Bill Little Articles part IV

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

The night they all danced,-Texas and West Virgina

-

Football Bill Little commentary: The rest of the mail route

-

Football

Bill Little commentary: The victory lap

-

Welcome to the Big 12

-

Just Do It

-

Staying on the Horse

-

Coaches Coaching Coaches

-

The Night they all Danced

-

Following the Path

-

New Folks

Below are parts of some of his commentaries that discuss the value of sports in developing character through the process of team, learning from winning and losing, and epiphany moments for young athletes.

A celebration of all that is right about college sports- The night they all danced- Texas and West Virginia.

10.07.2012 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The night they all danced

But for those who experienced the amazing crowd reaction and the quality of play by both teams, Saturday night should underscore the very best qualities of college football. In the state of Texas, college football is nigh onto a religion, and we worship it because it can exhilarate and depress – both at the same time. It is the perfect teamwork example that sport imitates life – a game played by imperfect young people who are pieces of adults.

It is perhaps easier to do that when you win, and it is certainly not fun to lose, but in the grand scheme of things, it is important to remember that this is a game played by young people. They “get it” because they love to play. They are glad when they win and sad when they lose. Most of all, however, it is the joy of the competition which motivates them, moves them, and makes them jump.

10.19.2012 | Football Bill Little commentary: The rest of the mail route

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In Texas football, all losses are painful. Lose in the closing seconds, and you always wonder about the might-have-been. Lose big, and you are embarrassed. The great thing about games, and the great thing about life, is that whatever happens, there are two givens. One is that you cannot change the outcome, and the second is, we have a God-given right to try the game again.

I have said this before, and you will likely hear it again if you hang around long enough, but my memory of my brother’s high school graduation was a guest speaker who quoted the poem which says,

“Isn’t it strange that princes and kings and those who caper in circus rings and common folks like you or me Are builders of eternity? Each is given a book of rules, a pair of hands, and a set of tools. And each must build, ere his time is flown, a stumbling block, or a stepping stone.” In other words, it is not where you have been, but where will you decide to go? Folks are waiting for you down the road.

11.18.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The victory lap

·Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It has always seemed fitting that Senior Day and the game where they honor the newest members of the men’s and women’s Longhorn Halls of Honor usually occur on the same weekend. Because each is about accomplishment, each is about memories.

David Thomas, the stellar tight end who was part of the 2005 National Championship team, spent a little time with the current Longhorn team Thursday, and shared his memories of his Senior Day that season.

“Ahmad Hall and I looked at each other as we were finishing the “Eyes of Texas” after the game, and decided to take a victory lap around the stadium. All of the fans were still there, and I remember slapping hands with them all the way around the stadium. It is a day you never forget,” he said.

Can it really be that Blake Gideon, the son of a coach and a heroic mother-cancer survivor, will be leaving after starting every game of his college career? We have all come to know, not only the players, but their folks as well. We’ve learned of the social work in foreign lands of Dr. and Mrs. Acho, just as we have celebrated their sons, Emmanuel and Sam, as the ultimate student-athletes, on and off the field. Fozzy Whitaker’s mom is a hero for us for rearing a son after his dad died when he was young and loaning us that son as a champion and a heart-warming story in our lives.

It was Dr. Tucker, one of Austin’s premier cardiologists, who came out of the stands when Justin was in high school to help save Matt Nader’s life on the playing field. Folks called it a miracle, and we are told that is what happens when The Higher Power uses the hands and the knowledge of His creatures here below to do something extraordinary.

Miracles also unite those gifted hands with the power of an individual’s will, which brings us to Blaine Irby. We watched him come from California and watched his wonderful parents transition from loved ones who anticipated one career beyond college for their son to a vigil that he would, in time, walk normally. The doctors and rehabilitation specialists will tell you that Blaine Irby is a miracle, and in that space, we marvel, and we celebrate.

Fifteen members of this senior class have played in a combined 567 games, with 217 stars. Besides Blake, Justin, Fozzy, Emmanuel, and Blaine, they include Cody Johnson (who unselfishly moved to fullback this year), David Snow (who has played center, guard, and tackle in the offensive line), Tray Allen, Kheeston Randall, Keenan Robinson, and Christian Scott.

Others who have contributed significantly include deep snapper Alex Zumberge*, fullback Jamison Berryhill, Mark Buchanan, Ahmad Howard, John Paul Floyd, Luciano Martinez, Patrick McNamara, John Osborn, Sam Walker, Trey Wier* and Nick Zajicek.

In all of the years of the men’s Longhorn Hall of Honor inductions, dating back to 1957, only one Longhorn, who neither played or even attended UT whose only participation has been as an assistant coach, has ever been inducted. That person was Darrell Royal’s right-hand man and defensive guru, the late Mike Campbell. Mike last coached at Texas in 1976, and he died in 1998. So how do the lives of two men, the swimmer Kris Kubik and the football coach Mike Campbell intertwine?

Those whom we honor Saturday night will never pass this way in this same setting again. But they return (in the case of the Hall of Honor inductees), or they leave with their memories and their legacy. And that, after all, is their gift to us.

Bill Little commentary: Welcome to the new Big 12

Oct. 14, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It’s not like we didn’t tell you this was coming. College football, particularly in the Big 12 Conference has changed, and nobody, not the coaches, the players, the fans or the media have an immediate answer to what is happening. Week to week, fans are outraged, the media is stunned, and the teams and coaches are mad and frustrated.

Saturday’s America in the Big 12 was the most cryptic example to date. Three weeks ago, some writers were forecasting Oklahoma’s doom. One long-time pundit actually predicted the Sooners would go 6-6. In Lubbock, folks were ready to cry for the head of Texas Tech coach Tommy Tuberville. Baylor was the next hottest thing on the turf, second only to West Virginia, which it was said might be the best team in the country. TCU was written off after losing their starting quarterback on disciplinary issues. Kansas couldn’t beat anybody and Oklahoma State was a couple of seconds away from being unbeaten. Kansas State was set to roll through the league after whipping Oklahoma in Norman, and Iowa State was merely an afterthought following a loss to lightly regarded Texas Tech, and Texas was coming on strong after splitting scoreboard shootouts with Oklahoma State and West Virginia.

Then comes Saturday, and the first full weekend of league play. Texas Tech knocks West Virginia out of the top five, 49-14. Oklahoma beats Texas, 63-21. Oklahoma State survives Kansas, 20-14. Kansas State has to come from behind to beat Iowa State, 27-21. And TCU goes into Waco and hammers Baylor, 49-21.

So get used to it. Welcome to the new Big 12.

What the league fathers have done with this collection of teams from the middle part of America plus West Virginia, is to put together the most unpredictable league in the country. Just when you think you have it figured it out, you don’t.

