Bill Little Articles part VI

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

A Reason to be Thankful

-

Outside the Wire

-

Burnt Orange Sunset

-

Welcome to the Neighborhood

-

Momma’s Rose

-

To Tina Bonci, with Thanks

-

The Colors

11.23.2005 | Football

Bill Little commentary: A reason to be thankful

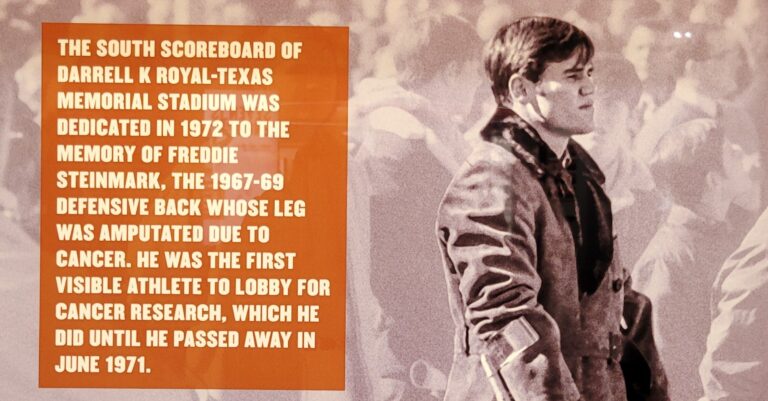

It was, and remains today, one of the most powerful pieces of journalism I have ever read. Fred Steinmark, the little safety on the 1969 National Champion Longhorn team, had just died. Blackie Sherrod, one of the best writers in a time of simply great sportswriters in Texas, had co-authored a book with Freddie.

Blackie wrote a column about Steinmark, and he closed it with a story about the dedication of the book. At the time, Freddie was an athlete dying young. He was in his early 20s, with a promising life ahead of him. He was a gifted athlete, whose leg had been removed from the hip because of the cancer that would kill him.

“Freddie has written a book about his experiences,” wrote Blackie. “It will be published this fall. The editor noticed after Freddie was hospitalized, that he had not made a dedication of the book and he asked to whom Freddie wanted to dedicate his story.

“Freddie said to the Lord, who had been so good to him.”

In trying to write a column about Thanksgiving, 2005, I have thought a lot about that. Our wonderful world in Texas athletics is juxtaposed with a really hard year in America. With a little over a month remaining in this calendar year, Longhorn athletics are at an all-time high.

It began with the Rose Bowl win on January 1 in Pasadena. Baseball, and women’s track, claimed National Championships. Collectively, the athletes at The University of Texas, despite competing in fewer sports than their counterparts, finished second in the competition for the trophy honoring the most successful collegiate athletic program in the country. The Autumn of the year continued to be promising. An undefeated football team, and both the football and basketball teams ranked No. 2 in the country.

But in the real world, and reality in this case really does bite, the picture dims. Natural disasters. War. Heart-breaking tragedy. Even the cost of a tank of gas. And if we do have a chance to begin to feel good, all around us there are those who will remind us just how miserable we ought to be.

In the midst of all of this, we turn to sport as a release. We celebrate success, because it reminds us that the human spirit can conquer. In most cases, it is a game or a season. In the case of Freddie Steinmark, it was more than that.

“His friend thought it was rather a miracle, Freddie having played regularly on a national championship team with the tumor already gnawing at his leg, and had survived the amputation and returned to active life…had been able to move back into society, to tell people how he felt, to squeeze another 17 months out of precious life,” wrote Sherrod when Steinmark died a year and a half after his cancer was discovered following UT’s last regular season game of the National Championship season of 1969. Freddie had started every game of the season, including the famous “Game of the Century” with Arkansas.

But Sherrod continued, “Freddie didn’t think it was a miracle; it was what an athlete was supposed to do and now that same fierce competition kept him hanging on for days, weeks, after the average person would have let go.”

We get that in sports. We get the competitor, we get the pride, we get the joy of victory, and we even at some level feel and understand the agony of defeat.

But where in the world do we really begin to understand Steinmark’s final words. How in the world, do we look beyond the pain, beyond the hurt, and be thankful on Thanksgiving Day?

I remember Dr. Gerald Mann, then pastor of Riverbend Church, saying the only way to deal with grief is to replace it with gratitude. If that’s the case, then it is incumbent on us to open our eyes, and our hearts to what we have to truly be thankful for.

The origin of the day is about that. We are told that the first Thanksgiving Day was observed by pilgrims who had lost family, friends and had endured many hardships as they left their roots to begin life in a new land. The bounty they were thankful for was meager, but somehow they found power and conviction to persevere.

In many ways, there are thousands of people in America today who can relate. Driven from their homes by the forces of nature, their choice is to grieve over what was, or to be hopeful of what can be.

On Thanksgiving morning, as they have for the last eight years, Mack Brown‘s football team, the players and the coaches only, will gather in the team room at the Moncrief-Neuhaus football facility for a meeting. They’ll hear a brief inspirational message, and then each player or coach will have a chance to stand up and tell his teammates and coaches what he is thankful for.

It is a powerful, emotional time, where the common thread of togetherness, the strength of the love of each other, bonds 100 or so guys in an incredible way. The challenge of saying what’s in your heart can only be accomplished in a space of complete safety, and Thanksgiving morning in Austin, the sanctuary of the Longhorn football dressing room is the safest place on earth for the players and coaches.

Outside, toward the field of Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, Freddie Steinmark’s picture hangs in the tunnel by the scoreboard that bears his name.

