees which provided the shade that allowed a surprisingly gentle, cool breeze to touch his friends who had gathered there at the Texas State Cemetery. The marker of his late, great friend — former Gov. Ann Richards — was nearby.

The learned and the legends were there, from fellow writers who were in awe of his work to sports figures who represented but a few of the hundreds of subjects he would cover in a career which he began as a sports writer more than 50 years ago.

And that really is where our story begins.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, before the NFL became such a factor, college football dominated the national sports coverage in the fall. It was that era that produced not only the stars who would become famous, but the writers who would make them darned close to immortal.

Those of us who were young journalists would spend our time trying to emulate those writers as we wrote for our school papers and tried to find ourselves in our quests to become the next great American scribe.

It was a time when Darrell Royal’s Longhorns were the talk of college football, and every single orange-blooded fan would know the outcome of our Saturday’s heroes. But it was also a time when we would wake up early on a Sunday morning and grab the Dallas Times Herald or the Houston Post to see what Blackie Sherrod or Mickey Herskowitz had to say about it.

Blackie was the king, not only as a sportswriter, but as the leader of a group of writers who understood that writing was a gift, a present to be used for a positive presence. Dan Jenkins and Shrake were part of that group, and they soon were whisked away to New York to a fledgling new sports magazine called Sports Illustrated. Bud’s last year with a Texas newspaper came with the Dallas News in 1963 — when the Longhorns won their first National Championship in football. Gary Cartwright, who was tutored by Sherrod, Jenkins and Shrake, soon would become part of a unique literary society, which had its roots in sports writing, but would gain its fame in other venues.

Working with these guys in their ventures into the college football world were a equally unique group of sports publicity men which included Jones Ramsey at Texas, Jim Brock at TCU and Wilbur Evans, who split time between Texas, the Southwest Conference and the Cotton Bowl. They worked for their universities, and with the media.

The common bond between them all was that they genuinely liked and trusted each other. They worked together, socialized together, and together they chronicled moments and memories that would last a lifetime. They didn’t try to make the news; they tried to use the gifts they had been given to tell the story that would be the news in the next day’s newspaper.

For Shrake, that gift of writing carried far beyond the boundaries of the sidelines, the courts, the boxing ring or the retaining ropes at a golf tournament. He became a superb author, screenwriter, playwright, journalist, and — most of all — friend. And he possessed that rarest of all qualities — integrity. Once a hard liquor drinker with the best of them, he quit in 1987 and wrote what many believe to be one of his best novels, “Night Never Falls,” just to prove he could write without the kind of stimulants that made guys like Hemingway famous.

When the audience, which had packed the funeral chapel for Shrake’s service, was asked to use one word to describe him, the one that came to mind for me was “supportive.” He was always willing to offer advice, always willing to serve somebody else.

Fortunately for Bud, that trait rewarded him in the most unexpected way. When his love for golf and for an aging old pro at Austin Country Club named Harvey Penick prompted him to suggest that he team with Penick for an instruction book based on Penick’s years of notes, the project became, “The Little Red Book,” which became the biggest-selling sports book of all time.

The success brought him fortune, but he always deflected the fame to Harvey.

In a way, it wasn’t “who he was” that brought the elite to that funeral Tuesday, it was more about “what he had done for others.” But that, more than anything defined “who he was.”

Those who study such things will tell you that his books and his plays are as good as any ever written, but when Ray Benson, Jerry Jeff Walker and Willie Nelson sing at your funeral and sports figures like Darrell Royal, Ben Crenshaw and Barry Switzer mix with literary giants and those who would like to be, you know you had to be somebody really special.

Bud was not a religious man as some might define the genre, but he was a person of the spirit. He believed in angels, and he celebrated people and creatures, and sometimes those were interchangeable. And he believed that to be a game — any kind of game — it must have an end.

Was it yesterday, or was it nearly 20 years ago?

It was the Cotton Bowl dinner dance on Jan. 31, 1990, and there was Bud, dressed in his tuxedo and dancing with his companion, the new Texas governor Ann Richards, and there was Dan Jenkins and his wife June, with Dan laughing as he remembered the old days at the Cotton Bowl Ball, when they were part of the media, who were just happy to be at tables at the back of the ballroom.

Before her election, Ann, as State Treasurer, had been a regular visitor to Texas women’s basketball games, sitting courtside with Bud and former congresswoman Barbara Jordan. Bud asked me that night if he and the Governor could come and sit courtside at the men’s games.