The only constant in the weekend is that the Texas-Oklahoma game, AKA the AT&T Red River Rivalry, is (unfortunately for Texas right now) following an historic pattern that reflects a series which goes in streaks.

Starting more than 70 years ago, D. X. Bible and his Texas Longhorns started it by winning eight straight games over the Sooners from 1940 through 1947. Bud Wilkinson and his Oklahoma team followed that by going 9-1 against Texas from 1948 through 1957. Then, Darrell Royal secured the edge for Texas as his Longhorns put together the series’ most dominant string, going 12-1 from 1958 through 1970.

The pendulum swung in the early part of the seventies, when Oklahoma won five before the 6-6 tie in 1976 ended that run. Fred Akers achieved early success, putting together a 4-1-1 streak from 1977-84. Oklahoma countered with a 4-0 string from 1985 through 1988. Then David McWilliams and John Mackovic combined to lead their teams to a 5-1-1 mark from 1989 through 1995. Texas stretched the overall run to 8-2-1 by going 3-1 to close out the last decade of the 20th century and open the Mack Brown era with back to back wins in 1998 and 1999. The 2000s have found OU with a five game streak to start the decade, before Texas won three of the next four. Now OU has won three straight.

Mack Brown was the first to acknowledge that the Longhorns’ performance in the game Saturday was unacceptable by any standard. What makes it even more puzzling is that there was no way to anticipate its coming. The defensive coaches have been scrambling all season to pull together a unit that came into the season very young, and has been hit by critical injuries. Fourteen sophomores and freshmen were on the two-deep for the Oklahoma game. Mack praised the play of seniors Alex Okafor and Kenny Vaccaro on Saturday, but Okafor’s book end on the other side at defensive end, Jackson Jeffcoat went out with injury. Jordan Hicks, a junior who is the most experienced linebacker, hasn’t played in two games because of injury.

Having worked for two years in Oklahoma City with The Associated Press, I can tell you that the Oklahoma nation traditionally approaches this game with more intensity than our folks south of the Red River. Again, that is a given, year after year.

An expression I heard a long time ago from a coach often serves well as you bounce back from a loss like Saturday’s. Somebody asked him to break down the debacle he had just seen publicly.

“It serves no purpose,” he said. And he was right. A learned oilman once was told that one of his workers had inadvertently run over and broken a well-head in West Texas.

“I am going to fire that guy,” said the foreman. “No,” replied the oil man. “You’re not going to fire him, because he is the only guy in the company who knows where that well-head is.”

In the locker room following Mack Brown‘s comments, players spoke emotionally and defiantly, not about what had happened, but about the future of this team.

Games like Saturday are a reminder that sport teaches lessons of life, and life, conversely, teaches lessons in sport. In a league where everybody plays everybody, there is a bunch of business – a combination of challenges and opportunities – remaining in this season.

As a kid, I was a great fan of poetry, and one of the most interesting was a poem by an author named Edmond Vance Cooke. It was entitled, “How Did You Die?”

A significant, and applicable-at-this-time verse reads, “You are beaten to earth? Well,well, what’s that? Come up with a smiling face. It is nothing against you to fall down flat – but to lie there, that’s disgrace.”

Edmond Vance Cooke certainly never heard of the Texas-Oklahoma game, nor the Big 12. But his challenge – to fight back – fits in any league, at any time, in any world.

10.21.2002 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The battle cry

Somebody started it, a single voice, as if a gentle breeze would become a strong wind across the plains.

“The pride and winning tradition of The University of Texas will not be entrusted to the weak or the timid. The Pride And Winning Tradition Of The University Of Texas Will Not Be Entrusted To The Weak Or The Timid. THE PRIDE AND WINNING TRADITION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS WILL NOT BE ENTRUSTED TO THE WEAK OR THE TIMID!”

They were shouting then and the locker room in the northeast corner of KSU Stadium resonated with the chant.

By the time head coach Mack Brown spoke emotionally to his team about tenacity and heart and proving something, if only to yourselves, the tension of the final moments of the 17-14 victory at No. 17 Kansas State had transformed to a very special joy.

“Remember this moment because you are the lucky ones,” he said. “Very few people get to experience this feeling that you have tonight.”

He wasn’t talking about victory, redemption or vindication. He was talking about that unique togetherness that only a band of brothers, or sisters, or any combination thereof, can feel when they bond as a team for one common purpose.

This was a Texas team which went to Manhattan, Kan., surrounded by a lot of detractors and doubters. The critics discounted their talent and completely underestimated their heart and resolve.

“It isn’t the fact that you get knocked down, but to lie there, that’s disgrace,” the poet said.

This was a team, challenged with injuries and bruised with bitter defeat, that absolutely and completely willed itself to get up and win.

A team, we have been told, is a collection of individuals who, in order to win, come together as one heartbeat. Saturday night in the plains town they like to call “The Little Apple,” a bunch of Longhorns did just that.

Make no mistake about it, this was a big game. Kansas State is an excellent football team and they have brought something tremendously special to the people who believe in them. Just as Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium has been transformed to a sea of orange, so it is that the people who don purple have engulfed and exuded pride in their Wildcats.

Everything, it seemed, pointed to a K-State victory. The odds-makers had established the 17th-ranked Wildcats as a two-point favorite over the No. 8 Longhorns. A season that has been scarred by an inordinate amount of injuries got even stranger when senior tight end and placement snapper Chad Stevens twisted a knee during Friday’s walk-through. All week, the Longhorns had planned to use a power running game, with a formation that included two tight ends, junior Brock Edwards and Stevens. With the loss of Stevens, half of the offensive game plan went out the window.

It is important to remember that this game mattered a whole lot to both of these teams. Kansas State entered the game with a Big 12 North Division loss to Colorado. Texas entered with a South loss to Oklahoma. Another league loss and one of the teams was going to be on the ropes with its chances to win the conference. Both had entered the season with hopes of winning not only the league, but all of their games.

Following the Longhorns’ final practice in Austin, where they took advantage of their new indoor facility with an artificial surface similar to the one at K-State, Brown sent the bulk of his team back to the team room for their traditional Thursday pregame meeting. He kept with him the seniors, those guys whose careers as college players were now down to six regular season games.

In the spacious cavern that is the new “bubble,” they talked alone. Earlier that day, the kickers had worked on the artificial surface. The hold, the spot, the measured steps and footing that can be different from grass had been explored.

Then, Friday morning, the team departed for Kansas.

