Bill Little Articles part XI

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

Looking Back

-

Almost Heaven

-

The Final Four

-

Teamwork

-

And the Band Played on

-

The Second Season

-

For Love of Game

-

Streaking into Dallas

-

Being James Street

-

Kipling, Football, and the Longhorns

-

About the Ribbons

02.27.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little commentary: Looking back

Integrating athletics at The University of Texas at Austin.

l Little, Texas Media Relations

In celebration of Black History Month 2014, it is appropriate we take a look back at the journey as far as University of Texas athletics is concerned.

For reference, the most significant events came 50 years ago in the 1960s, when the UT Board of Regents cleared the way for black athletes to participate in varsity sports at The University.

The pathfinder from that era was James Means, an Austin native and high school track athlete. Means enrolled as a student at UT in spring 1964 when the Southwest Conference, as well as UT, took an affirmative step to allow participation in athletics for all eligible students.

On Feb. 29, 1964, Means participated in a track meet at Texas A&M as a member of the UT Freshman team — in the days before freshmen were eligible to participate with the varsity. In 1965, he became the first black athlete in the Southwest Conference to earn a letter. He went on earn three letters at Texas before graduating in 1967.

About the same time, a young man named John Harvey was etching his name in Austin history as perhaps the greatest athlete ever at the original Anderson High School. Anderson had remained an all-black school on the east side even though Austin’s schools had technically been integrated since the mid-1950s.

Harvey actually signed a letter of intent to play football at Texas for Darrell Royal. He never entered UT, choosing instead to go to Tyler Junior College, where he became an All-American and later a star in the Canadian Football League. In the fall of 1968, a linebacker from Killeen named Leon O’Neal became UT’s first black football recruit to participate, playing as a freshman.

O’Neal had left school by the time Julius Whittier signed and enrolled as a freshman in 1969. Whittier, who was inducted into the Longhorn Men’s Hall of Honor last fall, lettered in the seasons of 1970 through 1972.

Other pioneers included Sam Bradley, who was the first black men’s basketball letterwinner in 1970, and Andre Robertson, who lettered in baseball as a freshman in 1977 — before going on to a career that included starting shortstop for the New York Yankees.

Royal made a strong statement in 1972 when he chose Alvin Matthews, a NFL star with Austin roots, as the first black assistant coach at Texas. Matthews, who was playing for Green Bay at the time, had been a star at Texas A&I (now Texas A&M-Kingsville), and was a product of Austin High.

Matthews served dual duty for two years, spending time at Texas in the off-season and reporting to Green Bay, until it became clear that his success in the NFL would keep him in the league longer than anticipated, and he gave up the Texas job.

The first black head coach at Texas was Rod Page, who led the UT women’s basketball team to almost 40 wins in two seasons in 1975-76 and 1976-77 until turning the program over to Jody Conradt.

It has been 50 years since James Means changed the face of UT Athletics, but in truth, the powerful legacy of the contributions originally manifested itself more than 100 years ago.

Emerging from the early days of Texas Football was perhaps the most interesting character in The University’s young history, and he wasn’t even a player.

He would dress in a black suit, with a black Stetson hat, and he touched more football players — with his hands and with his heart — than any man in the first 20 years of Texas Athletics.

Henry Reeves was a special kind of pioneer. He was born April 12, 1871, in West Harper, Tenn. He was the son of freed slaves, a black man who would set forth to make his mark in a new world of freedom.

No one knows when he came to Texas, but he was a fixture in athletics almost from the beginning. He carried a medicine bag, a towel and a water bucket.

In fact, Henry Reeves became almost as well known as the team itself. The cries of “Time out for Texas!” and “Water, Henry!” brought the familiar sight of his tall, slender figure quickly moving onto the field. There he would kneel beside a fallen player, or patch a cut, or soothe a sore muscle.

“Doc Henry” he was, and in the 20-plus years from 1894 through 1915, he was a trainer, masseuse, and the closest thing to a doctor the fledgling football team ever knew.

In the 1914 publication “The Longhorn,” he was called “The most famous character connected with football in The University of Texas.”

“He likes the game of football, and loves the boys that play it,” they wrote.

But who was this man? Where did he get his knowledge? How did he earn acceptance and respect?

You can look at the pictures and see a mature, studious face — a man whose skills and understanding were obvious. It is likely, folks surmised years later, that Reeves had been trained as a doctor at some of the historically black colleges of the time, and had worked in segregated hospitals.

Once, a new athletics administrator tried to dismiss him and the students rose up in protest. Henry Reeves stayed on. The Cactus yearbook listed the all-time teams of the early days, and one team was picked by the coach, Dave Allerdice. The other was called “Henry’s Team.”

As the team boarded a train to go to College Station to play the Aggies in 1915, Doc Henry felt a numbness that all his self-taught medical knowledge couldn’t cure. He went on to the game, but by halftime the stroke that would kill him had paralyzed the lanky trainer so that he could no longer run.

Henry Reeves lingered for two months after the stroke, and the entire student body took up a collection to pay his medical bills. After his passing, the athletics council voted to award his widow a small pension.

When he died, the Houston Post gave him a special tribute. To put it into perspective, in that day, a black man could not attend The University of Texas, nor for that matter, eat at the same table with the men he treated.

“The news of his death will be heard with a sense of personal loss by every alumnus and former student of The University of Texas, whose connection with the institution lasted long enough for him to imbibe that spirit of association which a quarter century and more of existence has thrown around the graying walls of the college.

“No figure is more intimately connected with the reminiscences of college life, none, with the exception of a few aging members of the faculty, associated with The University itself for so long a period of time.

“In the hearts of Longhorn athletes and sympathizers, Doctor Henry can never be forgotten. A picture that will never fade is that of his long, rather ungainly figure flying across the football field with his coattails flapping in the breeze. In one hand he holds the precious pail of water, and in the other the little black valise whose contents have served as first aid to the injured to many a stricken athlete, laid out on the field of play.”

Henry Reeves left the young university a message it would take years to resolve.

It was a message that the color of a man’s skin made no difference in his mind, his skill, or his heart. All are given a chance to make of themselves what they choose.

They are the pioneers — whose legacy we celebrate — and whose memory we honor.

11.10.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Almost heaven

Ever since West Virginia entered the Big 12, the aura of a night game in the mountains has stood as a benchmark for what the college football experience should be.

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. — If you love the game, you had to embrace the night.

College football is not, nor will it ever be, flawless. It is a game played by young people, and it is perfect only in its imperfection. The pages of Longhorns history are filled with great games that are remembered because, in one shining moment or another, Texas overcame adversity and triumphed — games where the spirit conquered the odds; where will superseded what seemed the inevitable.

Saturday evening in Morgantown was one of those moments.

Ever since West Virginia entered the Big 12, the aura of a night game in the mountains has stood as a benchmark for what the college football experience should be. When the big screen in the stadium darkens as night comes in the Southern Appalachian Mountains where the Monongahela flows toward the Ohio, you are welcomed to the ominous coming of a “Night Game” to Milan Puskar Stadium.

And they came, almost 60,000 of them, to see Texas play their beloved Mountaineers. But a funny thing happened as the Longhorns got their first taste of a road game in West Virginia — they found a passionate fan base that, for the most part, included good God-fearing people who were there to cheer for their team, rather than to simply cheer against Texas.