“Well,” I told him, “we have a firm policy that only working press sits courtside at our men’s games, so I don’t think I can make an exception, even for a governor.”

And then I quickly added, “However, I will be happy to have you as a famous sportswriter, and you can bring a guest if you want.”

So the tall (he was 6-6) Bud and snow-white haired Ann became regulars, sitting with the “working press” when the media tables ran the length of the court, and they would dance together as partners for 17 years before her death in 2006.

In the shade of the oaks on a postcard kind of moment at the picturesque setting at the cemetery, Darrell Royal and Dan Jenkins were soon joined by Dan’s daughter, Sally, who long ago joined the ranks of the truly outstanding writers of our time. Turk Pipkin, the famous writer and actor, talked with Ben Crenshaw about Bud’s last round of golf, and how he parred the final hole he ever played.

In his time, Bud had written about sports legends and fictional characters who came to life in his many novels, plays, and screenplays.

Those of us who are fortunate enough to live out our dreams telling stories cherish those who tell them well, and nobody did it better than Bud. But his willingness to help those who follow will always be his best legacy. To those searching, he often said, “The difference between the right word and the almost-right word is the difference between lightning, and a lightning bug.”

In 2001, when Bud was hospitalized with a serious infection, I took him a copy of One Heartbeat, the book I had just finished with Mack Brown. When he got out of the hospital, he wrote me a note, thanking me, and congratulating us for a good book. “It will have a long shelf life,” he said, meaning that the book, and its message, would be enduring. It was typical of Bud, who was always willing to encourage.

In a sense, Bud’s passing is part of the ever-nearing twilight of an era in the world of sports, but even as those days close, his greatest story is his own — of the life he lived.

The game had come to an end for Bud last Friday, cradled in the arms of one of his sons.

At the funeral home Tuesday, a lot of powerful things were said that defined Bud, but they also reflected life. Perhaps the most powerful came from Pipkin, who said this: “You woke up this morning knowing who you were. Now go out and find who you can become.”

10.14.2012 | Football

06.08.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little Commentary: The tie that binds

The Texas Baseball team, on a journey which has taken unexpected twists and turns, extended its odyssey with back-to-back victories over Houston sending the Longhorns back to the NCAA College World Series for their record-extending 35th time.

Our friend Mr. Webster gives us a lot of choices to define the word “bond.”

It is anything that holds things together; It is a moral obligation; It is a vow or a promise; it is a wall, laid, brick by brick, with each strengthening the other; It is a security guarantee; a guarantee to make good on a commitment.

Augie Garrido would tell you it is the 2014 Texas Longhorn baseball team.

A journey which has taken unexpected twists and turns on the road to Omaha extended its odyssey with back to back victories over an excellent Houston team at UFCU Disch-Falk Field in the NCAA Super Regional, taking the Longhorns back to the NCAA College World Series for their record-extending 35th time.

And while much of the credit certainly goes to Garrido—the winningest coach in the history of the college game—and his staff, he is quick to redirect the responsibility for the season’s success to the players. And it is there that he sees the power of the word “bond.”

“The biggest challenge has already been accomplished by this team,” he said. “Not the winning, but the bonding that has taken place. That’s not going to break. That’s not going to go away. We have seen that from their response over three or four of the toughest weeks we have had. That bond has solidified in the minds of the players that they needed to take ownership of the team. The words that people use a lot about this generation of players are “not responsible and not accountable.” These players are responsible, and they are accountable for motivating and inspiring each other.

“They took the coaches out of that job, and that is when it really works.”

Great coaches are measured, as you have heard before, not by what they know, but by what their players have learned. That is why, over and over again, you will hear former Longhorn players talking about buying into Garrido’s “program and its process.”

The season had begun over a Valentine’s Day weekend under the stately spires of the historic Claremont Hotel in Berkeley, Calif., where the grand old structure opened its wide hallways to a team of a handful of veterans who were joined by a bunch of fresh-faced newcomers. Four games against the University of California had started this band of brothers on what would turn out to be a series of long journeys.

You learn a lot about each other when you live with each other, and this Texas team spent more miles traveling than any team in school history. With the bulk of the miles logged on the trip to Berkeley and Big 12 road trips to Morgantown, West Virginia and Manhattan, Kansas, the 2014 squad has officially gone 10,244 miles (according to Mapquest) together. And it would have been more had they not included the Big 12 Tourney in Oklahoma City on the road home from Kansas State.

