Steve McMichael

There are six Texas Longhorns who have been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame:

-

Earl Campbell

-

Bobby Dillon

-

Tom Landry

-

Bobby Layne

-

Steve McMichael

-

Tex Schramm

UT’s McMichael Still Fighting, Now An NFL Immortal

by Larry Carlson for https://texaslsn.org

TLSN’s Larry Carlson teaches sports and news media classes at Texas State University. He is a member of The Football Writers Association of America.

Professor Larry Carlson shares a story about Steve McMichael

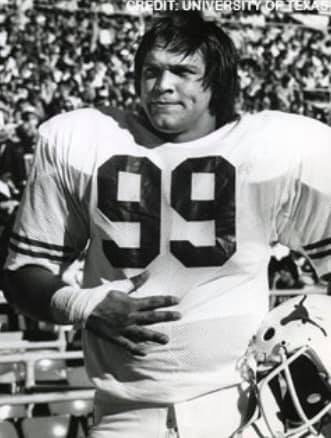

It is a long trek from the rugged old South Texas oil town of Freer to Canton, Ohio, home of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. But Steve McMichael, the 1979 Longhorn All-American defensive tackle, no doubt could’ve crab-crawled it, through prickly pear at the start, to snow-covered ground at his destination.

McMichael, now silenced and physically diminished by the ALS that he was diagnosed with in 2021, but one of the toughest customers to ever buckle a chinstrap, was elected to the Hall of Fame earlier this week.

Bill Acker and Steve McMichael

Various media outlets reported that McMichael was surrounded by his wife, Misty, his sister, Kathy and multiple teammates from the 1985 Chicago Bears’ legendary Super Bowl championship team when the official Hall of Fame announcement came Thursday night.

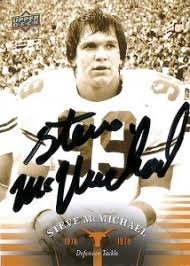

McMichael was a six-sport letterman as a Freer Buckaroo, class of ’76. He played for Darrell Royal that fall, making a name with his fiery, spirited play. In three years as a starter for Coach Fred Akers, he was a figurative Longhorn in the china closet of opposing backfields. Imbued with a happy savagery, he bulldogged runners and terrorized quarterbacks, earning the nickname, “Bam-Bam.”

Big Steve was always a colorful conversationalist and interview when I was with Austin’s KVET Radio. One of my favorite moments with him was when he told our radio listeners the tale of dealing with a rattlesnake at football practice in Freer. “Somebody said there was a rattler at the other end of the field, ” he recalled.

“I went down and beat hell out of him with my helmet. Killed him.”

The New England Patriots drafted McMichael in the third round but let him go before his second season.