For a handful, such as senior Beau Trahan, there were bad memories of KSU Stadium, for it was there in Brown’s first season, that the Wildcats had crushed the Longhorns, 48-7. That loss had come a week after a good UCLA team had beaten Texas in Los Angeles. The setup was the same. The results needed to be different. Brown spent a good 15 minutes, much longer than usual, talking to his team after Friday’s walk-through.

There is little more frustrating in football than a night game on the road. Coaches plan for them and everybody dreads them, but this season, the Longhorns have caught a break. Their night game routine, both home and away, has been the norm, rather than the exception. In fact, of their first seven games, the Horns have played four of them at night.

For 10 consecutive road games, not including the neutral site games such as the OU game in Dallas or the playoffs or bowl games, Texas had worked its road plan successfully. Not since the Stanford game, the first road trip of 2000, had the Longhorns lost on the road.

However, this time the odds were against them. No one connected with the program believed the Longhorns would not be emotionally ready for the game. That was about emotion. Logic said that ready or not, this was an excellent Kansas State team that would be hard to beat.

At that moment, emotion stepped up and hammered logic.

When it was over, it would be impossible to name the stars. You could talk about the defense, which bottled up the dangerous Ell Roberson and the offense, where senior QB Chris Simms had some wonderful throws and junior WR B.J. Johnson had one of his most significant games as a Longhorn, with four catches for 132 yards that either made or set up every score.

Mention a name on either side of the ball and on special teams and you’ll name a player who did his part to win.

Senior DE Cory Redding and sophomore LB Derrick Johnson led the Longhorns tacklers, but the others who saw action weren’t far behind.

Senior Brian Bradford punted exceptionally well and he and the cover guys limited a potent K-State return unit to only nine yards on two returns.

Sophomore PK Dusty Mangum booted the first game-winning field goal of his career and it came only weeks after he had been maligned and doubted. The measured steps and the work on the artificial turf in the new facility paid off.

However, the most impressive part of this college football game between two really good football teams was that nobody went down easily. Kansas State played tough defense, and at the end, when the game was on the line, the Wildcats made plays that put them in position to win, or at least to send the game to overtime.

With seven seconds left in the game came the play that will be forever known as “the block.” Elsewhere on this Web site, you can find Chris Carson’s classic photo of the play. It will show a leaping Jackson, sailing high despite a sore ankle. It will show junior DE Kalen Thornton reaching, and in the middle, there is junior DT Marcus Tubbs.

The Texas defensive line had moved the battle front. With their surge, they penetrated and annihilated the Wildcats line. Another angle shows a K-State lineman, desperately clutching the back of the jersey of Wright, who had pushed by him.

With his big left hand, Tubbs swatted the ball away. Celebration roared on the UT sidelines, across the field from the ball, which seemed to be trickling harmlessly away. In the midst of the joy, assistant coach Mac McWhorter and others were still engaged in the battle.

“Get on the ball,” McWhorter shouted.

With one tick left on the clock, junior CB Nathan Vasher did.

It was one more moment where team figured into the win.

You see, it was third down. Had K-State recovered the ball with time remaining, they could have tried again.

The late trainer Frank Medina had a sign in his training room in the old Longhorns locker room under the graying Memorial Stadium stands and it was there until Texas moved into the football complex at the south end of the field in 1986. A similar sign has hung for years in the Texas baseball locker room at Disch Falk Field.

When they remodeled the facility that is now known as Moncrief-Neuhaus, Jeff Madden changed the wording just a little and posted it in huge letters at the south end of the strength and conditioning room.

It reads, “the pride and winning tradition of The University of Texas will not be entrusted to the weak or the timid.”

On Saturday night in Manhattan, it wasn’t.

Bill Little commentary: Looking back

Integrating athletics at The University of Texas at Austin.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In celebration of Black History Month 2014, it is appropriate we take a look back at the journey as far as University of Texas athletics is concerned.

For reference, the most significant events came 50 years ago in the 1960s, when the UT Board of Regents cleared the way for black athletes to participate in varsity sports at The University.

The pathfinder from that era was James Means, an Austin native and high school track athlete. Means enrolled as a student at UT in spring 1964 when the Southwest Conference, as well as UT, took an affirmative step to allow participation in athletics for all eligible students.

On Feb. 29, 1964, Means participated in a track meet at Texas A&M as a member of the UT Freshman team — in the days before freshmen were eligible to participate with the varsity. In 1965, he became the first black athlete in the Southwest Conference to earn a letter. He went on earn three letters at Texas before graduating in 1967.

About the same time, a young man named John Harvey was etching his name in Austin history as perhaps the greatest athlete ever at the original Anderson High School. Anderson had remained an all-black school on the east side even though Austin’s schools had technically been integrated since the mid-1950s.

Harvey actually signed a letter of intent to play football at Texas for Darrell Royal. He never entered UT, choosing instead to go to Tyler Junior College, where he became an All-American and later a star in the Canadian Football League. In the fall of 1968, a linebacker from Killeen named Leon O’Neal became UT’s first black football recruit to participate, playing as a freshman.

O’Neal had left school by the time Julius Whittier signed and enrolled as a freshman in 1969. Whittier, who was inducted into the Longhorn Men’s Hall of Honor last fall, lettered in the seasons of 1970 through 1972.

Other pioneers included Sam Bradley, who was the first black men’s basketball letterwinner in 1970, and Andre Robertson, who lettered in baseball as a freshman in 1977 — before going on to a career that included starting shortstop for the New York Yankees.

Royal made a strong statement in 1972 when he chose Alvin Matthews, a NFL star with Austin roots, as the first black assistant coach at Texas. Matthews, who was playing for Green Bay at the time, had been a star at Texas A&I (now Texas A&M-Kingsville), and was a product of Austin High.

Matthews served dual duty for two years, spending time at Texas in the off-season and reporting to Green Bay, until it became clear that his success in the NFL would keep him in the league longer than anticipated, and he gave up the Texas job.

The first black head coach at Texas was Rod Page, who led the UT women’s basketball team to almost 40 wins in two seasons in 1975-76 and 1976-77 until turning the program over to Jody Conradt.

It has been 50 years since James Means changed the face of UT Athletics, but in truth, the powerful legacy of the contributions originally manifested itself more than 100 years ago.

Emerging from the early days of Texas Football was perhaps the most interesting character in The University’s young history, and he wasn’t even a player.

He would dress in a black suit, with a black Stetson hat, and he touched more football players — with his hands and with his heart — than any man in the first 20 years of Texas Athletics.

Henry Reeves was a special kind of pioneer. He was born April 12, 1871, in West Harper, Tenn. He was the son of freed slaves, a black man who would set forth to make his mark in a new world of freedom.

No one knows when he came to Texas, but he was a fixture in athletics almost from the beginning. He carried a medicine bag, a towel and a water bucket.