Saturday night in Morgantown, Texas found a cradle of folks who embrace the game, love their state, and cheer loud and long for their team. The fiber of the people and the rich heritage of the land — that space where the history of the mountains far outdates football and rivalries — overrides the few who are prone to be rude. This is a place where the Mountaineers mascot sought out Nate Boyer after the Texas Green Beret deep snapper carried the flag on the field to thank him for his service to America.

In the midst of that setting, after a first half that neither team would be proud of, a second half of college football for the ages emerged. Lackluster statistics and mistakes gave way to a serve-and-volley, lead-swapping game where big plays countered big plays until it ended with a 47-40 win for Texas in Mack Brown‘s first-ever overtime game.

It was, after all, a triumph of positive energy. Down 19-13 at halftime, Texas would trail 26-16 with only a quarter and 7:26 of the third quarter remaining. Before that third quarter ended, Texas had taken a 30-26 lead. But the zaniness of the evening was only the beginning. West Virginia took a 33-30 lead with barely a minute gone in the fourth quarter. Texas answered with an 11-play drive that ate almost five minutes off the clock and led, 37-33.

Three plays later, the Mountaineers connected on a 72-yard touchdown pass against an all-out blitz and it was 40-37, West Virginia. The “serve break,” to use a tennis term, came on the next two series. Texas went three-and-out and with less than three minutes remaining, the UT defense stopped the Mountaineers on a crucial third-and-one and forced a bad punt. With only 2:35 remaining, Case McCoy and his Longhorns offense were in a familiar position. They had to come from behind.

McCoy had become part of Longhorns lore when he led his team a to a game-winning field goal against Texas A&M in College Station in 2011. He had come off the bench and rallied the Horns to a season-saving victory over Kansas in Lawrence last year. This season, he had driven Texas the length of the field and scored on a quarterback sneak to beat Iowa State in Ames.

Now here was Texas, at its own 36-yard line trailing by three points at 40-37. Working with co-offensive coordinator and play caller Major Applewhite, Texas and McCoy used the running and pass receiving of Malcolm Brown to drive to the West Virginia 47-yard line. In pregame, kicker Anthony Fera had had the distance heading toward the north goal from the opponent 40. His longest kick has been 50. But none of that mattered when McCoy’s second and third down passes went incomplete.

It was fourth down. Fifty-nine seconds remained in regulation. Texas called timeout.

Watching on television more than 1,000 miles away, a learned, veteran college coach saw something he liked. While other coaches may appear tense and tend to be stern and rant in that moment, Mack Brown was laughing.

“I will tell you this,” said the observer. “Texas won that game because of Mack Brown. The team reflected his positive attitude.”

Facing fourth and seven, he looked at his senior quarterback and laughed.

“You’re going to do this again,” he said smiling.

And Case McCoy went out and threw a pass to Jaxon Shipley — just as he has done thousands of times since the two great friends were kids together, Case in the fourth grade at Jim Ned and Jaxon in the third grade in Rotan. Nine yards later, Shipley had a first down and the Longhorns had new life.

Applewhite came with perhaps the play call of the game on the next play, when Malcolm Brown broke for 27 yards to the Mountaineer 11-yard-line to set up Fera for a game-tying field goal that knotted the score that forced overtime with the score 40-40.

West Virginia won the flip and chose to play defense to start the overtime. Again, it was Malcolm Brown and McCoy with some deft play calling negotiating the 25 yards to score. McCoy’s 14-yard pass to Marcus Johnson carried for a first down to the West Virginia 11. The Horns took the lead on McCoy’s two-yard TD pass on yet another third down play, this time to fullback Alex De La Torre, who caught the first pass of his career in what turned out to be the game-winning TD as the Longhorns led, 47-40.

Still, it would be up to the defense to seal the deal.

Greg Robinson‘s crew had been sensational for much of the game, but hadn’t been able to stop the inspired Mountaineers in the midst of the lead-swapping in the second half. On the first play, West Virginia gained 20 yards to the UT five.

Legend has it that more than 40 years ago, in an epic game against Arkansas when the Longhorns had to have a stop and the Razorbacks were inside the five, all-American linebacker Johnny Treadwell is said to have said “Now we’ve got ’em right where we want ’em.”

And so it was with Texas, 2013.

On the first play, running back Charles Sims gained a yard to the four. On the second, Quandre Diggs knocked away a pass. Steve Edmond did the same on third down. It had come down to one play.

Since Greg Robinson came to Texas following the BYU game, Steve Edmond had been a special project. He saw something he liked, and under his tutelage, the Longhorns have blossomed. The packed crowd held its breath. On the Longhorn bench, Case McCoy knelt, prepared if needed to go back on offense if the Mountaineers scored.

And Steve Edmond picked off the last pass of the game.

Texas players rushed the field. At the distant end, the Longhorn Band played and the loyal UT contingent cheered. The crowd, now silent, stood respectfully as Mack Brown and Dana Holgorsen met and TV cameras converged on Texas.

As the teams mingled with each other, a West Virginia player stood alone near the 30-yard line at the north end of the field. To nobody in particular, he simply said, “Awh…man.”

In the Longhorns locker room, Texas surrounded its injured stars Jonathan Gray and Chris Whaley, and began a chant that simply said, “I play for you…you play for me….”

And that, as the team prepared to head into the night and early morning, leaving the mountains of West Virginia for the Hill Country of Austin, pretty well told the story.

Because college football is, after all, imperfectly perfect. It is about each other, it remains a place where team is defined, not only by the stars, but in those who collectively pull together for the good of the whole. In our world filled with impurities, in that space there is something pure, and that is “joy.”

And that, folks, is about as perfect as it can get.

1.08.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The final four

It is hard to believe that a season which began on Aug. 31 has ticked its way through two thirds of the season.

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. — Texas is down to its final four games of the regular season, and right now the most important is Saturday’s meeting with West Virginia. Because that’s the game that stands between the Longhorns and the “fourth quarter.”

It is hard to believe that a season which began on August 31 has ticked its way through two thirds of the season. Even harder, however, is the unimaginable finish which the Big 12 Conference seems to have in store.

Contenders are playing contenders down the stretch in this league chase, and it is already a nightmare for prognosticators who have wagered a guess as to the outcome.

Mack Brown has always said “they will remember November,” and it would appear he is right. And, they may even remember early December as well. But the fact is, you cannot get to tomorrow without going through today, and that’s where the trip to West Virginia comes into play for Texas.

The Longhorns — with their classy “storm trooper white” uniforms, have put together a remarkable road record in Big 12 competition under Brown. This one is unique in that Texas is making its first trip to West Virginia since the Mountaineers became members of the Big 12 Conference last season.

The ‘Horns are riding a five game winning streak and are tied with Baylor for the lead in the Big 12. Those two teams actually do play in the final game of the season on December 7, but between now and then both teams have a sack full of work to do.

It begins for Texas with the venture into new territory.

The meter is running on the season. The road trip to Morgantown and the December trip to Waco are bookends sandwiching two home games with Oklahoma State and Texas Tech. You can play with the numbers any way that you will…get past West Virginia and two of your final three games are at home.

The challenge, however, is that West Virginia is fighting to salvage a season. A win in overtime last weekend at TCU invigorated what had been a dissatisfying season for the Mountaineers. Still, a 3-1 home record contains a highlight victory over league pre-season favorite Oklahoma State.