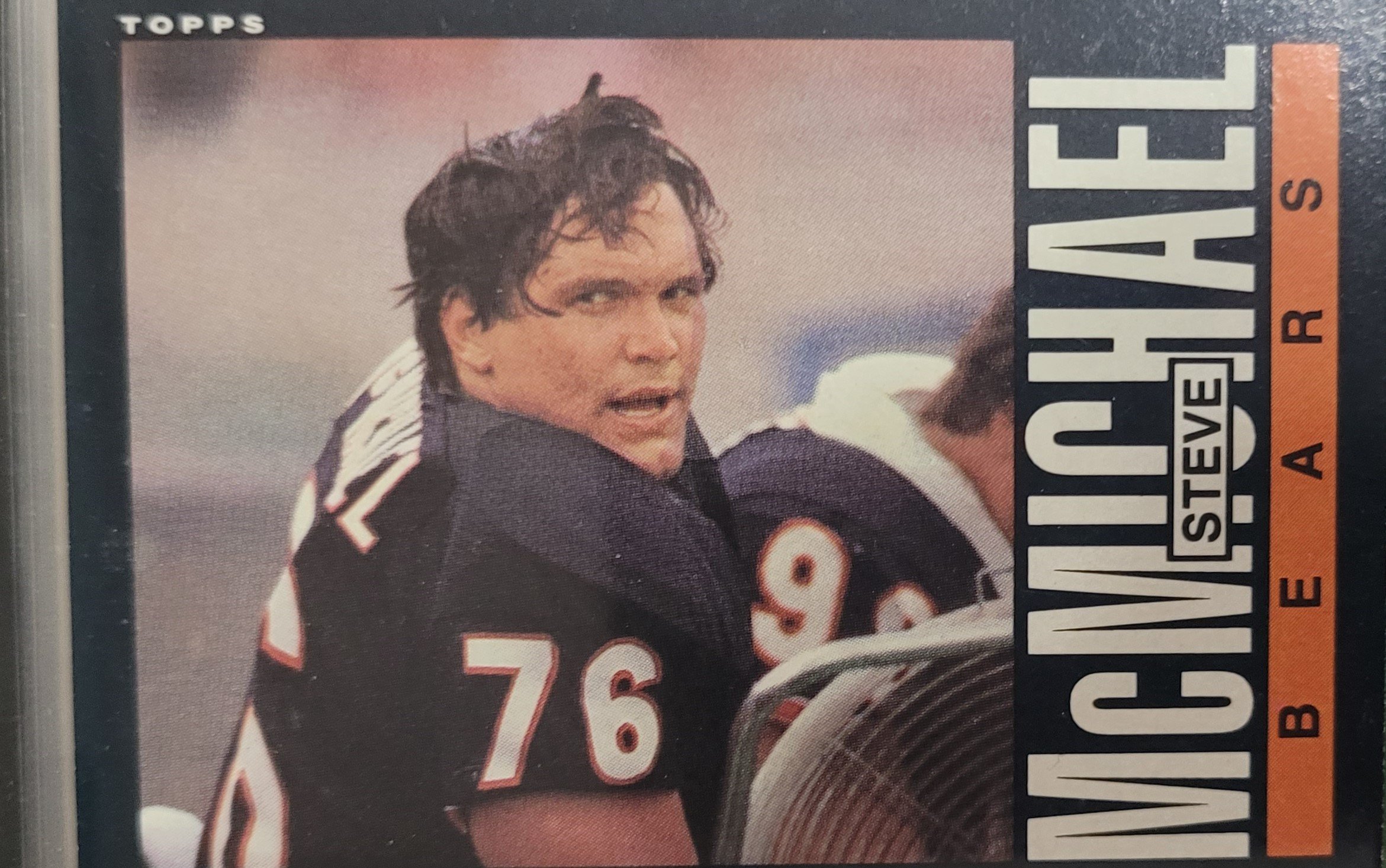

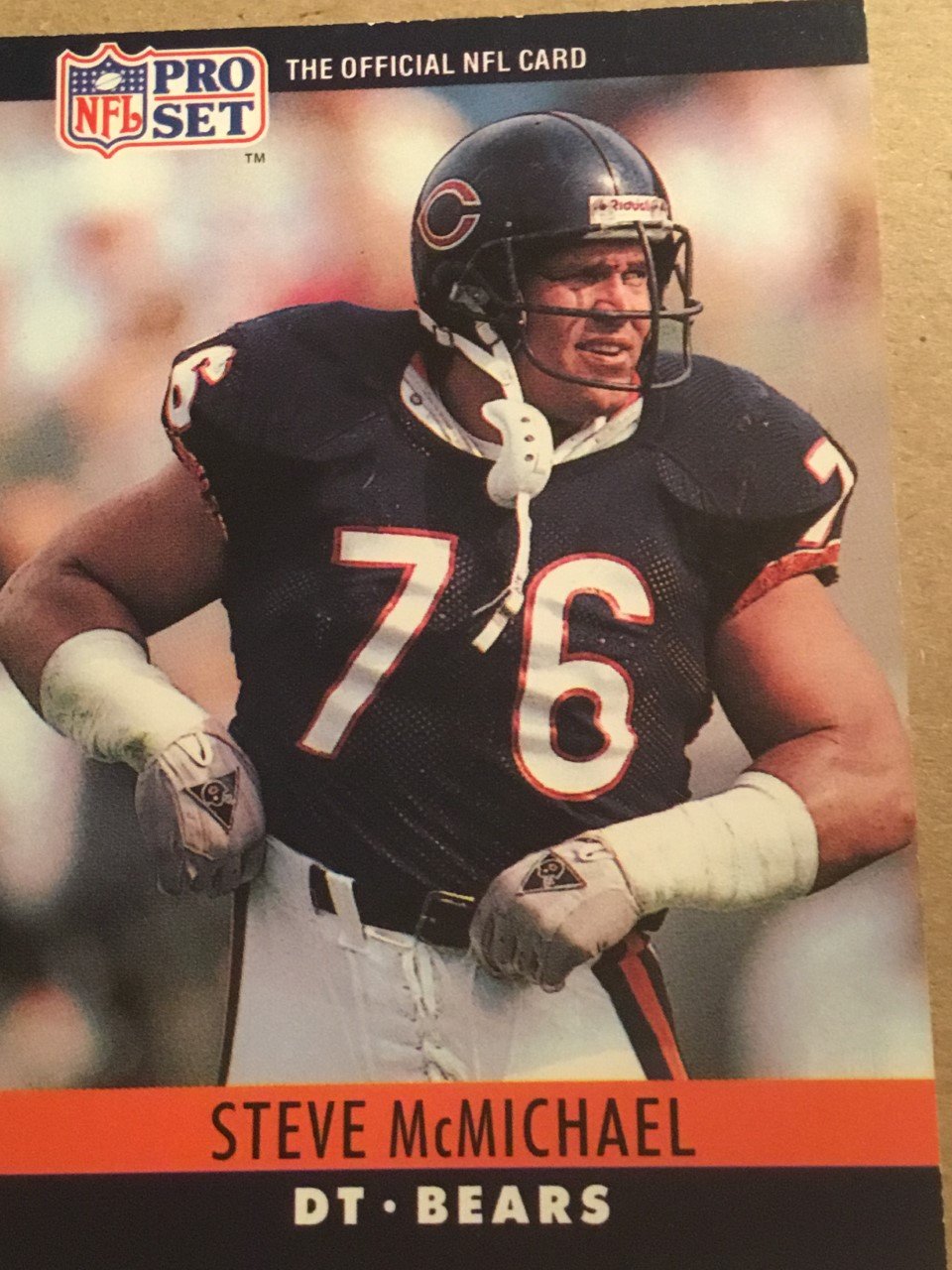

They would regret it. The Bears picked him up and he became an All-Pro and a mainstay, once logging more than 100 straight starts. Teammates tagged him with a new nickname, “Mongo,” based on the movie character played by former NFL star Alex Karras in “Blazing Saddles.” After retirement from football, McMichael quickly emerged as a popular wrestler and later a radio host and head coach of Chicago’s indoor football team.

Over the years, he was inducted into the Texas High School Football Hall of Fame, the UT Athletics Hall of Honor and the College Football Hall of Fame. Now he is the sixth member of the vaunted ’85 Super Bowl champs to earn a spot in immortality at Canton. One of his old Chicago teammates already inducted is linebacker Mike Singletary, the wide-eyed face of the Bears’ crushing defense.

Singletary, perhaps the greatest player ever to come out of Baylor, competed against Steve’s Longhorn teams. Interviewed by ESPN, he saluted his Chicago teammate with a purely Texan tribute.

“When I was a kid, one of my heroes was John Wayne…Steve McMichael was John Wayne,” Singletary said. “He may have been shot in the arm, may have been stabbed in the back, but if you were counting on him to get something done, he was going to get it done.”

Fri 2/16/2024 9:53 AM by Larry Bob Moore

Thanks as always. I coached with a guy who had coached Steve in HS and the Acker brothers in Freer. He told us that Steve had witnessed his father gunned down on the streets of Freer, so to me, he has always been a sympathetic character.

We had tests and measurements together, and I made the highest grade in the class on the first test (I don’t know why the prof announced it out loud). Anyway, when we had our next exam, Steve sat beside me, and when I made it a point to cover my paper with my arm, Steve said, “Move your arm, and of course I did, quickly!

He became my partner for the field testing portion of the class, and he was so competitive that he always shorted me by a few reps or seconds, but I didn’t care. I figured I’d make an A in the class regardless. He didn’t need to underreport my efforts in the football throw. I heaved it out there about 45 yards, and I swear he threw the ball right at 90 yards. It was not a regulation football, but it was still one of the most amazing feats I’ve ever witnessed.

Larry Bob

Click on red font below starting with “Steve McMichael”.

April 30, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

If it is as they say — that there is a thin veil between life and death — then somewhere from a place beyond E. V. McMichael is smiling right now.