In fact, Henry Reeves became almost as well known as the team itself. The cries of “Time out for Texas!” and “Water, Henry!” brought the familiar sight of his tall, slender figure quickly moving onto the field. There he would kneel beside a fallen player, or patch a cut, or soothe a sore muscle.

“Doc Henry” he was, and in the 20-plus years from 1894 through 1915, he was a trainer, masseuse, and the closest thing to a doctor the fledgling football team ever knew.

In the 1914 publication “The Longhorn,” he was called “The most famous character connected with football in The University of Texas.”

“He likes the game of football, and loves the boys that play it,” they wrote.

But who was this man? Where did he get his knowledge? How did he earn acceptance and respect?

You can look at the pictures and see a mature, studious face — a man whose skills and understanding were obvious. It is likely, folks surmised years later, that Reeves had been trained as a doctor at some of the historically black colleges of the time, and had worked in segregated hospitals.

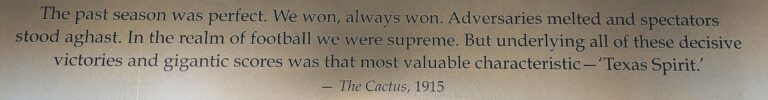

Once, a new athletics administrator tried to dismiss him and the students rose up in protest. Henry Reeves stayed on. The Cactus yearbook listed the all-time teams of the early days, and one team was picked by the coach, Dave Allerdice. The other was called “Henry’s Team.”

As the team boarded a train to go to College Station to play the Aggies in 1915, Doc Henry felt a numbness that all his self-taught medical knowledge couldn’t cure. He went on to the game, but by halftime the stroke that would kill him had paralyzed the lanky trainer so that he could no longer run.

Henry Reeves lingered for two months after the stroke, and the entire student body took up a collection to pay his medical bills. After his passing, the athletics council voted to award his widow a small pension.

When he died, the Houston Post gave him a special tribute. To put it into perspective, in that day, a black man could not attend The University of Texas, nor for that matter, eat at the same table with the men he treated.

“The news of his death will be heard with a sense of personal loss by every alumnus and former student of The University of Texas, whose connection with the institution lasted long enough for him to imbibe that spirit of association which a quarter century and more of existence has thrown around the graying walls of the college.

“No figure is more intimately connected with the reminiscences of college life, none, with the exception of a few aging members of the faculty, associated with The University itself for so long a period of time.

“In the hearts of Longhorn athletes and sympathizers, Doctor Henry can never be forgotten. A picture that will never fade is that of his long, rather ungainly figure flying across the football field with his coattails flapping in the breeze. In one hand he holds the precious pail of water, and in the other the little black valise whose contents have served as first aid to the injured to many a stricken athlete, laid out on the field of play.”

Henry Reeves left the young university a message it would take years to resolve.

It was a message that the color of a man’s skin made no difference in his mind, his skill, or his heart. All are given a chance to make of themselves what they choose.

They are the pioneers — whose legacy we celebrate — and whose memory we honor.

10.31.2010 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Just do it

Oct. 31, 2010

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Longhorns baseball coach Augie Garrido figured this out a long time ago. So did Nike.

Webster defines the word “try” as “to test; to attempt; to endeavor; to make effort.”

“If you set out to ‘try’ to do something,” says Garrido, “you’ll never get it done. Don’t ‘try’ to hit the ball, just hit the ball.” Nike’s slogan has become “Just Do It.”

I realize we are playing with words here, but Saturday night in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium may well have been a case of guys “trying” too hard. Wanting desperately to make a play, they got lost in the attempt and failed to achieve what they thought they were “trying” to do.

You can test this for yourself. Drop a piece of paper on the floor and “try” to pick it up. Your natural reaction is to reach down and grab hold of the paper. You didn’t “try” to do it, you just did it. If you simply “try,” it will just lay there. Good intentions are good, but that is kind of like what Darrell Royal once said; “Potential means you ain’t done it yet.”

It is both the most gratifying, and yet the most frustrating, part of coaching a team. You appreciate it when your team plays hard — when it “makes effort” if you will — and yet you are immensely disappointed when that effort does not translate into success. You can’t “try” to stop them; you “have” to stop them. You can’t “try” to score, you just score. And what happened Saturday night was that every Longhorn player wanted to win so badly that they let their “want to” get in the way of their “get to.” The result was a handful of big plays by Baylor, and too many dropped balls and penalties by Texas, that netted a 30-22 Baylor victory.

The frustrating irony for the Longhorns, who are now 2-3 in the very balanced Big 12 South, is that they have had a final chance on the last drive of the three losses to tie the game. Oklahoma won, 28-20. The Iowa State game finished at 28-21. And now Baylor stops a final drive for a 30-22 victory. When it has needed to get points inside the red zone, Texas has had to settle for field goals. Saturday, a remarkable Justin Tucker tied a UT school record with five field goals. Had two of those penetrations translated to touchdowns instead, the score would have been tied.

After a night when the Longhorns honored history by retiring Colt McCoy‘s jersey, the Longhorns of 2010 now need to celebrate the past, but also need to turn their attention forward. At 4-4, there is still a third of the regular season to play. Mack’s saying of “They will remember November” has never applied more than to this 2010 team. The media and the negative folks will dredge up all of the dire historical notes of what has happened so far, but what happens next is all that can be controlled right now. True enough, in time all that may be will be a line in the record book, but the November games against Kansas State, Oklahoma State, Florida Atlantic and Texas A&M will ultimately determine how this team is remembered.

Prior to this season, the Longhorns only losses in Big 12 regular season competition under Mack Brown had come to Oklahoma, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Kansas State. The Wildcats, in Manhattan, are the next team on the UT schedule.

When a reporter asked Mack Brown in the postgame press conference, “How do you fix this?”, his answer was simple. He didn’t talk about “trying.” He said instead, “You just keep working.”

I remember when I was with The Associated Press in Oklahoma City in 1967 and the Longhorns were in the midst of a season that would end at 6-4. I had called the home of Darrell and Edith Royal about 10:30 p.m. on a Sunday night to get a quote about Texas’ upcoming game with the unbeaten Sooners. Coach Royal wasn’t home.

“He’s at the office, Bill,” Edith had said. Then she paused. “They are having to coach a lot harder this year.”

The decade of 2000-09 for the Longhorns produced the most number of wins in a decade of any team in the history of college football. The decade was also the most successful, percentage-wise, of any ever at UT.

Several times on Saturday, the crowd of over 100,000 arrived at a place which respected that what was happening on the field was only a game. The first was the recognition of Colt, for all that he had meant. The second was the recognition of the significance of the players’ effort to call attention to the lives — including many of their own — affected by breast cancer. Each player and coach had dedicated their game to someone in their lives who had been touched by the disease.