He would be proud of the session in the room, just a few paces away, because it reminds all of us that it is important to see the good in life, to sift through tough things and tough times.

What you hope is, hard lessons teach positive futures. Today, the cancer that killed Freddie is almost completely curable, because of the research done in the years since 1970. We hope that peace comes in our world, and when it does, it will be in part because of the sacrifice of others.

In athletics at The University of Texas, we are arguably in the very best of times, and there is reason to be thankful for that, not because the Longhorns win, but because the manifestation of team success is a celebration of individual achievement, and we salute that.

More than that, however, these are young people who have not only touched each others’ lives, they have touched our lives. They have given us joy, and they have allowed us to share in their fun.

They have allowed us to vicariously live in the distinct quality of a dream, to feel the celebration, to appreciate the success. They remind us every day that youth and team and character and excellence are gifts.

And for that, on this day, in this particular window of life, we have reason to be thankful.

11.09.2005 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Outside the wire

It is a space where few of us, really, have had to go.

They call it, “outside the wire.”

On Saturday, as we celebrate senior day and observe the final home game of a superb 2005 football season, as letter winners gather in reunion, we also pay tribute to the reason this stadium stands in the first place.

Texas Memorial Stadium was built in 1924, as a shrine to those Texans who had fought in World War I. They called it “The Great War,” and they hoped there would never be another.

But there was another. And another. And another, etc., etc., etc.

That is why, at the north end of the facility which now shares its name with UT’s legendary coach Darrell Royal, there is recognition of most of the worldwide conflicts in which veterans of the Armed Services of The United States of America have fought.

At the top of the north stands, the monument is dwarfed by a scoreboard and even blocked by camera scaffolds. But it is there all the same, dedicated to those Texans who died in WWI. The stadium has been rededicated several times, most recently in 1977, when it was recognized to include all veterans of all wars.

Each year, a specific game is set aside as “Veterans Recognition Day.”

A Veterans Committee, chaired by Frank Denius, stands sentinel on the day, making sure the purpose of the stadium’s original charge is never forgotten. Denius is the ideal person to chair the committee, because he remains one of The University of Texas’ greatest supporters, and he is also one of the ten most decorated soldiers from the European theater of World War II.

Denius and the committee are hosting 75 soldiers from Fort Hood who have served in battle recently. An F-18 flyover, and a special National Anthem performance will highlight the day, and the soldiers will be honored both at the game and at a barbecue for them that will follow.

In the southeast corner of the stadium, a wreath will be placed at the Louis Jordan Flagpole, in recognition of UT’s first letter winner killed in action in France in WWI.

All of this is pretty standard for this day…a day where it is important to remember the past. But it is also important to understand the impact of the present.

“Outside the wire” is the area where today, men and women of The United States of America put themselves in harm’s way for the cause of freedom. And no one understands that more than Longhorn fullback Ahmard Hall.

Don’t hold me to this, but this is how I remember it.

David Little, our youngest son who is a 38-year-old Austin lawyer with three young kids, had just been recalled from inactive duty status to serve as a major in the United States Marines in Iraq. He returned from serving as a JAG lawyer in the volatile Al Anbar province about a month ago.

I had talked often with Ahmard Hall about David, since they shared the bond of Marines. David had just left when I ran into Ahmard outside the football offices and told him David was on his way.

With a look of compassion, caring and concern, his bright eyes flashed.

“He will be watched over,” I remember him saying.

You could take that a lot of ways, all of them positive. But what I know most of all about Ahmard Hall is that he epitomizes the motto of the Marines: “Semper Fidelis.”

Always Faithful.

Earlier this year, the Big 12 Conference chose him as the male athlete winner of the 2005 Sportsman of the Year Award.

For the record, here is the criteria:

1) Nominee must have demonstrated consistently good sportsmanship and ethical behavior in his daily participation in intercollegiate athletics.

2) Student-athlete must have demonstrated good citizenship outside of the sports competition setting.

There are a couple of other house keeping items, such as being in good academic standing and having been a member of a team during the 2004-05 school year, but those are standard on any award punch list.

In a day when there is a lot of negativity in our world, Ahmard Hall’s story is heartwarming. On September 11, 2001, he was on a ship on a tour of duty in Kosovo.

That day, he reassessed his life.

His dream had always been to play college football, and his old teammate at Angleton, Quentin Jammer, was a star player at The University of Texas. That day, Hall determined he would fulfill that dream. He went on to serve as a Marine Corps sergeant in Kosovo and in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.

By the time his four-year term was over, he had attained the rank of sergeant, and had earned enough credit to attend The University of Texas on the G. I. Bill. He is married. He and his wife, Joanna, who is also a Marine reservist now, have a two year old son, Mason.

When he approached Jeff Madden and the Texas coaching staff about walking on to the Longhorn football team, his condition was astounding. Marines are like that. His work ethic soon manifested itself as well, and by last fall, he was a member of the kickoff teams and was earning a spot as a back up fullback.

Meanwhile, both he and his wife were working to make ends meet. Despite not playing football for four years before he returned to school, he has played the 2005 season as the starting fullback on one of America’s best football teams. He has played the game with passion, but he has treated his teammates and his opponents with respect. He works with community service, and is a constant inspiration to younger Longhorn players because of his work ethic, and his life’s path.

Prior to the Texas-Arkansas game in Fayetteville on the second anniversary of 9/11, Hall was asked to lead the team on the field with the American Flag. He did it every game following that, including the Longhorns’ historic appearance in the Rose Bowl.