It has been a long time since that night in 1976 when young Steve McMichael was returning to Austin after starting his very first game as a Texas Longhorn defensive end against the Texas Tech Red Raiders in Lubbock. A lot would change that late October night. The night before the game, Darrell Royal would confide to some close associates that he likely would retire as the Texas head football coach following the season.

Earl Campbell, the star of the team, would re-injure a hamstring and would miss the next four games in what would turn out to be a 5-5-1 season. For Steve McMichael, a sturdy young freshman from Freer who had been considered for the tight end position, his first start as a Longhorn had ended in a 31-28 loss to the Red Raiders.

But that night — October 30, 1976 — young Steve would learn the difference between the game of football and the reality of life. That night, E. V. McMichael, an oil field superintendent, was shot to death outside his home in South Texas.

In the years that would follow, Steve would stick with the game E. V. had helped teach him. Where it was football that had brought him to The University of Texas, it would be Steve’s drive and dedication that would carry him to the greatest heights of the game.

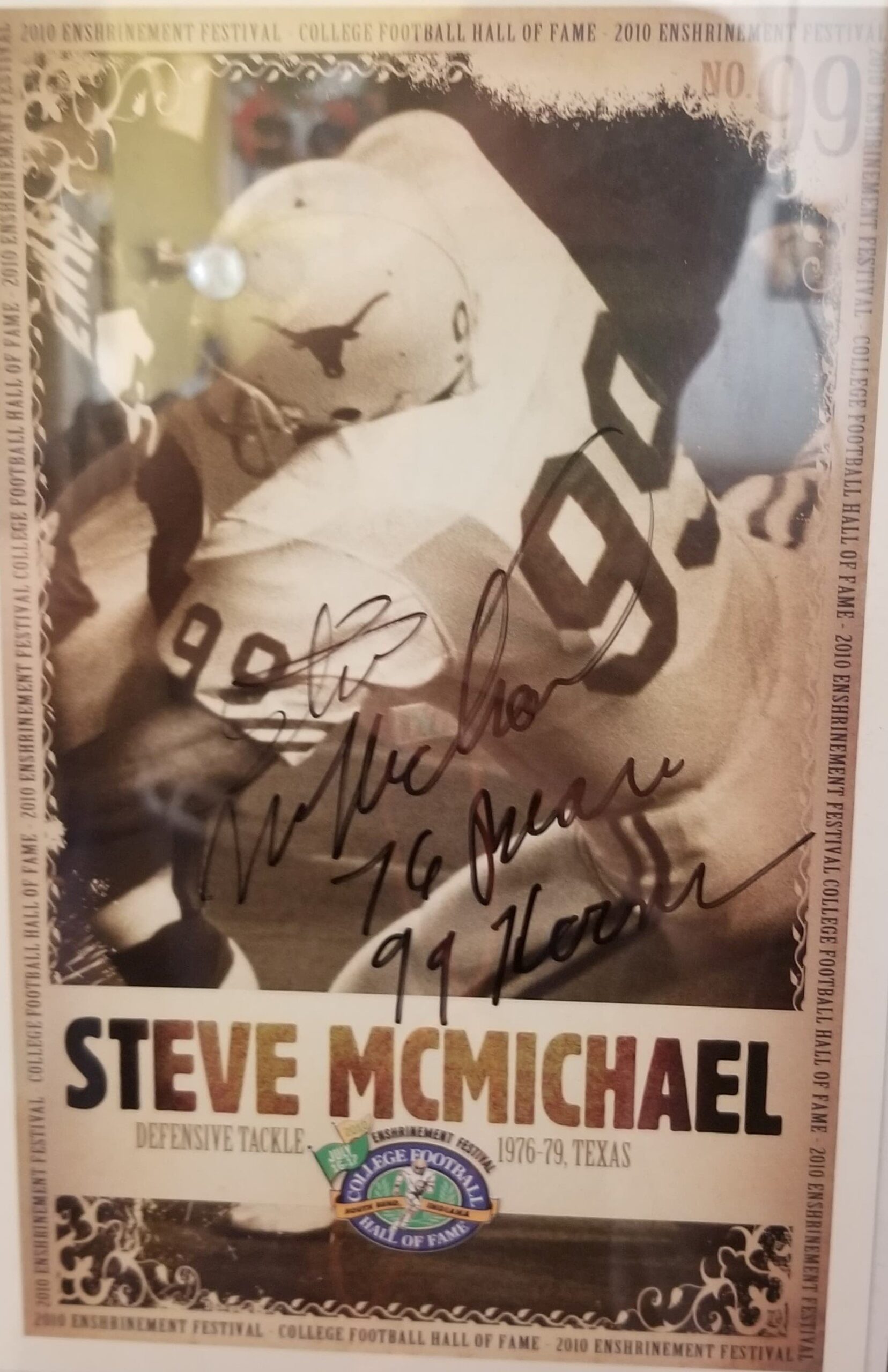

That is why, on Wednesday, when Steve McMichael was announced as the Texas Longhorns’ 15th player and 17th overall inductee (including coaches D. X. Bible and Darrell Royal) into the National Football Foundation’s College Hall of Fame, you have to figure there was a loud cheer somewhere beyond the sky.

“I will never be able to thank The University of Texas enough for what it did for me during that time,” McMichael recalled from his home in Chicago, where he was a star in the NFL for the Bears and is now the head coach of the arena league Chicago Slaughter. “My ‘old man’ put me on the road, but if it hadn’t have been for Texas, I have no idea where I would be right now.”

McMichael joins a class that includes, among others, Tim Brown of Notre Dame, Major Harris of West Virginia, Chris Spielman of Ohio State, Curt Warner of Penn State, Gino Torretta of Miami and Grant Wistrom of Nebraska.

There were those, during his playing days at Texas, who would swear that McMichael was the poster boy for the old cartoon showing a grizzled guy with a menacing look with the take off on the Bible scripture saying, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of death, I will fear no evil…’cause I am the meanest dude in the valley.”

Back at Texas Tech his junior year, when the Red Raiders’ spirit group came to the airport and rolled out a red carpet, McMichael and his fellow tackle Bill Acker took one look at the welcome gesture, then pushed through the red-and-black clad students and walked around the carpet. Texas won the next day, 24-7.