Finally, the silence was incredible as Aaron Williams and Blake Gideon lay on the field after colliding near the end of the game. In that moment, it was no longer about a game, but about real people, and real lives.

It always is. Football at Texas has brought tremendous joy to hundreds of thousands of people over the last years. We respect that, and we treasure those moments. And players, coaches, and fans never expect that to change. But for fear of being philosophical here, it does. They call that life.

You keep working. You keep fighting. In the movie “Star Wars,” the Jedi Master Yoda put it another way: “Do or do not. There is no try.” I say again, and here repeat: a third of the season remains.

05.21.2009 | Baseball

Bill Little commentary: Staying on the horse

May 21, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

OKLAHOMA CITY — It is the legend of the rodeo, where the old-timers sit behind the loading gates and wait for the next ride, their hats stained with the sweat of many a failed excursion on a wild pony.

And this is what they say: “There never was a hoss couldn’t be rode and there never was a cowboy couldn’t be throw’d.”

Texas had opened the Phillips 66 Big 12 Baseball Tournament on Wednesday, and that lesson had come hard. Baylor, the eighth seed, had pounded arguably the nation’s best pitching staff in a 14-9 drubbing.

The “high and mighty” had come crashing to earth like a deflated airship.

And so it was that Thursday, when the Longhorns arrived at AT&T Bricktown Ballpark prior to their game against Kansas, Augie Garrido gathered his pitching staff for a lesson in humility. For 30 minutes, the coaches and the pitchers reviewed what had gone wrong on Wednesday.

The demise had come after Cole Green had pitched the Longhorns to a 7-3 lead over the Bears through five innings. Over the next four frames, the Bears, who had been frustrated by a late season slump, scored eleven runs and won handily. The Texas bullpen had been rocked.

“We talked about a lot of things,” Garrido said. “A lot of what happened had to do with the organization of the bullpen, and as hard as that game may have been, it shows us something that we needed to have fixed before we begin NCAA play next week.”

Ironically, it was Baylor coach Steve Smith who would offer the answer to the blue print the Longhorns would follow after their meeting.

“This Texas team,” he had said at Tuesday’s opening press conference, “may be the best `team’ I have seen in a long time. They play as a team, they work as a team, they pick each other up as a team.”

College baseball, 2009, is in an interesting place. As the Big 12 reflects, and the rest of the nation will confirm, there are a lot of “good” teams. Limited scholarships and the aggressiveness of professional baseball has changed the dimension of the college game. There are no teams filled with “great” players any more.

Even though the coaches at the press conference on Tuesday sang the praises of the players in the league, the truth is, destiny will likely not be kind to an abundance of the players who seek to play the game at the highest level in “The Show.”

The days of teams such as Augie’s 1995 Cal Fullerton team, the Southern Cal’s of the `70s, and the Arizona State’s and the Texas’s are but memories to the aged, now graying, folks who have followed the game for a long time.

An Omaha which would feature a Keith Moreland, a Fred Lynn, a Dave Winfield, a Barry Bonds, a Robin Ventura welcomes a new style of player who comes hoping to play at the next level. Those other guys expected to. An influx of foreign players, as well as a rough road through the minor leagues, has changed the Major Leagues as well.

That is why what happened on Thursday, and the validation of the spirit of this Texas team of 2009 is so important. As Mack Brown has preached, you have to be consistently good to be great. And you can have a great team that is made up of good players who play for their teammates, and for the love of the game.

Chance Ruffin knew that when he went to the mound on Thursday, clutching the baseball as the Longhorns’ starting pitcher assigned to set the world right again for his teammates.

“It had been Johnny Allstaff for us against Baylor,” he would say after hurling the `Horns to a 9-3 victory over the Jayhawks. “It was my job to give our guys some rest.”

The offensive side duplicated its nine-run output from the loss to Baylor, but Ruffin went the distance to earn the Longhorns’ first victory of the season over the Jayhawks, who had taken three one-run victories in Kansas at the beginning of the league season. Still, it was the combination — the “team,” if you will — that made all of the difference for the Longhorns on Thursday.

It was Michael Torres flashing consistency, going three for four, and it was Brandon Belt and Cameron Rupp connecting on two and three run homers, respectively. Ruffin threw perfect baseball through the first three innings, and by the time David Narodowski got the Jayhawks’ first hit on a solo homer in the fourth, the Longhorns held a comfortable 6-0 lead.

For the game, Ruffin threw 129 pitches and gave up four hits. He walked two and struck out six, and he got stellar defensive play behind him. Second baseman Travis Tucker turned in a phenomenal catch and throw, and senior shortstop David Hernandez went out and played left field, where he made a spectacular running catch.

The victory stretched the Longhorns’ season record to 39-13-1, and the win certainly will not be lost on the NCAA Baseball Committee as it begins its deliberations this weekend on regional seeding. It would appear that the Longhorns remain in good position for a top eight seed, meaning that they would host a regional and could host a Super Regional if they advance out of the regional.

In the pool play of the tournament, patterned after that used in most international competitions, Texas is 1-1 and will play Kansas State on Saturday. A victory in that game, regardless of its bearing of which teams gets to the Sunday Big 12 Tournament final, would give UT 40 wins and they would leave Oklahoma City with no fewer than two victories secured.

There have been times this season when this team has had a magical quality about it, a quality of class that seems particularly special.

The players will tell you that is because they have committed themselves to the concept of “team.” A year ago, they will tell you, they might not have bounced back in the Kansas game, or in any of the number of “must” wins which they achieved. That, they say, is the result of playing the game for each other, and playing the game for the fun of it.

That, after all, is what this game of ball and stick and glove began with so long ago for all of these “boys of summer.” And it is that attitude that nurtures the sometimes rare, and always precious, thing we call a team.

03.03.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Coaches coaching coaches

March 3, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

When Mack Brown walks out of his office during the next several days, he will be venturing into a time capsule, both from the past and destined for the future. It is one of the very special weekends of the year for him.

That is because Thursday, the 14th Annual Texas Longhorns High School Football Clinic begins, with over 400 high school coaches spending the better part of three days working and listening. The weekend also marks the first of two consecutive pilgrimages to Austin by high school teams, fans, and a plethora of coaches for the UIL State Girls and Boys basketball tournaments.

There are times in life when we function because of duty, and there are times when we function because of roots. The latter is the case for Mack when it comes to high school coaches. His story began, of course, as a youngster dressed in his tiny letter jacket, seated on the front seat riding a yellow school bus to the games of Putnam County High School, where his granddad, Eddie “Jelly” Watson, was the head football coach. It includes the heritage of Watson, who became the winningest high school coach in middle Tennessee. Mack’s dad also coached, and one of his role models growing up was his high school coach, Bucky Pitts. So the legacy, and the commitment to the profession, run deep.