Texas will be trying to maintain its impressive run of late. The defense has been the surprise of the league since conference play began, and the offense has been a strong combination of a running game and effective passing.

Now, Texas gets to take its show on the road once again. The ‘Horns won their showdown with Oklahoma in Dallas, and then withstood a three-hour rain delay in Fort Worth to beat TCU. After 42 long days, they finally got to play at home last Saturday, and whisked past winless (in league play) Kansas.

In the movie, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” we have spoken often of the line where the heroes find themselves pursued and the line “who are those guys?” is one of the classics of all of film.

That is the question the Big 12, and to a growing extent, the American college football landscape is asking. Texas, after a 1-2 start, is suddenly a player on the scene again.

Saturday in Morgantown, they will try to keep that going. They have made it to the “Final Four.” Now, they will try to get unscathed into the “Fourth Quarter” — as a 12 game regular season heads surprisingly into the home stretch.

11.05.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Teamwork

As the Longhorns rolled to their fifth straight victory, they would do it with contributions from all phases of the game.

We went all the way to the distinguished Harvard School of Business to determine what happened in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium Saturday, and this is what the esteemed professors J. R. Katzenbach and D. R. Smith had to say about it:

“A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable.”

The book, by the way, is entitled “The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization.” There is probably a comparable one in the McCombs School of Business here at UT, but for the moment we will hang with the Bostonians.

Mack Brown and the Texas coaching staff are into the same kind of thing, and Saturday’s latest example resulted in the sixth win of the season and a solid 35-13 victory over Kansas. And it was the classic definition of a team effort.

As the Longhorns rolled to their fifth straight victory to stretch their Big 12-leading record to 5-0 and their regular season record to 6-2, they would do it with contributions from all phases of the game.

The day, however, had begun with some trepidation from Brown. After emotional wins in a come-from-behind effort at Iowa State, followed by the stunning crushing of Oklahoma in Dallas and a rain-delayed triumph over TCU in Fort Worth, Saturday’s meeting with a Kansas team that is hungry to break its losing streak in league play had all the appearances of a “trap” game.

The Longhorns of 2004 would end their season with a Rose Bowl victory over Michigan, but it would be Vince Young’s famous “fourth and 18” run that would save the game at Kansas. Last season, Case McCoy came off the bench to lead UT to a win in the last 12 seconds against the Jayhawks.

So when McCoy and Chris Whaley exhorted their teammates to play well before the game in the locker room, most of the 97,000 or so fans who showed up on a brilliant Saturday afternoon figured this one was a game of going through the motions.

While Texas offense was still searching for consistency and the defense gave up a long pass just before halftime to set up a field goal, it was 14-3 at intermission.

In the locker room, Brown told his team, “Somebody has got to step up and make a play.” And this time, it would be Chris Whaley and the defense who would do it.

It was almost two thirds of the way through the third quarter, and Kansas had notched a field goal on their opening drive of the half. After missing his first two punts in uncharacteristic fashion, Anthony Fera had gotten off a 46 yard punt with 6:37 remaining in the third quarter. The Jayhawks were trailing by only eight points, and when a Longhorn defender ran into the kick receiver, a 15-yard penalty appeared to swing momentum to Kansas.

But on the next play, Jackson Jeffcoat turned the quarterback into Cedric Reed, who knocked the ball loose as he tackled him. The ball bounced free, and on one hop, Chris Whaley picked it up and ran 40 yards for a touchdown that effectively put the game on ice.

The play ignited the Longhorns, who went on to dominate the rest of the game. In the fourth quarter, Texas rushed for almost 100 yards as running back Malcolm Brown finished the game with 119 yards on 20 carries and four touchdowns.

What was impressive about the game, and the point underscored by the definition of “team,” was the number of players who stepped up with significant plays. You could pick a name, and at some point in the game, that particular player would have done something to make a difference.

The growth of the team over the past five games is also reflected in the work of the coaches. While Greg Robinson and the defensive staff have justifiably received a lot of credit, Major Applewhite and Darrell Wyatt and the offensive staff have also retooled an offensive attack completely.

What emerged Saturday was a strong showing on both sides of the ball, although the defense was more consistent than the offense.

It all broke open with Whaley’s fumble return for a touchdown. It was the spark the team had been looking for. Where the Oklahoma game may have been highlighted by touchdown strikes from McCoy to Marcus Johnson and Mike Davis, and TCU was impressive because the Horns didn’t show a letdown after OU, the Kansas game was the game where Brown anticipated a possible “trap.”

Where there have been seasons where teams search for identities, this one for Texas is unique. On both sides of the ball, what was once…isn’t. And what has evolved is impressive.

Now, Texas has four games left in the regular season. Call it “the final four,” if you will. The upcoming trip to West Virginia explores new territory for any Texas team. But the one message this team seems to have gotten from all that has transpired is you truly do have to take one step at a time.

In so many ways, the season has turned from one where some media and fans had all but given up on this team to one of fun and excitement. And the reason it has worked? They never gave up on themselves.

There are so many story lines here that it is impossible to know which one to follow. It seems with each play or player, there is something special to tell.

Saturday was another installment in a play or a movie. It is like a musical arrangement, where soloists pop up at any time, and carry the piece for a while. You often have no idea from where or from whom it is coming, but it is there…it’s really there.

What they have done, these Longhorns of 2013, is put fun back in the game. And wherever they are going or wherever they wind up, it is a pretty cool ride along the way. They are playing, most of all, for each other. And when you get that, here is what you have:

“A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable.”

And that’s not a bad deal at all.

10.29.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: And the band played on

The team, spirit groups and the band had just experienced something that they can tell their grandkids about.

It was the season of 1968, and Darrell Royal’s Texas Longhorns were desperately trying to fight back against a Texas Tech Red Raider football team on a dreary September night in Lubbock.

Coming off a 6-4 season in 1967 and a season opening tie to Houston, the Longhorns were woefully short on crowd support. Travel to road football games was a bit rare at the time, particularly to a South Plains outpost like Lubbock.

As athletics director (and the guy in charge of funds for athletic events), Royal had chosen not to spend the money to take the Longhorn Band to the game. After returning to Austin following the Horns’ 31-22 loss, he openly regretted that decision.

“I kind of like to hear ‘Texas Fight’ when we have a rally going,” he said.

And then he met with his great friend, Longhorn Band Director Vince DiNino, and vowed never to travel without the band again.

Saturday night in Fort Worth, that mutual commitment was put to the test in a big way. The entire Longhorn band, 390 members strong, was on hand in Fort Worth for what was to have been a showcase halftime performance. They were even beginning to make their way toward the field when, with 6:08 remaining on the clock, the game was stopped due to lightning and the teams were sent to the locker rooms.

Band members scurried under the newly constructed stands at Amon Carter Stadium, finding what space they could in concourses and stairwells, as the storms came in. For over three hours, and without much information, they waited.

“They just hung out together,” said Dr. Rob Carnochan, the band director.

The Longhorn football team was in the midst of its own waiting game. Having gone through a bad experience in Provo, Utah, when the Brigham Young game was delayed at the start, Mack Brown was determined to handle this one differently.

“We told the players to take off their pads, meet with their coaches, and do whatever would make them comfortable. Whatever they did at BYU, we told them to do something different,” he said. Some players listened to music, others napped, others found ways to entertain themselves. Most of all, they continued that bond which has been evident in this team since the beginning of the season. Together, they determined, they would handle this.