His senior year in 1979, as part of perhaps the best defense in Texas history (it allowed an average of only nine points per game), McMichael personally dominated the 1978 Heisman Trophy winner Billy Sims in the Longhorns’ 16-7 victory over the Sooners. Sims gained only 73 yards on 20 carries, and McMichael registered 13 tackles — nine against the running game.

McMichael totaled 133 tackles during his senior season, and posted 369 tackles, 30 sacks, 40 tackles behind the line, 99 quarterback pressures and 11 caused fumbles during his career as a Longhorn.

In the NFL, McMichael’s name would become famous in Chicago, where he would help lead the Bears to some of their greatest moments, including a Super Bowl win in the 1985-86 season. Drafted and later cut by the New England Patriots in 1980, McMichael rebounded to become a two-time Pro Bowler in Chicago. He played 14 years in the league, retiring in 1994 after a final season with Green Bay. He set a Bears’ record by playing in 191 consecutive games, and during his career he registered 95 sacks and played in 213 NFL games.

He then took a spin as a professional wrestler before retiring in 1999. In 2001, he returned to Chicago where he has hosted the Chicago Bears pre- and postgame shows on the local ESPN radio affiliate.

His Chicago Slaughter Professional Arena team is 7-0 and has clinched the Western Division of the Continental Indoor Football League, doing so with a 78-25 victory over Milwaukee last Saturday.

A member of the Longhorn Hall of Honor, the Texas High School Sports Hall of Fame and the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame, McMichael is involved in numerous charities, most notably the Fisher House Foundation and other organizations that support wounded soldiers and their families.

McMichael becomes the second member of his Longhorn era to be inducted into the NFF Hall of Fame, joining safety Johnnie Johnson, who was enshrined in 2007. Upon his induction during the December festivities in New York, Johnson allowed that he would have made a lot more tackles, had McMichael not made them all before they could get into the secondary.

“I can tell you this,” McMichael said Wednesday. “I will be wearing orange. There is no way to describe how much this means, or how thankful I am to all of the people who helped me at Texas. All I can say is, ‘Hook ’em!'”

It is a long way from Freer, Texas, to the ballroom of the storied Waldorf Astoria in New York City. The years perhaps have dulled the pain of that night so very long ago that changed the life of a young freshman. But when Steve McMichael, his wife and new baby girl celebrate that moment in the grand old hotel, there will be a lot of pride in a lot of places, seen and unseen.