I was reminded of all of this when I had a chance last fall to attend my Winters High School class reunion, and got to see W. T. Stapler, who was our high school coach. Stapler went on to become a legend in the high school ranks in Texas, and still watches as much football as he can, because he misses the game.

The trip also brought back memories of small town life, and it was good to see a new gymnasium—a multi-purpose facility—replacing what we knew as the “New Gym.” That one was built in 1954.

But as I sat with Coach Stapler (you never grow out of that title of respect) in the spruced-up football stadium and toured the new sports complex, I couldn’t help but think of what W. T. Stapler and Freddie Gardner had meant. In a way, this is the beginning of two weeks of tribute to folks like them.

The Mack Brown Clinic this year is particularly exciting, because it will feature the new Longhorn assistant coaches, as well as programs and a panel featuring state champions and currently successful high school coaches.

They, as well as W. T. and Freddie, represent what is good about sport—and they represent their fellow teachers at a time when frightening budget cuts threaten the fiber of our schools. That is because teachers teach, and coaches coach—not for the money or the fame—but because they care.

They are there, in the classroom and in the arena, to challenge young people to think…to solve problems…to achieve great things. Mack’s respect for high school coaches comes from his understanding that they, more than coaches at any level, labor with what they have. Where college coaches recruit and pro coaches draft, the high school coach gathers the young people of their community and proceeds to form a team.

W. T. Stapler was young when he coached in Winters—it was his first job. And I can’t remember the number of games that we won, but it wasn’t very many. I do remember that we mattered to him, and from his trek back to the old school fifty years later, we obviously still do.

Freddie Gardner mattered for the same reasons, although Freddie’s teams were actually more successful. What Freddie taught was about life. On Sundays, Freddie would sit about midway back at the edge of a pew at the Church of Christ, and the rest of Freddie’s life was about the kids and the sport. Her kids. Her sport. Freddie Gardner was the women’s basketball coach.

I caught up with Jody Conradt this week and asked her why, in small towns in Texas, the W. T. Staplers and the Freddie Gardners mattered.

“Because,” she said, “more than anything a young person can do, sport teaches life skills. It teaches you how to win and how to lose, how to interact with teammates, and how to carry yourself with class – win or lose. It teaches you the value of commitment, the importance of intensity, and the value of seeing things all the way through.”

I think what Jody said was, never give up.

When the high school coaches come, with their brightly colored warm-up suits, logo shirts and varied caps, they bring all of that to a common area to learn, to teach, and to exchange ideas.

At a time when the teaching profession is under a huge microscope, they come with a desire to learn, so that they can go back and help young people.

I am reminded of a moment almost 20 years ago now when we held a “Symposium on the Integrity of Sport” here in the spring of 1994. The University had invited journalists, professors, and a myriad of others to be a part of a panel discussing sports as we headed into The University’s second century of athletics competition.

One of the invitees was H. G. Bissinger, who had become famous for writing one book—the highly critical “Friday Night Lights”, where he assailed sports in general, and Texas high school football in particular. That book remains his greatest claim to fame.

Bissinger that day was seated at one end of the long table of panelists stretching across the LBJ Auditorium. He had seized the moment to rail against the evils of sport, and he was carrying on about the over emphasis of sport. That was when, from the other end of the table, the cavalry arrived. Or, better said, the “Voice of God” spoke. Barbara Jordan, the former congresswoman who had returned to teach at the LBJ School and had become an unabashed fan of Texas athletics, had heard enough. She slammed her hand down on the table, and the room stopped.

“Why does sport matter so much?” she boomed.

“It matters because sport is vital, it is viable, it is basic, and it is essential. Sport is not a frivolous distraction as one may first, without thinking, believe. Sport is an equal-opportunity teacher. It is a non-partisan event. It is universal in its application.

“I see sport as an antidote to some of the balkanization that we see occurring in our society; everybody wanting their own private little piece of turf; an absolute abandonment of any sense of common purpose, of common good. It is almost a cliché to say there is no “I” in the word “team.” If you are so focused on self, you cannot have any awareness of the common good.

“Another reason why I believe sport is essential is self-esteem. In order to be a contributor to American life, each individual needs to have a high regard for himself or herself first. Sport can do that. If you get out there and you have never been recognized for anything before in your life, if you show some capability, some particular tilt and talent for a sport, it gives you self-esteem.

“I believe that sport can teach lessons in ethics and values for our society. It is attractive to the young, and how many times have we heard someone despair over the plight of our young people. If you give them something to engage their energies, you would see that it might be something which lures them into the community of mankind and womankind.”

I figure Bissinger must duck every time he flies into Austin and walks by the statue in the Barbara Jordan Terminal.

Coaches, however, do not duck. They do what they do, work with what they have, and believe that through their sport, they can make a difference for young people. It is what they do. Teachers teach. Coaches coach. Because they care.

11.22.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The night they all danced

· Oct. 7, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In the modern world of texting shorthand slang, there are two acronyms that describe what happened when Texas and West Virginia played their first Big 12 game against each other at Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium Saturday.

The first is “OMG” – of which the most politically correct definition is “Oh My Gosh.”

The second is “VWP” which – if used at the final checkmate of a great game of chess – would find the conquered opponent saying to the conqueror, “Very Well Played.”

It has long been established that there are no “moral victories” when it comes to Texas football. That’s why the application of the ‘Horns’ “24-hour rule” (which allows reconsideration of the game for 24 hours, win or lose) is all the more necessary after the electric evening witnessed by a mega-national television audience and the largest college football crowd in state history.

When you win or lose, 48-45, in a football game that was more like a serve-and-volley tennis match, you can look at a handful of plays or events that made the difference for both the team that had the 48, and the team that had the 45.

It goes back to something that Longhorn legend James Street told his future Major League Baseball all-star son Huston:

“If you prepared as well as you could and played as hard as you could and the other guy wins, then walk across the field and congratulate him. Because on that night, he played better than you did.”

But for those who experienced the experience of the amazing crowd reaction and the quality of play by both teams, Saturday night should underscore the very best qualities of college football. In the state of Texas, college football is nigh onto a religion, and we worship it because it can exhilarate and depress – both at the same time. It is the perfect teamwork example that sport imitates life – a game played by imperfect young people who are pieces of adults.

The entire evening was a showcase of a new era of Longhorn football. In the last 50 years of football in what is now Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, there have been only a handful of games that this battle of new league foes could be matched against. Oh, there have been great opponents and great wins and a few significant losses, but the last time the Longhorns lost a conference shootout like this was a 14-13 game in 1964 when Darrell Royal and Frank Broyles of Arkansas ruled the old Southwest Conference. Losing close conference games in the final seconds has rarely been the Texas playbook in Austin.