Realizing that it had been a long time since the pre-game meal at 2:30, staff dietician Amy Culp, trainer Kenny Boyd and football strength and conditioning coach Bennie Wylie, began working their own version of the Biblical “loaves and fishes” story. They took the chicken from boxes which had been delivered to the dressing room for the postgame snack and divided it in half. The players needed “fuel,” true enough — but they wanted to make sure they didn’t stuff themselves.

The coaches used the break as they would have used a half-time intermission. They could meet and talk about adjustments, but by rule they could not use television or any other photographic images to enhance their points.

Of all of the entities surrounding college football, perhaps the cheerleaders top the list of unique. Their shared interests in their trade actually brings them a bond and a friendship which often isn’t found in other areas. While the team members were trying to keep themselves occupied and the band was trying to stay dry, the Texas Cheerleaders and Texas Pom had hooked up with their counterparts from TCU, who had taken the UT spirit groups into nearby Daniel Meyer Coliseum—where they actually posed for pictures doing double stunts together.

When the weather finally cleared after a more than three-hour delay, everyone got the word to return to the stadium. Not surprisingly in such a fluid, confusing situation, communication was excellent between the officials and the teams, but random in the other groups.

“There were a lot of rumors,” recalled Carnochan, as to the form in which the game would continue. Eventually, the decision was to finish the final 6:08 of the second quarter, and then break for five minutes (with the teams remaining on the field) before starting the second half. That window was eventually shortened to just three minutes. At any rate, the halftime show the band had worked on so intently wasn’t going to happen.

But when the Longhorns emerged from the locker room, the energy was obvious. Whatever had happened at BYU, it was clear this group was re-entering the arena with a purpose. And the band played “Texas Fight.”

“There may not be anybody there,” Brown had told his players. But happily, to his amazement, he was wrong. There in the stands was the Longhorn band, in full uniform and blasting away as the cheer and pom helped lead the team back on the field. Some Longhorn fans had even made their way to the general admission area behind the Texas bench, which had been vacated by TCU students.

In one of the strangest football games a Texas team has ever played, the Longhorns won their fourth consecutive Big 12 game to remain atop the league standings. They did it with solid kicking from Anthony Fera (three field goals and a 40-yard punting average), a balanced offensive attack which continued to feature the run and some precision passes, and a stifling defense which has now allowed only two offensive touchdowns in its last two games against TCU and Oklahoma.

When the Horns closed out their 30-7 win and at some point well past midnight headed to the north end of the stadium to salute the band when it played “The Eyes of Texas,” the game was over. The trip home would last another five or six hours for the band, while the team’s flight home would land just a little past 4 o’clock.

On Monday, football equipment manager Chip Robertson was working on putting together a gift from Mack Brown and the team to the band and the spirit groups.

For everyone, it was a memory. The team, spirit groups and the band had just experienced something that they can tell their grandkids about.

Most of all, in an environment where far too many people are into the “I” factor, these young people proved the special importance of doing something together. You don’t find that very often, in a society driven by the Balkanization of so many things.

But on that night in Fort Worth, and the morning which came quickly behind it, there was a capsule of a moment where being a college kid carried a camaraderie that too often is far, far away. It is a part of the college experience that is to be treasured, even if you are hungry and sleepy, on the long drive home.

Vince DiNino would remember why that all makes sense, and Darrell would be happy to pay that bill.

10.25.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The second season

Seldom in life do you get a chance to start over, to put away the past and, like an artist, paint on a clean canvas.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

FORT WORTH — The track record for Mack Brown teams following a victory over Oklahoma is pretty astounding. Consider these:

1998: Went 5-1 (only loss 42-35 to Texas Tech), won the Cotton Bowl.

1999: Won the Big 12 South, going 4-1 over the finish of the regular season (only loss 20-16 to Texas A&M). Played in the Cotton Bowl.

2005: Went 8-0, won the Big 12 South, the Big 12, and the BCS National Championship.

2006: Won four straight and ranked No. 3 nationally until QB Colt McCoy was hurt against Kansas State and Texas A&M. Finished the year with an Alamo Bowl win over Iowa.

2008: Won six of seven, only loss in last second to Texas Tech. BCS Bowl win over Ohio State in the Fiesta.

2009: Won seven straight including Big 12 Championship, only loss to Alabama in the BCS National Championship game when Colt went down.

In short, three of the six teams played in BCS Bowl games, winning the National Championship and the Fiesta Bowl. Two played in the Cotton Bowl. One in the Alamo Bowl.

The exhilaration that the Horns enjoyed last week following the victory over Oklahoma has given way this week to focusing on their next opponent, and — more importantly — focusing on themselves.

As we said last week, the victory over Oklahoma proved what the Longhorns CAN be. Now, against a worthy opponent in TCU, they get to find out what they WILL be as Texas makes its first trip to Fort Worth since 1994.

In the first-ever meeting between the two schools as Big 12 members last year in Austin, the Horned Frogs derailed a Texas team which was on a late season roll with a 20-13 victory. Saturday in Fort Worth, TCU has a chance to salvage its 3-4 season with a win over the old Southwest Conference rival.

The vision of a future which Texas saw two weeks ago in Dallas reflects the optimism of what has turned out to be a perfect break to begin a “second season.” The Longhorns, at 4-2 overall, are 3-0 in the Big 12 with six league games remaining. To emphasize the point, think of a staircase where you have to take steps upward one at a time. That is the direction for Texas.

The hopeful end result may be a Big 12 title and a BCS bowl trip, but as sport is a reminder of life, you can’t get to the top of the mountain by keeping your eyes only on the finish. How many times have you not paid attention to a single step and stumbled because you looked too quickly ahead on a precarious journey?

That’s why this game Saturday is every bit as much about the mental approach as it is the physical. Both Texas and TCU have good players, and traditionally this seems to turn out to be a tough battle. The game of football in the Southwest didn’t just start with the Big 12 — the history between these two schools goes back more than a century.

The surprise that the Frogs pulled off last year was not something new. Traditionally, this matchup always seemed to come just before the Longhorns finished their season against archrival Texas A&M, and often TCU — even when they had a lesser team — presented a significant challenge.

This time, TCU is actually favored, although the Frogs are battling for victories to get to a bowl, and Texas is hoping (as has usually been the case) for greater things.

What this one comes down to, as Mack Brown and his staff have reminded the team all week, is individual accountability. Teams thrive and fail on that single factor. You do have to rely on the “man on your right and your left,” and you do have to be accountable to the “man in the mirror.”

Saturday is particularly important for this Texas team, which is excited about where it is headed, and yet cannot assume anything. The Big 12 this season is the most balanced league the Longhorns have been a part of since the glory days of the old Southwest Conference, when anybody could beat anybody.

Seldom in life do you get a chance to start over — to put away the past and, like an artist, paint on a clean canvas. That is where Texas finds itself.

And, like a painter, you have to brush colors into a background before you can finish the work. It is a puzzle, where you interlock a core, and build from there.

Saturday won’t decide the ending, but it will determine the direction.

10.14.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: For love of the game

In the end, this stop on the road in the middle of the 2013 season was, plain and simple, about “team.”