Because, you see, in his playing time at Texas and at Chicago, many people saw the tough exterior of a man carved from the dust of the land and the steel of the spirit. But what drove Steve McMichael was a wry smile that reflected someone who could see the fun side of life, even in the hard times. It was paired with a fierce determination and an unbending drive of competition.

Most of all, it was about matters of the heart — the kind which fought undaunted, perhaps bloody, but always unbowed.

https://www.texaslsn.org/leducs-mean-and-bad-boy…

https://www.texaslsn.org/steve-mcmichael

David Bales is the Former Chairman for Stem Cell Research for the State of Texas.

David is on the left in this photo with Coach Akers

David says “Steve, “Mongo” McMichael used to tell how he was “short-changed in his career. In the 78 Cotton Bowl, all the players were given Seiko watches instead of the Rolexes teams were given in previous years. Shortchanged.”

Then he won the MVP in the Hula Bowl . Previous winners were given a car. The Governor of Hawaii gave him a wooden monkey bowl. Shortchanged again.

But the biggest shortchange is Steve is not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He’s in the Texas High School, the Longhorn, and the College Hall of Fame.

Yesterday Bryant Young a DT for the 49ers that played 14 years was inducted into the HOF. Nothing against Young, but Steve played longer (16 years), and has more sacks 105 to Young’s 89. More games 213to 208, more tackles 847 to 618. Whet could the voters be thinking?

Jersey signed by Steve McMichael compliments of Ben Papp

When Richard Dent was inducted and then Jimbo Covert, they both said in their induction speech, “ The Pro Football Hall of Fame will not be completed until Steve gets in”. I couldn’t agree more. Steve always said he wouldn’t get in because he didn’t kiss sportswriters’ asses.

We all know Steve is suffering from ALS and these sportswriters should have done the right thing and vote Steve into the hall. Stop SHORTCHANGING one of the greatest football players in history!!

“He was cut from a different cloth,” recalled Tommy Roberts, who was Freer head coach when McMichael was a three-year starter from 1973 through 1975. “He was a terror in the making. You could see it coming. He was just young. They hit as a pup, they’ll hit as a dog.

Steve McMichael’s Hula Bowl MVP gift presented by GQ Model David Bales

“It was fun to be a part of bringing him along. Steve had a mean streak on the field. He wanted to get to the ball and hurt whoever had it in their hands. He had no pain. He would just throw that aside. He was just brutal and he took no mercy on anybody on the football field.”

The infamous Hawaiian monkey bowl Steve won as the MVP of the Hula Bowl All Star game. He told me you could buy one for $20 on the streets of Hawaii- shortchanged again!

He wanted me to thank all of you for supporting him and believing he should be in the Hall of Fame.

We had some good laughs and he continues to fight. His the ones you care about and tell them you love them ;))

at Texas his teammates called him Bam Bam; at Chicago, his teammates called him Mongo