Time will determine the place in history that this game will occupy and the immediate disappointment of the loss will give way almost immediately to the preparation for the upcoming Red River Rivalry battle with Oklahoma in Dallas this coming weekend. But for those who were there, it will forever be remembered as the night the stadium came alive. And because of one man’s quick decision, it will go down as the night we all danced.

Jeremy Armstrong is the new Director of Events for Longhorn athletics, and as such he is responsible for helping infuse the atmosphere at Texas games. Drawing from his experience in a similar role at Cowboys Stadium in Dallas, Armstrong seized the moment when the Texas defense sacked quarterback Geno Smith and recovered the ensuing fumble for a touchdown that tied the game. While the TV replay booth examined the play, Jeremy whisked through his musical memory and ordered the playing of “Jump Around,” a 1992 song originally recorded by the group House of Pain. Soon, the Longhorn team had joined in, the student section had adopted it as their new theme song, and even the old folks on the west side were rocking and…well…jumping around.

The Longhorns who played this game will remember it as one that got away. It truly was like a tennis match, where you had to finally have two straight scores to win. It didn’t happen for Texas, and it did for West Virginia. In the locker room after the game, Mack Brown gave credit to the Mountaineers (who clearly could be the best team in the country right now), and he reminded his team that this season in the Big 12 has a long way to go. A quick glance at the weekend’s results reflects the power of what appears to be the strongest league in the country.

The game, and the night, will go to the bookshelf right alongside the last minute win at Oklahoma State just a week before. Your goal when teaching young people is that they will see what they did well, and learn from opportunities missed.

The credit to Saturday night, however, will come from the reaction of everybody there to House of Pain’s song. Perhaps unnoticed in the amazing scene of the Texas players and fans dancing was the fact that the West Virginia players were dancing, too. The Mountaineers’ outstanding quarterback Geno Smith addressed the atmosphere in his post game comments when he said, “we were having a blast.”

It is perhaps easier to do that when you win, and it is certainly not fun to lose, but in the grand scheme of things it is important to remember that this is a game, played by young people. They “get it” because they love to play. They are glad when they win and sad when they lose. Most of all, however, it is the joy of the competition which motivates them, moves them, and makes them jump.

05.28.2009 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Following the path

· May 28, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

As Mack Brown prepares to leave for his trip to visit American troops in the Middle East, Dallas attorney Scott Henderson remembers.

For Henderson, an all-American linebacker and a three-time academic all-American for the Longhorns 1968-70, Brown’s trip recalls vivid recollections of the summer of 1970, when he and other collegiate stars took a similar trip to visit hospitals and the war zone during the Vietnam War.

Thirty-nine years ago this summer, Scott Henderson carried the Longhorns banner that Brown will be taking with him on an eight-day trip that will include stops in Iraq and Kuwait. He remembers seeing the spot where a bullet hit the propeller shaft on the helicopter he and fellow stars Larry DiNardo of Notre Dame, Mel Gray of Missouri and Scott Hunter of Alabama had just flown into a fire camp on.

“What I remember most of all were those moments out in the field, where most of the USO visitors didn’t go,” Henderson said. ” And I remember the hospitals. There is nothing that prepares you for that.”

In those days, long before television brought games live to the other side of the world and tapes and DVDs captured the action, all the guys who were traveling as part of an NCAA sponsored trip had with them was some film and a 16MM projector. They spoke to as many as a thousand, and as few as a handful.

“We were never close to the DMZ, but the fire camps we visited were outposts,” he said. “That war was really the beginning of some of the kind of warfare we see in the Middle East. The jungle paths could be booby-trapped, and there were suicide bombers, just like we see today. In that way, the fighting was similar.”

Looking back, Henderson remembers names and places which later would become a part of history. He stayed at the hotel where dignitaries and journalists were housed. They visited the American Embassy where a few years later people were airlifted by helicopter as the city was overrun by North Vietnam troops. They posed for pictures with South Vietnamese troops and American “advisors” in the Mekong Delta.

“It was a beautiful country,” he said. “And I understand that today in much of the country, even though it is communist, it is hard to tell that there ever was a war.”

Most of all, Henderson remembers the one on one visits with the GIs.

“Those were in the days when almost everyone there had been drafted, and they served for a specific time,” he said. “Every guy we talked to knew to the day when their tour of duty would end…and the Army stuck to those dates.”

“The easiest way to start a visit,” Henderson said when he returned, “was to ask them what they were doing, and get them to explain some of their business. In 30 minutes time you had a good session going – which was really unfortunate, because we had to leave about the time we got going good. One of the major complaints was that the enemy would start firing on them when they were listening to a football game on the Armed Forces Radio Network. They said it seemed like some of the time the enemy didn’t really want to kill you – just make it so miserable you couldn’t stand it.”

At a time when much of the United States was in turmoil over the Vietnam War, the football players brought a non-political approach and provided a respite to young men their own age far from home, and in harm’s way.

“I admire people who still do their job with a great deal of confidence and competence regardless of the difficulty,” Henderson said then. Of all the men he encountered, the helicopter pilots drew his admiration the most.

“Without the helicopter pilots, the war would be more brutal, because land travel can be made almost impossible,” he said. The bullet which struck the `copter shaft “was just a single bullet and it probably came from three guys lying in the grass, but it only takes one well placed bullet to bring one down.”

Almost 40 years later, much has changed in the way wars are fought, but what is similar, Henderson feels, is that those who are fighting and those who are reporting about it seem to always give a different view.

Though his visit was limited in time, it turned out to be prophetic historically. He came away with the impression that, one, reporters often present a biased view of the situation, and two, the United States must be extremely careful how its power is used.

“We had the power and the might, but they (the Viet Cong) just kept the war going until we didn’t want to fight any more.”

Today, Henderson ocassionally works with a large group of Vietnamese attorneys in Dallas – children of those who evacuated the country as the Communists took over.

“It is a visit that can change your life,” he says. “It was a tough trip for us, but not nearly as tough as it was for those guys who were out there fighting for us, and not getting much credit for it back home. We were there for a few hours, and those guys lived every night concerned about attacks.”

Henderson returned to Texas in time for fall practice prior to the 1970 season. The Longhorns were in the midst of a 20-game winning streak, a string that would stretch to 30 before it ended in the 1971 Cotton Bowl. He finished his senior season by earning both all-Southwest Conference and all-American honors, and is one of the few players ever to earn first-team Academic All-American honors three consecutive years. After his undergraduate work, he earned a law degree and has practiced in Dallas for more than 30 years.