At the Longhorn football banquet, Hall was chosen to receive the inaugural Pat Tillman Award given in honor of the former NFL Player who was killed in action, but he wasn’t there to receive it. Instead, he was home baby-sitting so his wife could work overtime hours to earn credit so that she could make the team trip to the Rose Bowl.

Hall is currently in the inactive reserve, but could be recalled to duty at any time, and he knows it. But when he finishes his degree, his opportunities are limitless, and might even include a chance at professional football.

Right now, he is the Longhorns’ high profile representative as a statement to patriotism. When the Texas Legislature honored the team for its Rose Bowl Victory, Hall was one of two players they asked to come to the House floor to accept the award. As a Veteran’s Day project last year, Hall helped the Longhorns organize a drive to provide care packages to the Marines in combat.

The Big 12 gave their award to a guy who is a real American hero. He is a dedicated husband and father, an unselfish and caring teammate, and a proud Marine.

They say “the Lord helps those who help themselves,” and Ahmard Hall has certainly done that.

But what we know most of all, when it comes to “watching over” folks, Ahmard Hall is both a participant, and a recipient.

When David Little left Iraq, he sent an e-mail to friends and family.

“I cannot leave this place without remembering those who will not return,” he wrote. “Both friends and Marines and sailors I did not know shed their blood and gave their lives here. They believed in what they were doing. They took a stand and made a difference with their lives, and are to be respected for that. They stepped up and faced death so that others would not have to, and they are to be honored for that. And, they gave of themselves selflessly so that my children and yours can play in the yard, go to school, and live their lives without the constant fear of an attack from evil terrorists. They are to be thanked for that.”

There is no better tribute than that, and no better representative of what it all means than Ahmard Hall. For he, and those others we honor today, have gone “outside the wire” for all of us.

12.02.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Burnt Orange Sunset

As the seniors took a victory lap after the game and the Tower switched to orange, Texas had moved its record to 8-3 and stood at 7-1 in league play.

The southwestern sky looked as if it were brushed by that old master painter from the Hill Country as the Texas Longhorns concluded their Sunday practice at Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. The rolling clouds were a wintry mix of majesty and wind.

It was, by the way, dead-solid tinged in burnt orange.

Senior day had come and gone on Thanksgiving night, and the days that followed offered perhaps the most exciting college football in recent memory. Not lost, however, in the hustle and bustle of it was the fact that Texas—yes, Texas—has put itself into a position to play one game where a victory would earn it at least a piece of the Big 12 Championship in 2013.

The doubters have been many. When the Longhorns lost to what has turned out to be a very good Oklahoma State team just a couple of weeks ago, the faint of heart faded. The naysayers abounded. Never mind that this team had won six straight league games. Forget the fact that this season is the most balanced in league—and perhaps national—history.

Thursday night in the seniors final game in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, Texas thrust itself right into the title mix with a dominating 41-16 victory over a Texas Tech team which had been ranked among the nation’s top ten just a few weeks ago.

And with that, they validated the dream of the Big 12 Conference when it chose to avoid a “championship” game between two divisions. What it has now is an unparalleled “championship weekend.” In games in Waco and in Stillwater, the contenders will play each other to determine the champion of a league which has seen each team spend nine of its games battling each other.

Texas, Oklahoma State and Baylor each have one league loss. The ‘Horns play the Bears. Oklahoma State plays Oklahoma, which has two losses. At one point Saturday, when Baylor was holding on for dear life against TCU in a 41-38 victory, there was a very real possibility of a four-way tie at the end between Texas, Baylor, Oklahoma and Oklahoma State.

Now, it has come down to a winner-take-all game between the Bears and the Longhorns to earn at least a piece of the championship. That is why, as the Longhorns began preparation for their trip to Waco, it was significant that the sunset was burnt orange. In a season of miracles, omens are good things.

In a well-publicized season that began with a win and two straight losses, it seemed improbable at best that Texas would fight its way to this position. More than a dozen Longhorns have gone down to season-ending injuries, including seven who have started at least a game.

In so many ways, this has been a season of retribution for Texas. It is a marvelous story of retribution, of redemption. There was a defensive coordinator inserted into the season after the third game, a guy who was looking to get back into the game he loved—a Super Bowl and Rose Bowl champ who was coaching in high school just to stay in the game until he got the call to come to the rescue of a Longhorn defense.

There was a quarterback who had accepted his role as a backup after coming to Texas four years ago with dreams that had been shattered…a kicker who had transferred last year and spent the year struggling with painful injuries…a defensive leader who had seen his last two seasons ended with torn pectoral muscles…two running backs who had struggled with injuries in each of the last two years…and a head coach who was only four seasons removed from a National Championship game, and had gone through the pain of reinventing himself and his program.

And so, here were the Longhorns on Thanksgiving night, trying to snap an uncharacteristic three game losing streak on senior night, and keep their dream of playing for the Big 12 Championship alive.

They did it with a dominating performance. The defense hammered a Texas Tech offense which had been leading the nation, and the offense rushed for over 300 yards and came from behind to completely control the game. The second half told the story—Texas held the ball for twenty minutes to only ten for the Red Raiders. Tech quarterbacks were sacked nine times, and Case McCoy seized his senior moment to throw two touchdown passes and rush for another.

As the seniors took a victory lap after the game and the Tower switched to orange, Texas had moved its record to 8-3 and stood at 7-1 in league play. They had done this, not as individuals, but they had done it together. The glue which had held them together through the tough times remained the bond of their theme—they play for the man on their left and the man on their right—in other words, they play for each other.