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

DALLAS — As he sat in the Longhorn Network studio and talked with LHN’s anchor Lowell Galindo a couple of weeks ago, Case McCoy spoke about a summer of searching. He had traveled 3,000 miles and spent ten weeks in the country of Peru.

But unlike those who in a time past sought wealth and treasure on such an excursion, Case McCoy was looking for something different: he was trying to find himself.

“My life had been about me and about football,” he said to his dad. “I just decided that I wanted to do something for somebody else.”

In that interview, he reflected on the people he had touched — and those who had touched him — and he said this:

“I was just going through the motions here. I had lost my passion and I came to realize how much I loved this game, and there was a role that I could fill with my brothers on this team. I know that things haven’t always gone well for me, and the Cinderella story that I had dreamed for myself never happened….”

And so it was that on a hot, humid day in Dallas with over 90,000 people watching and millions more tuned in on television, Cinderella arrived at the ball — surrounded by friends that formed a cast of characters which body slammed their way straight into the finest moments of a series full of characters, and fine moments.

Kevin Costner did a baseball movie a few years back which perfectly fit the moment. He called it “For Love of the Game.” There is truth in that, and it does take a commitment from players who are willing to pour themselves into the moments that transpire in the arena.

Saturday, however, was about far, far more than that.

Because to understand what happened in Dallas in the storied old Cotton Bowl Stadium, you first have to understand the people. The legendary attorney Joe Jamail talked to one of Mack Brown‘s first teams, and his subject was success. To boil it down and sanitize the language a bit, this was the gist of what he said:

He told them he had won more lawsuits and more money than anybody in that business, and he talked about the people he had faced on the other side of the courtroom. Then, he talked about a necessary key ingredient in any kind of competition — pride.

“If come up against me and you have pride,” he said, “then you’ve got a chance. If you don’t, I will whip you every time.”

Saturday’s 36-20 victory over Oklahoma was vindication for a maligned football team, true enough. Passion, pride, love of the game – all of that mattered. But for the Longhorn family, it was something bigger than that. It was a win for a coaching staff, and it is important to understand why.

Coaches, in the purest sense and at every level, are never in this business for money. Those who are do not last long. Coaching is like being a farmer. You work hard every day of the year dealing with elements which you ultimately cannot control. You teach, nurture and hope. Ultimately, growth and maturity are the things that you cannot make happen.

But when it does — when that crop comes in on a West Texas farm and when players rise to, and beyond your expectations — there is the reward for a coach. You take pride, not in what you did (although that is certainly justified), but in what they did.

You celebrate the victory because half of the 90,000-plus people in the stadium are screaming and crying for joy. You deserve to take a moment to appreciate what you accomplished with a brilliant game plan and long hours in the office and on the practice field. Most of all, you gain your strength because, right before your very eyes, when the critics critiqued and the fans doubted, your players learned, and they — even if nobody else seemed to — believed.

Rival games carry with them commitment – and that is what Texas got from its entire football family. And while much of the limelight will be shared by Mack Brown and the players, every single person -from the student managers and trainers to the players who mirrored Oklahoma in practice – contributed to this one. That, as much as anything, is the definition of the team’s theme of “For the man on my right and the man on my left.”

The expanded football staff includes some really bright young people as well as veteran coaches. There are graduate assistants and quality control personnel who spend hours working with the full-time coaches. They have come from small schools and traditional powers, and all share a respect for Mack Brown and The University of Texas. As the Cotton Bowl turf filled with orange after the game and sweat and tears of happiness mingled with photographs and magic moments with the band, cheer, pom and service organizations, the smiles on the faces really did put special meaning in the phrase “The Eyes of Texas.” The band played, the fans stayed, cheering as the players took turns wearing the Golden Hat — the trophy that goes annually to the winner of the game.

When the celebration was over, Case McCoy trotted toward the sideline where the Texas bench had been. There, he shared a private moment and a long father-son hug with his dad, Brad, who had made his way to the field after everyone had left. Major Applewhite, whose game plan Case had executed to near perfection, soon joined them.

The press conference after the game would feature the seniors – guys like Jackson Jeffcoat and Chris Whaley from the defense, Mason Walters and McCoy from the offense. They accepted the praise for their 3-0 start in the Big 12, but quickly pointed out that there was still much more to be done. At 4-2, Texas is on a quest to run the table with its remaining six Big 12 games and win the BCS Bowl berth that goes to the league champion.

That means that you can’t stop here. It is true that the moments and the memories of Saturday in Dallas will last a lifetime. But when Mack Brown was asked what he was thinking about, he said, “TCU.” The Horned Frogs, of course, are Texas’ next opponent. The luck of the draw does give the Horns some time to take in their victory over the Sooners, since next Saturday is a bye week on the schedule.

The Longhorns are halfway through their season. The circle of unity has tightened, and when the TCU trip comes on October 26, their goals to finish strong are still intact. On Saturday they put together a game showing what they are capable of.

Chris Whaley said he dreamed of making a big play against the Sooners, and he did – with a pass interception for a touchdown from his defensive tackle position. Case McCoy said he didn’t sleep a wink on Friday night. Together with their teammates, they went out and made Texas Longhorn history with one of the best team performances in the history of the Texas-OU series.

They answered the critics who wrote them off, and they gave an affirmative answer to those who questioned “Can they?” and now they have converted that to “Will they?”

In the end, this stop on the road in the middle of the 2013 season was, plain and simple, about “team.”

And whether you are Cinderella or a superstar or just somewhere in between, together you can go a long, long way.

10.11.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Streaking into Dallas

The Texas-Oklahoma series goes in streaks. Always has. Always will.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Okay, gang. Let me say this one more time: the Texas-Oklahoma series goes in streaks. Always has. Always will.

So as the pundits stew and the faint of heart wring their hands and predict the sky is falling, worry about something else. Hopefully, world peace and a little bit of rain may actually be more important than trying boldly to predict how Saturday’s game between Texas and Oklahoma will turn out. Because only the players will decide.

Just to make the point, here you go:

1940-47: Texas wins 8 straight.

1948-57: Oklahoma wins 9 of 10, including six straight.

1958-70: Texas wins 12 of 13, including eight straight.

1971-75: Oklahoma wins 5 straight.

1976-84: Texas is unbeaten in 7 of 9 (including two ties).

1985-88: Oklahoma wins 4 straight.

1989-99: In 11 years, Oklahoma wins only two games as Texas is 8-2-1, including 4 straight (’89-’92).

2000-04: Oklahoma wins 5 straight.

2005-09: Texas wins 4 of 5 games.

2010-12: Oklahoma has won 3 straight.

And Coach Royal told Coach Brown that streaks end when one team gets tired of hearing about it, and is good enough to do something about it.

Fact is, if you want to look at the most enlightening numbers of the lot — in the last eight meetings, the series is even at 4-4. And for a game the world considers “a bowl game at mid-season,” that balance is the most representative number of all. The two teams met first in 1900, and Texas holds a 59-43-5 series record and a 47-39-4 edge in Dallas.

Given that I have covered at least one of these two teams every year since I was a student at Texas in 1961 — having spent two years covering the Sooners with The Associated Press in Oklahoma City in 1966 and 1967 — there are some other givens about this series.

First, the game creates heroes. The legacy of the All-Americans, Heisman winners, and those who flash forward from obscurity into the sun on the floor of that storied old Cotton Bowl Stadium are legion. Second, it is a game which creates indelible memories — pictures which will hang in the chambers of the mind forever.