On the other side of the world, the brief moments he and the other stars had spent had made a difference to those whom they had seen, and all that they had seen had made a difference for them.

“I am so glad that Coach Brown is doing this,” Henderson said. “It will be tiring, and there will be things, both good and bad, that will surprise him. Will it be worth it?

“Yeah, it was for those guys. But most of all, it was for me.”

10.05.2012 | Football

Bill Little commentary: New folks

· Oct. 5, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In the mid-1950s, the area in northern Runnels County around the town of Winters was thriving in the midst of the discovery of a shallow oil field. That meant that our little town was the beneficiary of an influx of executives and employees of companies associated with the oil industry.

It may have meant new money and new homes in suddenly created subdivisions to the adults in Our Town, but for us kids it meant only one thing: “New Folks.”

The transient nature of the business meant that some friends would come and others would move on, but the overriding excitement of newcomers trumped the sadness of departures. New kids translated into “new friends.”

That is the feeling as West Virginia heads into Austin for the first meeting in Big 12 competition between two schools with highly respected athletics programs and top ranked football teams.

What began seventeen football seasons ago as a dramatic reorganization of two conferences – the Southwest Conference and the Big 8 Conference – the Big 12 has now seen the departure of four of the original dozen members over the last two years.

The season of 2012 marks a new direction for the league; part of a changing landscape of college football nationally.

Two new schools – TCU and West Virginia – are the latest additions to the league which has been a dominant force in the post season BCS National Championship picture, dating back to the late 1990s.

Coupled with the changes in the conference in which Texas competes are future changes on a national scale. In a couple of years, the BCS as we have known it will give way to a four-team playoff to determine who wins the national title.

All of that, however, is in the future. The present offers a new and exciting landscape for Texas football. It will also be one of the most competitive.

Perhaps as never in its history, the Big 12 – at least from a pre-season view – appears to have more teams capable of winning its title than ever. Of the ten league teams, at least one media representative tabbed six different teams as a potential winner.

The Longhorns history with the two newest members is about as diverse as it can get. West Virginia, which will play the Longhorns in Austin on Saturday, won the only meeting between the two schools, 7-6, in 1956. The ‘Horns that year went 1-9 the year before Texas brought in Darrell Royal as the new coach.

The Horned Frogs of TCU, on the other hand, are one of the oldest rivals in Longhorn history. The two schools, which last met in a non-conference game in 2007, first played in 1897. Beginning in 1923, the two schools were members of the Southwest Conference until the league disbanded after the 1995 football season. When it hosts the Frogs in the final home game of the 2012 season, Texas maintains a 61-20-1 edge over TCU – including that 34-13 win five years ago.

The massive changes in the college football landscape began in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Penn State announced its intention to join the Big 10 Conference. Soon afterward, Arkansas declared it was moving from the Southwest Conference to the SEC. The 1980s had been a traumatic time for the Southwest Conference.

Where the 1970s had reflected growth in the league with the addition of the University of Houston, the 1980s had seen the dark clouds of scandal cover the league. SMU rose to national stature in the early part of the decade, only to have the football program eliminated in the NCAA’s only “Death Penalty” in its history in the middle of the 1980s. TCU received a stern penalty and before the purge was over, nearly every school in the league had been implicated in violations ranging from minor to major.

It was under that umbrella that new horizons appeared possible for schools such as Arkansas, Texas, and Texas A&M. The SEC and the Pac-10 both showed significant interest in the two Texas schools, with the Razorback nation holding out hope that they would join them in the journey to the SEC.

The initial response was to try to hold the Southwest Conference together, holding fast with its eight schools – Texas, Texas A&M, TCU, Texas Tech, Baylor, SMU, Rice and Houston as members.

But as the 1990s proceeded, the large shadow of the television industry began to influence decisions. The Big 8 Conference, whose schools were linked geographically in the Midwest, had only seven percent of America’s TV sets. The Big 10 had over 30 per cent, and the SEC 23 per cent. Even though Texas teams brought major television markets in Dallas and Houston, the SWC had only seven per cent coverage itself.

The first option for the SWC and the Big 8 was to attempt a coalition that would entice the networks. When that failed, so did the leagues. The popular thought was that four Texas schools – Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Baylor – elected to join the Big 8. But the fact was, the Big 8 had no regional television package and was actually in more trouble than the SWC. So the result was that both leagues disbanded, and the eight schools in the Big 8 and the four Texas schools formed a league of a dozen teams known as the Big 12.

Among those left behind, of course, was TCU. In the years since, TCU has become a respected football program, and with the combination of the Frogs and West Virginia, the Big 12 has added national respect – reinventing itself just when many rumors had the league on the brink of extinction.

The history of the Texas-TCU series is rich with some of the greatest figures in football in the southwestern United States. From the 1920s and 1930s, when Sammy Baugh and Davey O’Brien were becoming almost mythical heroes on the Fort Worth campus, through the time of Bobby Layne in the 1940s, and Roosevelt Leaks and Earl Campbell at Texas in the 1970s, the series was a mosaic of gridiron glory.

West Virginia, on the other hand, is truly the “new friend” in the equation. When the two top ten teams meet Saturday, it will bring together two schools who have a kinship of excellence when it comes to athletics competition. The fan bases of the two schools, as well as the national media, has taken notice. With a reputation of passionate fans and excellent football, the Mountaineers extend the borders of what once was a Midwest-Southwest venue. The television cameras (not to mention the networks) will relish the new rivalries featuring the two new schools with the established programs in the Big 12.

As they did last season, the Big 12 under its new alignment will see all ten teams play each other, as well as the elimination of a conference championship game. That, in its own way, will change dramatically the sense of the campaign.

That is why, as the media pundits and prognosticators try to predict the league’s navigation through this 2012 season, it becomes darn near impossible to handicap the finish.

For the first time in its existence, every team in the league will likely be thinking at the season’s beginning that they have a legitimate chance to win. Where in the “old” Big 12 Oklahoma and Texas, for example, might go two years without playing a Nebraska or a Colorado, now West Virginia will play at Texas, and Oklahoma will be visiting the Mountaineers.

That is why there is excitement throughout the league, and why the Longhorns are committed to their team motto of “RISE.” This will be a rugged campaign, and it will play out with a lot of interest on a lot of levels.

It is, as it was, in Winters in the 1950s. You’ve got new friends, and therefore new competitors. Winning this league will be harder. Everybody is going to want to date the prettiest girl in town. There is strength in the completion, and power and prestige in the camaraderie.

Most of all, it is an intriguing and exciting new world.

New folks have a way of opening new windows, providing new horizons, creating new friendships, and by definition, new rivalries.