Sunday’s recognition practice began the focus on Baylor, which will bring a 9-1 record into their final game in Floyd Casey Stadium in Waco. Saturday, we had all watched college football at its finest—with last second wins, upsets, narrow victories and narrow losses.

What happens from here, only Saturday will determine. What we know is, this team which has found a love for each other and elicited support from its fan base, now has a chance to put everything on the table.

Kipling talked about this when he said “if you can make a heap of all your winnings, and risk it on one turn of pitch and toss….”

That is why Texas will spend this week getting ready. They have earned a shot. And that is all they have really asked for in this very strange, yet very special season of 2013.

11.28.2002 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Welcome to the neighborhood

Okay, quickly now, name the only three teams in college football that have been ranked in the top dozen of the BCS Standings at the end of each of the last two seasons and were ranked there this year going into last Saturday.

If you said Miami (Fla.), Oklahoma and Texas, you were right. If you want to take it a step further and mention the only two teams who were ranked in the Top 10 of the BCS standings last year and were in that elite crew as of day break last Saturday, that would be down to only Texas and Miami.

When UT head coach Mack Brown sat down at a press conference at the Big 12 Championship game at the close of the 1999 season, he talked about the neighborhood of college football’s prime real estate. At that point, he said the Longhorns had visited the neighborhood. Now, they wanted to buy a house.

With Brown on that trip was a freshman class with great dreams, and today, we say good bye to some of them. As they prepare to play their final game in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, it is appropriate that we pause to pay tribute to the house they have built and the land that they have purchased.

Purchased and built are appropriate words. They bought it with a lot of sacrifice and commitment and built it with hard work and exceptional talent.

Including transfers and a sizeable contingent of volunteer players known as walk-ons, this group of seniors has helped re-establish Texas as a force in college football. The last four years has produced a 38-12 record with two games remaining in this season. That equals the most number of wins recorded by a four-year senior class, set by last year’s at 38-15. One more win and these guys will have won more football games than any Longhorns class since freshmen became eligible in 1972.

Perhaps more significantly, however, is that fact that the last three years of Texas football have produced the best three-year period in 20 years. In the last three seasons, Texas is 29-7, the best mark since the teams of 1981-83 finished with a 30-5-1 record.

From the moment since Georgia recovered a fumbled punt late in the 1984 Cotton Bowl, consistent excellence had disappeared from the Texas landscape. David McWilliams’ team of 1990 did, in fact, “shock the nation,” as it finished the regular season ranked third nationally. But the very fact that they used the term “shock” tells you a lot about where the program had fallen.

Unfortunately, the success could not be sustained.

The Cinderella season of 1998 produced a lot of fun things and a Heisman trophy for Ricky Williams, but what got the most attention was the signing of a heralded recruiting class in Brown’s first full year in the trenches of the recruiting wars. Today, we bid farewell to some of them.

Of the 27 signees, this will be the final game for seven of them. In the 24-member senior class, they are joined by four scholarship seniors from Brown’s first signing class in 1998 and 13 players who joined the troops along the way. Eight other members of the class were redshirted and are playing in their junior seasons.

However, for CB Rod Babers, OT Robbie Doane, OG/T Derrick Dockery, DE Cory Redding, QB Chris Simms, TE Chad Stevens and FB Matt Trissel, this will be their last trip out of the smoke and into the brightness of the most beautiful stadium in the nation. OG Beau Baker, LB Lee Jackson, DT Miguel McKay and ST Beau Trahan are the representatives of Brown’s inaugural class. Those four guys have been a part of five consecutive teams that have won at least nine games, the first time in school history that has happened.

The list of seniors bidding farewell also includes ST Richard Hightower, WR Kyle Shanahan and ST Michael Ungar, as well as P Brian Bradford and OT Alfio Randall-Veasey. The rest of the class includes DB Paul Campion, TE Josh Doiron, DB Brandon Hedgecock, RB Casey Martin, PK Dan Smith, OL Keith Virdell, LB Cory Weideman and DB Billy Wright, all guys who worked hard every day in trying to help this team be successful.

The recruiting class of ’99 was ranked as the best in the country, and if this was all about a house in the neighborhood, credit these guys with laying the solid foundation. In a perfect world, more of them would have been able to redshirt. The Longhorns are redshirting 19 players this year, but when those guys arrived in fall 1999, the talent pool was exceptionally thin, so many of them had to play immediately.

Little could they have realized, just those short four years ago, how their lives would change after they became the last signing class of the 20th century.

There would be victories and joy – they won two Big 12 South Division Championships along with all of the wins they notched and they will have played in four bowl games. However, they also would witness heartache, on and off the field. When they were only freshmen, they saw tragedy for the first time when the Texas A&M Bonfire fell in 1999 and kids passed away before the game.

In spring 2001, it would come even closer to home, when a teammate died in a car accident on his way back to school from home. For some, it would be the first funeral they ever attended. It is significant to note that this would have been Cole Pittman’s last home game too.

They set their goals high and were determined to play at the highest level of college football. When you risk much, you can lose much. That was the pain of the oh-so-close runs for the chance to play for a National Championship the last two seasons. However, it is important to note again that the only two teams in the country to be in that position both now and at the end of last year were Texas and Miami.

The final 10 a year ago included Miami, Nebraska, Colorado, Oregon, Florida, Tennessee, Texas, Illinois, Stanford and Maryland. Last week’s Top 10 BCS Poll ranked Miami, Ohio State, Washington State, Oklahoma, Georgia, Notre Dame, Iowa, Southern Cal, Michigan and Texas.