Most of all, the Texas-Oklahoma game — which has become known as the Red River Rivalry — is like a kaleidoscope of tastes, sights, smells and sounds. It is a game of streaks. And it is a game of momentum. There is an indefinable ebb and flow which traces the pattern of the game. The coaching staffs are both really good and both teams have good players. Coach Royal said long ago that this game always comes down to two things — turnovers, and the kicking game.

I remember years ago when our great Longhorns pitcher Burt Hooton was talking to a friend about the man’s son. He was telling Burt — who had just been the outstanding pitcher for the L.A. Dodgers in the National League Playoff series — about his son’s talent. That was when Burt stopped him and asked this question: “But,” he said, “does he have a passion for the game?”

And as these two teams head to Dallas, it doesn’t matter what the critics or the fans — or perhaps even the coaches think. Because this is a game about passion — who has the greater passion for the game?

One of the treasured possessions in Mack Brown‘s office is an old book with a fading blue cover about football. It was written by D. X. Bible, and is signed by both Coach Bible and Coach Royal.

In it, Bible talks about the game, and the fact that it is a hard game. You have to, he said, have passion to play it.

That is what the meeting in Dallas Saturday morning is all about. Bible said the most important thing about football is that it is a team game. More than 50 years before Nate Boyer came up with the theme of this 2013 team of playing for each other, Bible made that point in his book.

This, by the way, was a man who was the third winningest coach in the history of the game when he retired. He had won at Texas A&M and Nebraska before coming to Texas to establish the foundation that is the basis for everything that has ever happened in athletics at The University of Texas.

It was Bible’s teams — by the way — that won seven of those first eight games of the streak scenario from 1940 through 1947 that we talked about.

Royal, of course, was one of the few men who had actually been on both sides of the game. He played at Oklahoma, and began his coaching career at Texas after being hired by Bible (who was then athletics director) in 1957. Mack Brown is another. He was an assistant to Barry Switzer in 1984 before taking the head coaching job at Tulane, and began his Texas tenure in 1998.

The mystique of the game is legendary. Players remember “the tunnel” — from whence both teams enter the field. The equally-divided stadium (where Longhorn fans and Sooner fans actually sit side by side at the 50-yard line on both sides of the field), is unique in itself.

Most of all, however, what you have are two teams that come from storied programs which both rank among the winningest in all of college football.

This time, Oklahoma comes in as the favorite. The Sooners are nationally ranked at 5-0. Texas is 3-2, but two of the Longhorns’ victories came in Big 12 play.

If the series has reflected anything, it is that we should expect the unexpected. Games that were projected as close have turned into blowouts by both sides, and those that were thought to be an easy win for one side or the other have turned out to be dogfights.

Most of all, this series has a way of leaving its mark on the players, and it is they who not only determine the outcome, but remain the images to remember.

That is why it is impossible to predict, and it is why as the dawn comes in Dallas, the stadium will fill with anticipation.

Outside the stadium, maybe 100,000 people will gather at the State Fair of Texas to ride the rides and see the exhibits and hope for a blue ribbon for little Johnny’s lamb or Aunt Sally’s pickles. They didn’t write that song in the musical that “Our State Fair is a Great State Fair” because Texas and Oklahoma were playing football.

It is — the game, the fair, the people — all part of Americana. It is the one place on the planet where two schools from two states gather in such an environment to match pride and bragging rights.

And it is in that space that passion comes into play. Because when you play a game you love because you care so much, anything can happen.

And it usually does.

Bill Little Commentary: Being James Street

The happy-go-lucky competitor we knew in college never really left – but he learned a lot since those days when winning was everything.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

“Let me live in a house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by-

The men who are good and the men who are bad,

As good and as bad as I.

I would not sit in the scorner’s seat

Nor hurl the cynic’s ban-

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.”

Rocks in life are funny things. You can throw them; try to budge them; climb them; sit on them; lean on them, and the truth is you come to depend on them.

James Street was a rock.

Phone calls in the early morning hours are never good things. They are either a misdial or bad news. This one was the worst of news.

James Street was gone. Way too soon. Way too sudden. In the flick of an instant, an icon of Longhorns football had passed away without warning.

If you define a person by the people he knew and the things he did, James Street’s was a life well lived by the time he was in his mid 20s. In an era where college football was the nation’s dominant sport, he became perhaps its most famous player.

“He stood out from everybody else because he made clutch plays and he never quit. He was likeable and fun, but most of all, he won. He remains my favorite Texas quarterback of all-time,” said famed author Dan Jenkins, who covered James and the Longhorns team in 1968 and 1969.

“I remember standing with the late Jones Ramsey in the press box as the fourth quarter began in the “Big Shootout” in Arkansas in 1969. Texas was behind, 14-0, and Street scrambled 42 yards for a touchdown.

“I remember Jones saying ‘I had given up…I’m sure glad Street hadn’t,'” Jenkins recalls. History, of course, chronicles the rest of the quarter, where Street led Texas to a 15-14 win and a national championship. Millions had watched as the Horns pulled off the comeback in the season finale of the 100th year of college football.

And with that, James Street became a “rock star” years before anybody ever came up with the phrase. He was at home in Vegas or in New York. He knew Elvis Presley and President Johnson and hung out with pro football players such as Bobby Layne and Joe Namath.

In that space and in that time, “Being James Street” was a pretty cool deal.

As a player, James was the ultimate competitor, and it didn’t matter what the game was, he was in it to win. But as the shock of the morning gave way to the sadness of the day, we get to talk about the man, and not the game.

“Being James Street” has meant a lot of things to a lot of people. As a football and baseball player at Texas, it meant a guy who was there to compete, and to win. And win was what he did. As a quarterback at Texas, he started 20 football games, and the team won them all. Twenty and “0”. National champions. As a pitcher in baseball, he was just about as successful.

With a wicked curve ball that made him a second-team All-American, he was part of teams that went to the College World Series every year he played, and finished in the top four each of his last two seasons.

He was named the Most Valuable Player on the 1969 National Championship football team, and all three years that he played baseball.

Throughout his college career, “Being James Street” had meant leadership, and as a star pitcher and a quarterback, he often led by example.

In June of 1970, with his football career behind him and the College World Series over, James Street’s athletic career ended. Now, it was time for something else. “Being James Street” meant that it was time to figure out what he was going to do with the rest of his life, and to do that, he had to first figure out who James Street really was.

I remember a message the Baptist preacher in Winters, Texas, once brought to my elementary school. He was telling us something that would impact my life, and I know James got a similar message along the way.

“You have to ask yourself these questions,” he said. “They are the same questions your parents will ask you when you go out at night. ‘Where are you going? Who are you going with? And what are you going to do when you get there?'”

What do you do with your life when the shouting and tumult dies?

As a kid, I once put together a book of poems, and one of them was a little rhyme called “Sometimes.” “Across the Fields of Yesterday,” it went, “he sometimes comes to me…the little lad just back from play, the lad I used to be. And yet, he smiles so wistfully, once he has crept within, I wonder if he hopes to find The Man I Might Have Been.”

He had taken charge of a Texas offense in football, he had taken charge when he walked to the mound as a pitcher in baseball.