It is ironic, then, that arguably their most important trip—to the NCAA Super Regional Tournament—required only a drive across town to UFCU Disch-Falk Field.

The schedule had matched Texas against some of the nation’s best baseball teams. When critics pointed to a rough home record, it should be noted that among those losses were games to TCU, Oklahoma State, Kansas, and Rice—all of whom were, at a minimum, NCAA Regional participants. The Big 12 itself was rated as the second best league in the country, and the fact that four Big 12 teams hosted NCAA Super Regionals bore that out.

Much credit has been given to the seniors, and to the leadership of Mark Payton and Nathan Thornhill. In his closing interview following the 2013 season after beating TCU in the ‘Horns final game of the year, Thornhill talked about the future for a 2014 Texas team, but he did it in the abstract. It seemed then that he wouldn’t be a part, choosing instead to head to professional baseball.

But in the midst of a long, hot summer, Payton and Thornhill weighed the value of another year at UT against a lifetime that would begin in minor league baseball. Both chose to return, and the nucleus was beginning to form. A recruiting class that included junior college transfer Lukas Schiraldi and freshmen such as Morgan Cooper, Zane Gurwitz, Tres Berrera and Kacy Clemens, among others, were rookies on that trip to Berkeley, but would each become important as the season progressed. As the team built itself with a healthy dose of history and tradition, it dedicated its season to the memory of former Longhorn great James Street, who died unexpectedly in September. For three of the newcomers—Schiraldi, Clemens and Gurwitz—the roots of UT’s long athletic legacy ran deep. Each was the son, or grandson, of a former Longhorn great.

The middle infield of C. J. Hinojosa and Brooks Marlow was steady throughout. A blossoming junior in Colin Shaw and the extraordinarily talented Ben Johnson joined Payton as part of perhaps the fastest outfield in school history. The final piece offensively came from senior designated hitter Madison Carter, who patiently waited his turn before coming up with a clutch hit in an extra inning win in Lubbock and went on to lead the team in batting.

The pitching staff rode the arms of Parker French, Dillon Peters, Thornhill and Schiraldi as starters, and got regular help from Cooper, John Curtiss, Travis Duke, Chad Hollingsworth, and Ty Culbreth.

Most of all, it was a team—as Garrido described it—of exceptional accountability. When Peters went down with an arm injury, Hollingsworth stepped into the breach and pitched the ‘Horns to victory in the NCAA Regionals in Houston. Up and down the lineup, over and over again, somebody different seemed to come through with a key hit or a great defensive play just at the right time.

There is no way to measure the value of Payton, who has played the game because he loves it, sharing it with teammates who have entwined themselves in each other’s souls. For 101 straight games through the Super Regional, Payton had reached base either by a hit, a walk, or by being hit by a pitch. It is a Big 12 record, and may even be the best ever in the NCAA—at least until somebody comes up with something better.

But this Texas team has been more than just what it has done at the plate, on the mound, or in the field. It has been the result of that bond which has transcended those on the playing field to those on the bench. And it has been a model of excellence in the classroom and in the community as well.

Mack Brown challenged his 2005 Longhorn football team just before its first practice for the National Championship game in the Rose Bowl to “find something you can do to help this team win.” That is exactly what Garrido told his baseball team, and the guys on the bench, some of whom have not even gotten into a game, have taken that to heart. In the good times and the hard times, they have been there for one another.

Both of the victories in the Super Regional, which were cheered on a home crowd decidedly burnt orange of 7,500 or so, turned out to be a showcase of the growth of the team from a tentative beginning in Berkeley to a seasoned team that looks like a national contender as it heads to Omaha.

Just when some fans and the media were questioning their ability to finish, Texas is playing its best baseball. Oh, they have lost some games and some teammates to injury along the way, but the drive, and the burning desire to succeed, is both rare and real.

In a press conference during the Super Regional, a reporter asked one of the players if they had “envisioned” this finish during their grueling fall workouts where, to a person, they were asked to commit to a common cause of returning Texas to the national college baseball landscape.

Webster tells us that “envision” is a transitive verb best defined as “imagine as a future possibility.”

On the other hand, the Oxford dictionary defines another word which is “something good which you hope you will have or achieve in the future.”

And that, it says, is the subtle difference between “envision”…and “dream.” And a dream is a state of hope, bound together by camaraderie and commitment, on the road to Omaha.