In terms of numbers, this collection of seniors we recognize today is a small class, but each person has a story and leaves us with a memory. Most of all, the gift they have given us is the right to be prideful again. The chance to celebrate young men, not only for what they have done, but for who they are.

The years will be kind to them, as the record and history books tell their story at Texas. The memories, both good and bad, will blend together.

Darrell Royal, in speaking to Brown’s first senior class, gave them a saying that is posted in big letters outside the dressing room door in the Moncrief-Neuhaus Athletics Complex.

“What I gave, I have,” it reads. “What I kept, I lost.”

His message was about team, and more than any single factor, that is what these guys have been about.

It has been about joy and sadness, commitment and sacrifice, glory and honor, legends and legacies.

Most of all, however, it has been about each other and that is what they will have long after the records are broken and the games are played only in the memory. It is then that they can truly take a look at the neighborhood, with its grown scrubs and climbing ivy and manicured lawns. They will remember a time when they took Texas and put it there.

12.25.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The last ride

Following a Sunday morning practice, the Longhorns headed home for the holiday, and will regroup in San Antonio on Christmas night, beginning their final bowl practices on Dec. 26.

He was standing about where he had been walking with Darrell Royal that early spring day, just a few feet from where Mike Campbell had sat looking and listening when Mack Brown‘s first Longhorns defense took the field for their initial practice.

Time had changed a lot of things. The hair was gray now, and the assistants had changed. An indoor practice facility now covered the corner of the Denius practice fields where the old Villa Capri Hotel had once hosted Royal’s famous postgame media meetings in another time.

The Longhorns of 2013 had finished their final practice in Austin, and in keeping with seemingly everything else in this season of change, the last practice had been moved from Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium indoors because of a chilly wind. The final game — against Oregon in the Valero Alamo Bowl on Dec. 30 — will be played inside the Alamodome.

As Mack joked with his team and assistants gave instructions to the players about the bowl schedule, he finished with the usual comments about being careful on their travels home from Austin and back to San Antonio on Christmas night. A week before, Brown had apologized to the team and to recruits and their families for the disruptive distractions during their week of final exams. Throughout all of turmoil, while the college football world pondered who would be the next Texas coach, this Longhorns team has been preparing to play one final game with a chance to improve on their regular season record of 8-4.

The close of practice usually comes with a brief meeting, and ends with a coming-together team huddle that finishes with a slogan shouted by featured leaders. It has been tradition for that final practice in Austin to be led by the seniors. This time, however, the team which made a vow to play for each other took over. As Brown called for the seniors, All-American Jackson Jeffcoat stepped forward. On behalf of the seniors, he said, they felt that final honor should go to Brown, in what would be his last appearance as the Longhorns’ head coach on the practice field in Austin.

Sixteen years is a long time, particularly in the collegiate coaching profession. And with the changing of the head coach, there is also a changing of the guard. Besides the 115 or so members of the football team, there are as many as 150 other people whose lives are directly touched by the football program. When there is a change in the head coach, all know that the direction of their lives may well be altered.

In the week that has passed since Mack Brown announced he was leaving Texas, assistant coaches and all the support personnel whose jobs it has been to help them have worked hard to live in the present. Coaching football is what they do, and it is to that space that they have regrouped and focused on preparing this team to play an excellent Oregon team on Dec. 30.

Brown has said many times this group of young men constitutes one of his favorite teams ever. They have earned that, just as they won respect from many of the Longhorns fans, because of the way they have fought against unbelievable odds in the midst of one of the strangest seasons in Texas Football history.

For the first time ever, they endured two lengthy weather delays that made long road trips even longer. They hit a “Hail Mary” pass at the end of the half against Iowa State, and then won on a last minute drive. They played a showcase game to beat rival Oklahoma in Dallas, and won in overtime at West Virginia. Along the way, they lost seven key players to season-ending injuries, and shuffled lineups because of others who were dinged and slowed.

And even with all of that, they were tied at halftime and only 30 minutes away from a Big 12 Championship and a BCS bowl game in their final game against eventual league champion Baylor.

With each circumstance, Brown kept repeating that the Longhorns were committed to a theme of playing for each other, and that whatever happened it would be “Next man up, no excuses, no regrets.”

Following the Sunday morning practice, the Longhorns headed home for the holiday and will regroup in San Antonio on Christmas night, beginning their final bowl practices on Dec. 26. The Longhorns under Brown have won nine of their last 11 bowl games. Mack has spent 41 years in the coaching profession, including 30 as a head coach. He is the 10th winningest coach in college football history.

The changes he brought to Texas when he walked onto that practice field with Royal and Campbell as a 45-year-old head coach are well documented. History will remember him for changing the culture of Texas Football, for righting a ship which had been mostly adrift for more than 20 years before his arrival.

In his own way, he became the embodiment of his charge to UT fans to “Come early, be loud, stay late, and wear orange with pride.” In a program built on the premises of “communication, trust and respect,” he delivered both on the field and in the classroom for his players.

That is why Jeffcoat and the seniors conspired to salute Brown at the end of the final Austin practice.

In the book, “One Heartbeat,” Brown put down on paper his thoughts about coaching:

“Your challenge as a coach is to make a difference for people…. That’s part of the joy of coaching, but the hard times teach lessons. There are times when your faith in yourself will be tested. That’s when you need to remember to take pride in what you do and have the courage not to give up. Will Rogers once said, ‘Never let yesterday take up too much of today.'”

And then he said this:

“When it’s all over, your career will not be judged by the money you made or the championships you won. It will be measured by the lives you touched.

“And that is why we coach.”