James Street, star player, had a decision to make. The early years following his college career hadn’t been seasons in the sun. Not unlike many of us children of the 60s, there was a space where the moments were good, and not-so-good. And some were just flat lousy. It had been a spell since “Being James Street” was really fun. Now, he had to take charge of his life.

Do you spend your life living with what was, and wondering what might have been?

Where are you going? Who are you going with? What are you going to do when you get there?

What James Street did was become perhaps the best structured settlement financial advisor in the country. He helped people who had been touched by tragedy find a way to secure their assets so they could live comfortably for the rest of their lives.

“I didn’t know James in the dark time,” a leading Austin attorney told me. “But what I appreciate about him is that he started a company in a business that he really didn’t know a lot about and he learned.

“He learned the business, and he never used his days as a player as a crutch. He used it as an inspiration. It became about his humility, rather than some kind of diseased conceit. He was the best in the business at what he did, and he was a great guy.”

Some parts of “Being James Street” never changed.

The James Street we knew in later years was not only a successful businessman, he was a caring, devoted husband, father and grandfather. The parenting part came naturally. Throughout his career at Texas and beyond, James had no greater fan and supporter than his mother.

Despite an incredible schedule, he always had time for people. His self-deprecating humor fostered his larger-than-life image. He had a way of making it seem, in the moment, that he always had time for you, and talking with you was the most important thing he had to do in his life.

That was true whether you were somebody like a great friend such as Mack Brown, or a struggling fellow traveler who was trying to whip the disease of alcoholism – just as James had done. And he never appeared condescending. Once, at a dinner at in New York, a waiter was taking drink orders. Martinis, cold beer, wine. Finally the waiter came to James, who politely said, “No thanks, I’ve had enough.” He just didn’t say when. James took his last drink more than 30 years ago.

We will remember his friendship, his honesty, his smile, his little bit of a song, his infectious humor and his uncanny homespun wisdom.

The happy-go-lucky competitor we knew in college never really left — he was still a kid at heart — but he learned a lot since those days when winning was everything.

When his son, Huston, was playing for Westlake High School and they had lost to Midland Lee in the football state championship game, James talked to him after the game.

“Were you as prepared as you could possibly be?” he asked. Huston said yes. “Did you give your best effort on every play?” Again the answer was yes.

“Then,” James said, “you have done everything you could to win, and the other team was better that day. Go over there and shake hands and give them the credit.”

“Credit” was something James never took for himself. In his time at Texas, it would be about his teammates. As a businessman, it was about the people in his company, The James Street Group — one of the largest structured settlement firms in America. When it came to raising kids, it was about his wife, Janie. He was one of the most giving people — of his time, his talent, and his money — I have ever met.

Sunday James and Janie had returned from a trip to San Francisco to see Huston’s team — the San Diego Padres — play the final game of their season. He was proud of Huston’s sports career, but equally proud of his oldest son Ryan (a successful Austin architect), and the younger brothers — the twins Juston and Jordan — and the youngest, Hanson. Daughters-in-law and grandchildren also arrived to make a huge impact in his life.

In the summer of 2002, when Huston was a freshman, the Longhorns won the College World Series, and by chance the Street family joined us at an Omaha restaurant called “Mr. C’s” after the game. We put the NCAA championship trophy at one end of the table as the food arrived, and each youngster waited patiently for all to be served. Then, they held hands and said a prayer, giving thanks for the food, and the day.

And that is the image we are left with. In a very real sense, he was larger than life. But for those who knew him and whose lives he touched, “Being James Street” meant a friend who could lift your day.

That is why that poem at the beginning of this commentary seemed to matter so much.

“Let me live in a house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by-

The men who are good and the men who are bad,

As good and as bad as I.

I would not sit in the scorner’s seat

Nor hurl the cynic’s ban-

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.”

It defines him, it validates him. Because that’s what being James Street was really all about.

09.27.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Kipling, football, and the Longhorns

Without even realizing it, the Texas Longhorns had lived out the words of some of the lines that Rudyard Kipling had written all those years ago.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Truth is, as much as I love poetry, I didn’t do well in a UT English course which considered the deepest meaning of the craft. I kind of figured if a poet wrote something, they did it because they wanted to tell us something.

The one guy who did that as well as anybody was our old pal Rudyard Kipling. All of us came to know him in high school — or maybe even junior high — from his message of growing up entitled “If.” We learned it, we memorized it, we hung it on our walls for inspiration.

Almost 120 years since he wrote it, lines from the poem are cherry-picked to fit almost every purpose. The rapper Nas included four lines of it as an introduction to the video of his song “Made You Look.” Two of the lines are written on the wall at the tennis players’ entrance to Centre Court at Wimbledon.

And Saturday night in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, perhaps without even realizing it, the Texas Longhorns lived out the words of some of the lines that Kipling had written to his son all those years ago.

For openers, let’s take “If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you….”

When the 2013 team returned from the summer for the start of fall practice drills, Mack Brown had used an overhead projector to map out plans for camp, and for the season. The year would be approached in parts, with separate seasons capsuled within the whole. The first would be the non-conference games. The second would begin with the Kansas State game which marked the beginning of the second quarter of the season, as well as the start of Big 12 play.

But as the week of the K-State game progressed, the team was reminded of a comment by a Wildcat player who had said that Texas quit near the end of last year’s game in Manhattan (which to his credit, he later apologized for in a phone call to Brown). Of the seven writers and editors who pick the games in the local newspaper, three favored Kansas State. Through it all, the team pulled closer together. The leaders led, and the assistant coaches drove them (and themselves) hard all week.

They heard repeatedly about the schedule-skewed “five game losing streak” to Kansas State, dating back to 2003 (even though the Wildcats never faced arguably the Horns’ best four teams of the decade -2004, 2005, 2008 and 2009).

When the rains in Austin on Friday gave way to a nice fall evening on Saturday, with a national television audience and a crowd of upwards of 95,000 watching, the team, whose dreams of going undefeated this season had given way to their second pre-season goal of winning the Big 12, embarked on their next excursion.

The week that has followed has been a time to prepare for the next step. The truth is, if you start out planning to win all the games, it is not unrealistic at all to believe that you can win the rest of them.

Mack Brown‘s message has been based on controlling that which you can control. In other words, focus only on the next game.

“What’s the most important game for us?” he has asked. The logical answer is simply the next — “Iowa State.”

Texas made it through the adversity it faced in the Kansas State game by holding to its theme. Despite injuries, tough officiating and a good, solid opponent, they prevailed because they stuck together.

In the poem, Kipling handles that in the next to last verse with, “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew to serve your turn long after they are gone, and so hold on when there is nothing in you, except the will which says to them: ‘hold on!'”

In the last two meetings against Kansas State, that was the one thing the Horns failed to do. They had chances to win in the fourth quarter in both games, but couldn’t make it happen. This time, they did.

And that is where they hooked into Kipling’s final message to his son: “If you can fill the unforgiving minute, with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run….”

As they approached an open weekend before returning to action next Thursday at Iowa State, the week of practice was a time to work on new things and allow the injured time to heal. As homework, the team will watch games this weekend which will involve all three of their next opponents – Iowa State, Oklahoma and TCU. Each player has been given the assignment to watch the game and bring to their position meetings five things which they saw that might help them win, focusing particularly on Iowa State – which defeated Tulsa on Thursday night.

Rudyard Kipling wrote a long time ago, and he left us both thought and inspiration. And what you find is, that can apply to sports, or it can apply to life.