08.03.2009 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Momma’s roses

ug. 3, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Earl Campbell with his mother, Ann, at the dedication of Earl Campbell’s statue in 2006.

Earl Campbell with his mother, Ann, after Earl won the 1977 Heisman Trophy.

It has been over 30 years, but it seems only yesterday.

I was working late one autumn afternoon when the phone rang in our office.

“This is Kent Demaret of People Magazine,” the voice on the other end of the line said. “And somebody’s been telling me about some great football player you have whose mother raises roses in East Texas. Sounded like there might be a story there.”

I took a deep breath and paused for a moment.

“Let me tell you,” I said, “about Earl Campbell, and his mother, Ann.”

In a few weeks, just as the Heisman Trophy writers were about to cast their ballots, Ann Campbell’s picture was on the cover of the magazine, right there in every grocery story in America.

I thought about that phone call, which has been etched in my memory for all of these years, when word reached our office Monday that Ann Campbell had died, convinced in her own mind that she was heading to a Greater Rose Field somewhere beyond the sky just a few months shy of her 86th birthday. Because in many ways, Ann Campbell was one of the most important women in the history of Texas Longhorns football.

Not only did she raise roses in the Tyler fields, she raised 11 children. Ten of them were high school age or younger when her husband died in 1966. With a strong belief in God and a commitment to hard work and discipline, she reared those children, never expecting that one day, one of them would become arguably the greatest football player of his era.

By the time Earl Campbell was in the running for the Heisman Trophy in the fall of 1977, the legend of Momma’s Roses was gaining national attention. And while Earl was the record-setting running back at John Tyler High School and an All-American at Texas, it was the lady who moved with equal efficiency and grace from the fields to the skyscrapers of Manhattan who clearly was the person who made Earl run.

Once, when a college coach had come to visit Earl in those days when recruiters could come at anytime, Earl sent word that he was just “too tired” to talk to him. “Earl,” said Ann Campbell, “this man had come a long way to see you, now you get up and go talk to him.”

But in a time when recruiting irregularities were rampant, honesty and integrity were the roses Ann Campbell brought forward to a business rift with thorns. This remarkable woman of meager means believed that life was better with a smile on your face, and that “great” was a word reserved only for God Almighty.

When Earl was being recruited, she listened and watched until she finally made a decision that would change forever the face of Texas Longhorns football, and The University of Texas.

Ken Dabbs remembers the moment as if it were yesterday. He can still see Ann Campbell, lying in bed in the tiny house where she lived by the rose fields and raised Earl and his 10 brothers and sisters.

High blood pressure had felled her, Dabbs says, and it was past nine o’clock in the evening, two days from signing day for high school football stars.

Earl Campbell may have been the premier recruit in Texas high school history. He was coming off a spectacular senior season in 1973, where he had led Tyler to the state high school championship.

It was not uncommon for a school to place a young assistant in an apartment in a town where a prized player lived, and for them to woo them at all hours.

Dabbs was the recruiting coordinator for Coach Darrell Royal at Texas. He was a former high school coach in Texas, so he understood kids. He was older than some of his competitors, so he brought respect from parents.

Former head coach Darrell Royal with Ann Campbell at the dedication of Earl Campbell’s statue in 2006.

Earl Campbell with his mother, Ann, and then-head coach Fred Akers after Earl won the 1977 Heisman Trophy.

And at the top of that list was Ann Campbell of Tyler, Texas. In fact, at one point early in the recruiting process, Dabbs had to explain to Momma Campbell that he was, in fact, not the head coach at The University of Texas. That was a guy with three National Championships to his credit named Darrell Royal.

But Ann Campbell didn’t care about National Championships. She cared about who would be the best mentors for her son, and she cared about integrity. When recruiters came at the Campbells with illegal offers, Earl replied with a strong answer that he was not for sale.

After her husband died at a young age, Ann Campbell had supported her family working in the Tyler rose fields, selling roses. She normally had a song in her heart and a smile on her face, but the night Dabbs remembers, the stress of recruiting was getting her down.

Dabbs was practically a member of the family as far as Ann Campbell was concerned. She was a proud woman. The first time Royal came to visit, she apologized to him for her meager home.

“I’ll tell you the truth, Mrs. Campbell,” said Royal, who came from humble beginnings during the Dust Bowl Days in Hollis, Okla., “your house is nicer than the one my grandmother raised me in.”

For Ann Campbell and Darrell Royal, it was always about how you treated people.

As Dabbs was saying good night just a few days before National Signing Day in 1973, coaches from other schools were making their final run at Earl Campbell. And as he turned to go, the phone rang.

On the other end of the line was an Oklahoma assistant coach. He wanted to know if head coach Barry Switzer could come by on Monday for a visit.

Dabbs remembers that Ann Campbell was flat on her back in bed when Earl asked the question about the possible visit.

“She raised up and looked Earl straight in the eye,” remembers Dabbs. “Earl,” she began according to Dabbs, “This has gone on long enough. You know you are going down to Texas with Coach Dabbs and Coach Royal, so you tell them that. Those Oklahoma coaches are the reason I’m laying here in this bed right now.”

Whoops.

In today’s advertising vernacular, the phrase would be, “Can you hear me now?”

History tells us Ann Campbell’s son Earl did come to Texas. He became one of the greatest running backs in the history of both the college and professional game. As a student-athlete at Texas, he became the school’s first Heisman Trophy winner and won every award for which he was eligible. He is in both the College Football Hall of Fame and the NFL Hall of Fame.

He earned his degree, and when he signed his first professional contract, he built his mother a house, in his words, “So she wouldn’t have to look at the stars at night through the holes in the roof.”

More than anything, this was the gift Ann Campbell left us with. In a time of doubt, she believed. When others didn’t trust, she had faith.

In so many ways, it is fitting that she will be remembered for her roses. Because the rose is a flower of beauty, with layers of petals reflecting substance and grace. Most of all, it transitions its metamorphosis through a bud, then a bloom, and finally with petals that scatter, touching lives with a smile and a blessing in all directions.

And that is the story of Ann Campbell.

03.11.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little commentary: To Tina Bonci, with thanks

University of Texas trainer Tina Bonci passes away at 59.

A link to Tina’s story is at the link below

MEMORIAL GIFTS/CONDOLENCES: The family will advise regarding a future memorial service in Greenville, Pa. A recognition event also will be scheduled in Austin late spring. Memorial gifts in Tina’s honor may be sent to: The Longhorn Foundation, The University of Texas/Intercollegiate Athletics, PO Box 7399, Austin, TX 78713-7399, Attn. Rob Heil and note TINA BONCI SPORTS MEDICINE ENDOWMENT FUND on checks. Personal notes of condolence may be sent to: Fred Bonci, 462 S. Dallas Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15208

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

When you think of Tina Bonci, you think of words that begin with the letter “T”.

“T” is for Tina.

“T” is for tenacity.

“T” is for Texas.

“T” is for thanks.

What can you say about someone, who in her 28 years working in the field of athletic training at Texas, touched more people — with her hands and her heart — than could fit into any arena, facility or field where Tina weaved her magic.

There is another letter that would fit. Tina captured the essence of the letter “G.” She was gentle, gracious, giving. She was indeed a giant, and she was very, very good.

As a pioneer in the field of sports medicine, Tina understood more about the human body than a hospital full of specialists. From the mid-1980s, when she served as an athletic trainer for the USA Olympics women’s basketball team, until last weekend when she finally lost a brave battle with cancer, Tina immersed herself in learning.

On the third floor of Bellmont Hall, there was a little cubby hole of a corridor which served as the training room for UT women athletes for years until the men and women’s programs combined their training facilities in the Moncrief-Neuhaus Athletics Center. There, Tina was the master of medicine. Staff or student, hurt a limb and need ice? Go see Tina, just down the hall. The machine was always working. Rehab? Got it. Ankle taping? Sure. Counseling? Sit down and visit.

Tina bridged the gap between genders and age groups. Where the legendary Frank Medina became synonymous with athletic training at Texas during his 33 years between 1945-78, Tina served the women’s program for 28 years and was still a full-time employee at the time of her death. The irony, of course, is that Tina’s time with us was shortened by the failure of the body — the one thing about all of us she had dedicated her life to preserving. First it was Type I diabetes, and then a complicated form of cancer.

The tenacity entered then, and she whipped both — living with the diabetes, and willing the cancer into submission.

There is really no count of the number of events she attended, or the number of student-athletes to whom she attended. But they know who they are. Because Tina was always there, caring and cheering, event after event, malady after malady.

She became famous, far beyond the Forty Acres. Though she never reached 60 years of age, she became a legend in her profession. From the time she left the University of Pennsylvania’s sports medicine arena to come to Texas in fall 1985, Tina was a fixture at Texas, and an ambassador for her trade.

When Texas made its undefeated run to the NCAA Women’s Basketball Championship in 1986, Jody Conradt was quick to note that Tina’s arrival had coincided with the team’s success. She used all of her medical knowledge to help athletes stay on the court, just as she prepared them for a healthy life beyond the game.

When she realized one of the Longhorns basketball players struggled with an allergy to milk products, she made sure pizza wasn’t on her diet. She came into a world where women were just beginning to grow bigger, faster and stronger, and she nurtured and studied to understand, and to help them understand, this brave new world into which they were moving.

You can pitch in all of the available adjectives to describe Tina, and you would be right. She did have a quiet, gentle touch — patiently kneading the hand of a stroke victim, searching for electrodes that would fire and bring a finger to life. She could be relentless, and she could be firm. But beneath all of that, she was kind. You loved Tina Bonci, because she loved you. It came from inside that tiny body, and it radiated through flashing eyes.

She was on the cutting edge of the modern world of sports medicine. She respected the past, and those in her field who had come before, but she understood that there were new and better ways to treat, and she wasn’t afraid to explore. In that way, she was not only a pioneer, but a pathfinder.

As the decade of the 2010s arrived, Tina’s life took a turn that all of her training and knowledge couldn’t conquer. The cancer had returned, and doctors told her there was nothing more that they could do. It was then that she took a step back, and resolutely faced a future she knew all too well would not be what she, or any of us, would have wanted.

She had earned her place where just a few women were beginning to emerge in her youth. She had defied odds in her profession, and even had withstood challenges of health for her and for her hundreds of patients. Gallantly, she now faced the one thing she couldn’t whip.

When Texas played basketball in West Virginia, Chris Plonsky, Jody Conradt, and long-time friend Becky Marshall visited Tina at her brother’s home in Pittsburgh. There they laughed and enjoyed a great Italian meal. Then they said goodbye. Friday, just a few hours before the Texas women’s team defeated Oklahoma in the quarterfinals of the Big 12 Conference tournament, Tina lost her final battle.

09.02.2005 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The colors

Saturday’s game in DKR-Memorial Stadium, perhaps more than any in recent times, will be a blend of color.

On one hand, there is a celebration of “Texas Orange,” the burnt orange pigment so associated with Texas Longhorn athletics, and The University of Texas at Austin.