And for a football team which may be just beginning to claim its identity, it is a message worth remembering.

09.20.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: About the ribbons

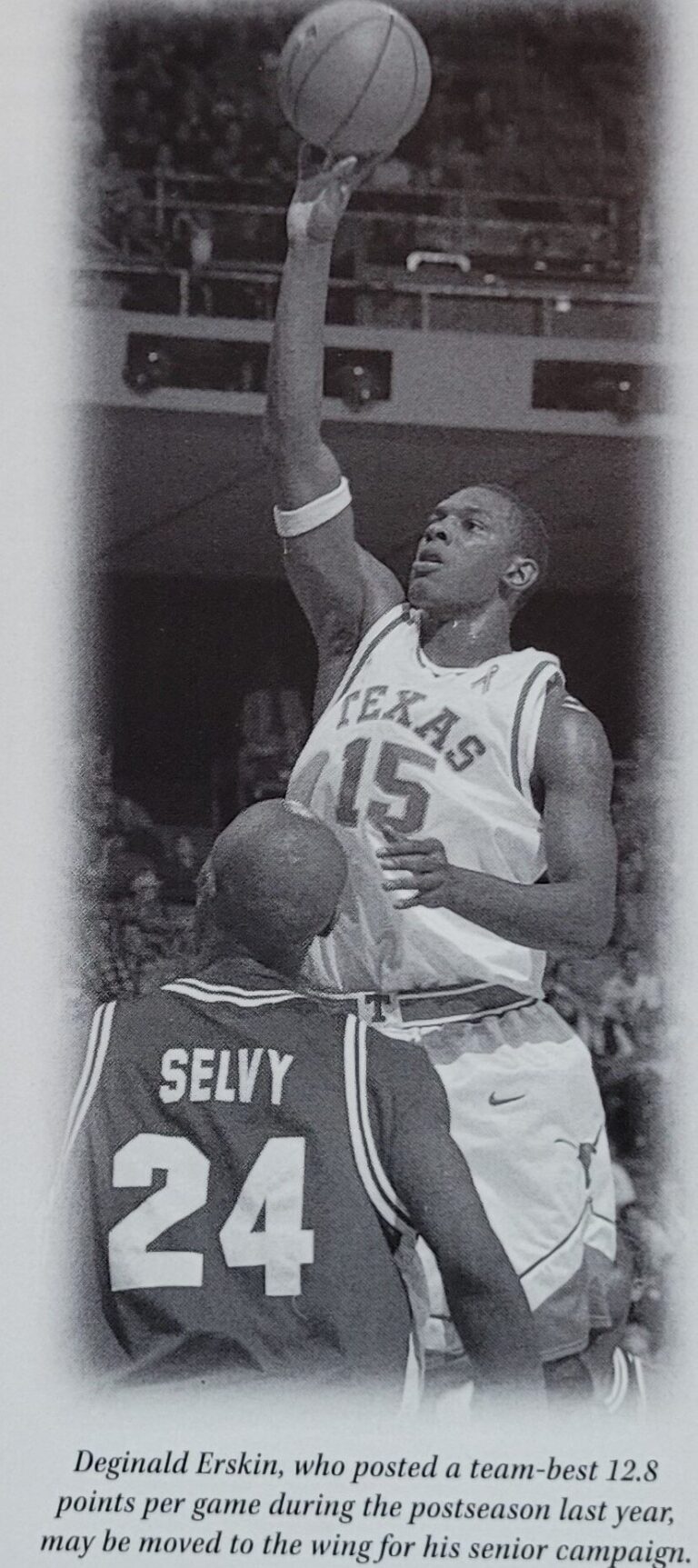

On Saturday, this 2013 Texas Longhorns team will use ribbon decals on their helmets to signify a dedication to a loved one who has battled cancer.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In the days when Hollywood had larger-than-life heroes, it would take a big one to make a simple thing such as a ribbon famous.

Enter John Wayne, who rode as a cavalry officer in the old West, in a movie titled “She Wore A Yellow Ribbon,” and he, the song and the ribbon entered the world of immortality.

When the Texas Longhorn team is asked about things which have touched their lives, two entities immediately out rank others. One is the military, because so many have served, or had great friends and relatives who have served, in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The other is the disease known as cancer.

That is why Saturday, this 2013 Texas Longhorns team will use ribbon decals on their helmets to signify a dedication to a loved one who has battled that disease. We often refrain from using the word “battle” in sports jargon, but there is absolutely no question that when one is fighting cancer, it is a war (albeit of a different kind) for survival.

Several years ago, one of the Longhorns suggested that the team follow the NFL’s lead in recognizing these brave victims who have been stricken — some without any sign or indication of reason — with the life-changing disease.

It is, for all of us, a reminder that while sport is important, it is not a war and it is certainly not a hospital room where the human spirit and modern medicine join forces against a grim reaper with a sickle which cuts through the heart and soul of human kind.

The “Dedication Game” has always been important in Mack Brown‘s program. It has always focused on a theme of playing for somebody else. Each year, team members pick a person who is, or was, close to them and they dedicate their play that day to them.

In the cases of a person who is still living, the players send a note or take time for a phone call before the game to let them know they are playing that day for them. If it is for a person who has passed on, they remember them in various ways.

As the Longhorns embark on their Big 12 Conference season against Kansas State, it seems a perfect time to pause to think about others.

When Case McCoy decided to spend his summer building houses and installing precious water systems in Peru, he told his Dad that he was doing it because, “All my life has been about football and me. I want to do this for someone else.”

The team theme radiates the message that this team will fight for each other. In this symbolic effort on Saturday night, they will be dedicating their collective efforts to fight for somebody else.

As far as the game is concerned, the stars could not have aligned more perfectly for a new beginning. Since entering the Big 12 Conference, Kansas State has been a stumbling block for the Longhorns. In the original alignment where the two schools participated in different divisions and played each other every three and four years, the Wildcats and the Longhorns met in the seasons of 1998 and 1999, then again in 2002 and 2003, and finally in 2006 and 2007. In the ‘Horns’ highest profile seasons of 2004 and 2005 and 2008 and 2009, the teams did not play.

Now, of course, the Big 12 is particularly competitive because with ten teams, everybody plays everybody else every year. And if you are in the business of clearing a path to something (as the Longhorns believe they can be concerning a goal of a Big 12 championship), the first thing you have to do is chop into the brush right in front of you.

Once called by Sports Illustrated “the worst football program in America”, Kansas State has long since put that to rest under the superb guidance of Bill Snyder. The veteran coach has brought the Wildcat program to the top of the Big 12 and has earned national respect. He’s perhaps Mack Brown‘s best friend in the coaching profession, and the two share a dedication to family and football that is evident when you get like minds together.

Saturday’s game will be a showcase, with a national ABC audience watching and listening to Brent Musburger and Kirk Herbstreit.

In the last two meetings, Texas has gone into the fourth quarter with a chance to win against the Wildcats, but in the end the ‘Horns failed to close the deal.

So as they dedicate this game to a cause bigger than college football, you can add the word “fight” with appropriate respect when it comes to the battle against cancer. The ribbons will remind them of that.

You can assume this team will play for each other, so that football, family and faith are paramount in their thoughts. And since the primary goal is to win, they will need to add one more word to their vocabulary.

They need to “finish.”