On the other, there is the red, white, and blue of America, as compassion, fierce determination, and pride swirl across a green football field with a message of unity.

And all of it will come together for the simple flip of a coin.

Long before the tragedy of Katrina, the Texas-Louisiana-Lafayette game was chosen as a tribute to the past history of Longhorn football. To honor all of those who had played football at Texas, the team of 2005 chose to wear what are called “retro uniforms.”

Chances are, you have heard the stories about how the burnt orange of Texas football came to be. And chances are, those stories are wrong.

Prior to the season of 1928, a young Texas hero named Clyde Littlefield was in his second year as head coach of the Longhorn football team. Littlefield, who had established himself as one of the greatest players in school history during the era between 1912 and 1915, was already becoming known as an innovator.

As track coach, he had started the Texas Relays, and he was trying to build on the tradition he and some other greats of the early 20th century had begun.

That was when Littlefield zeroed in on the color of the Longhorn jerseys. Until then, Texas had used a bright orange, and in the days of the soap suds and the wash boards, the color would gradually fade to yellow.

In fact, the color would look so faded, opponents began using the derogatory term “yellow bellies” to describe Texas.

The well-traveled Littlefield sought help, and he went to a fellow named O’Shea at the O’Shea Knitting Mills in Chicago. Littlefield told O’Shea about the problem, and his friend promised he would work up some different colored yarn.

“When you get the color of orange you like, we’re gonna establish it as your orange,” Littlefield remembers O’Shea as saying.

And that is how “Texas Orange,” the dark orange color known throughout the sports world as “burnt orange,” came to be…but the story has a postscript.

The dye which O’Shea used to create the color came from Germany, and during World War II, the supply obviously was stopped. So Texas went back to a lighter color.

When Darrell Royal came to Texas in 1957, he began seeing pictures of the past where the Longhorns wore a unique orange. He asked his friend, Rooster Andrews about it, and he did some research. Rooster was able to find the exact color which O’Shea had created, and duplicated it.

And that is how, in 1962, Royal changed the Longhorn football jerseys back to “Texas Orange.” Other Longhorn teams followed, and Saturday night, the 2005 team pays tribute to the era of the early 1960s by wearing “retro uniforms.”

When Texas first changed the jerseys, because Royal was known for favoring the running game, there were those who thought he did it as a deception, to match the color of the football…and it is true that from 1962 through 1964, Texas won 30 games and lost only two.

Fact is, however, that half of those victories came on the road, when Texas wore solid white uniforms. But what we know is, some folks never let facts get in the way of a good story.

In recognition of that early 1960s era, Coach Darrell Royal and the two surviving tri-captains of the team–David McWilliams and Tommy Ford–will be honorary captains, and meet at midfield with the officials and the captains of the Ragin’ Cajuns.

And that is where the second part of our story comes in.

Throughout the game, there will be an emphasis on helping the victims of the storm which devastated the Gulf Coast region. All of last season, including in the Rose Bowl against Michigan, Texas was led on the field by Ahmard Hall, a Marine veteran, carrying the American flag.

Saturday, those honors will go to senior Karim Meijer, a special teams player with a 3.9 GPA who earned a football scholarship this fall.

The flag he will carry was given to the team on Thursday by Nathan Kaspar, a 2001 Longhorn letterman who flew the flag as a Navy helicopter pilot on missions over southeastern Iraq.

Meijer is carrying the flag because Hall has been chosen to represent the team as its captain at the coin toss.

In such troubled times, where Americans are in harm’s way for different reasons worlds apart, it seems an almost incongruous blend, this weaving together of football tradition and the flag of The United States of America.

But what we will celebrate Saturday night is the people, the players of the Burnt Orange and the people ofThe Flag.

As our servicemen and women fight terrorists who would threaten our freedom, damaged souls struggle to put the pieces back together from an unthinkable tragedy.

We are told that 11,000 refugees from New Orleans are now housed in the Astrodome in Houston, and Thursday night, for a couple of hours, they were able to put aside their troubles and find relief from a televised football game featuring the New Orleans Saints.

Some years ago at a seminar on “Integrity in Sports” held at the LBJ Auditorium, the question was asked, “Why does sport matter so much?”

The late congresswoman Barbara Jordan answered, and this is what she said:

“Why does sport matter so much?”

“It matters because sport is vital, it is viable, it is basic, and it is essential. Sport is not a frivolous distraction as one may first, without thinking, believe. Sport is an equal-opportunity teacher. It is a non-partisan event. It is universal in its application.

“I see sport as an antidote to some of the balkanization that we see occurring in our society; everybody wanting their own private little piece of turf; an absolute abandonment of any sense of common purpose, of common good. It is almost a cliché to say there is no `I’ in the word team. If you are so focused on self, you cannot have any awareness of the common good.

“Another reason why I believe sport is essential is self-esteem. In order to be a contributor to American life, each individual needs to have a high regard for himself or herself first. Sport can do that. If you get out there and you have never been recognized for anything before in your life, if you show some capability, some particular tilt and talent for a sport, it gives you self-esteem.

“I believe that sport can teach lessons in ethics and values for our society. It is attractive to the young, and how many times have we heard someone despair over the plight of our young people.” If you give them something to engage their energies, you would see that it might be something which lures them into the community of mankind and womankind.”

Mack Brown has asked all Longhorn fans who will attend the game to give to established agencies so that help can be sent to the victims immediately. He also asked people of faith to pray.

Barbara Jordan probably would have done the same. But on Saturday night, her words about the purpose of sports ring.

This is why we will play.