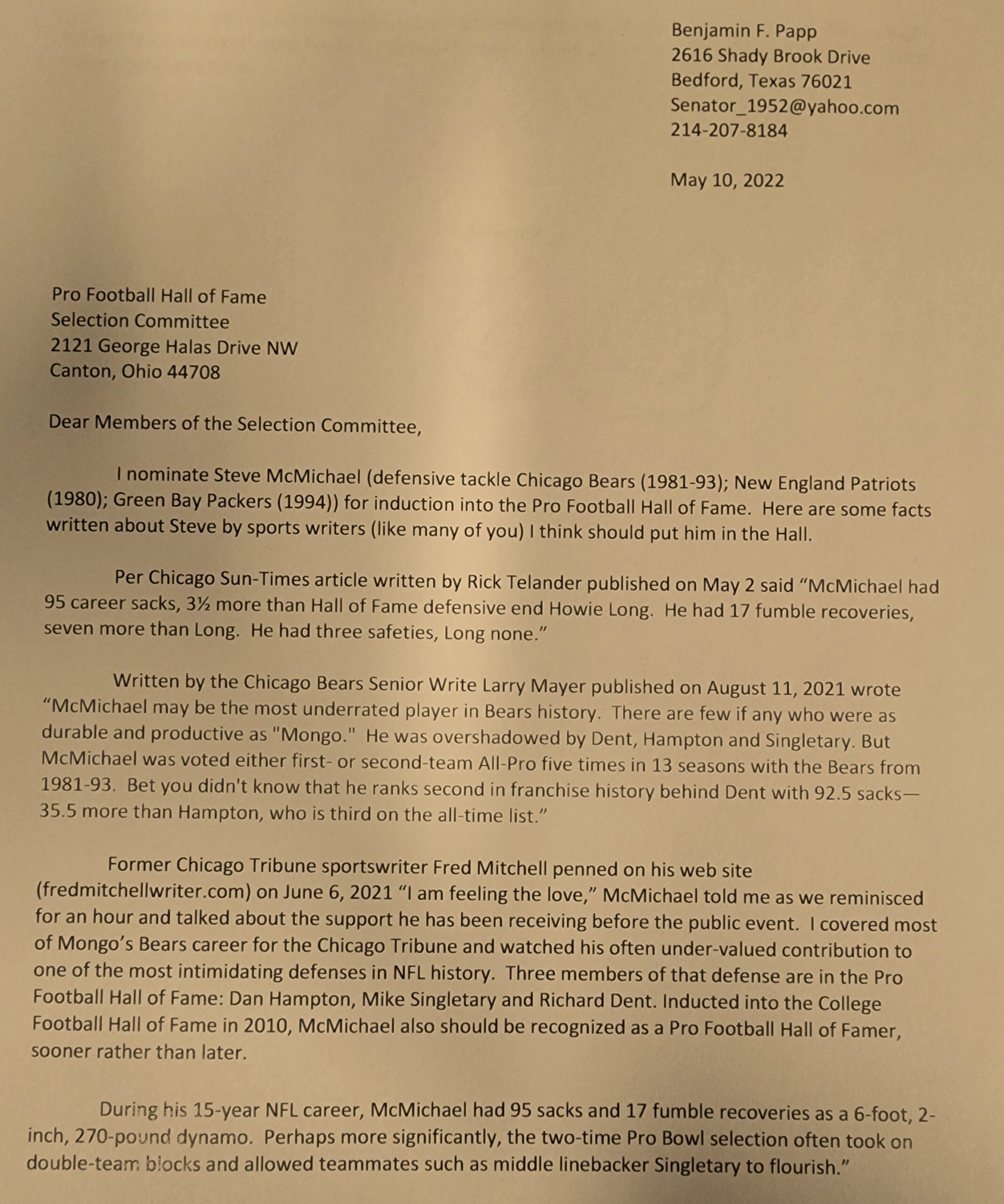

Benjamin Papp’s letter requesting Steve McMichael addition to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Battling ALS is not a fight Chicago Bears Legend ever thought he would have to wage. But it’s one he’s taking on with the same determination and tenacity as he did for so many years on the football field. Click on the image for the rest of Steves’s story.

May 2022 – Click on the link in blue font below.

Steve McMichael a Hall of Famer? Our man says yes – Chicago Sun-Times (suntimes.com)

Chicago Bears Super Bowl XX Champion and fans favorite, Steve “Mongo” McMichael, has been diagnosed with ALS (or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis is also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease). Steve was diagnosed in January with a 36-month onset. Steve has been suffering in silence for too long. He is paralyzed from the shoulders down so his wife of 20 years, Misty, feeds him and supports him with all hygiene needs. Steve’s legs are weakening and he uses a customized wheelchair provided by the Chicago Bears.

APRIL 29, 2021by Betsy Shepherd, Organizer

Hello Team Mongo! We were with Steve, Misty, and Macy today as he had his first doctor’s appointment with the top ALS doc at Northwestern. What a wonderful group of medical professionals we met with. I have to be honest with you though, this is a very tough road. Just in the last week, Steve has declined. He’s in a lot of pain, and his hands and feet are very swollen. Thankfully the doctors are prescribing meds that will help him and equipment that will help him sleep better. We are in good hands. Beyond that, they have prescribed 24/7 care for Steve. Misty can’t do this on her own any longer. God bless her. These two were made for each other, and the love they share is evident. We ask for your prayers for Steve, Misty, and Macy as we all navigate this next phase of Steve’s illness. Steve and Misty asked us to thank you all for the love and support. You’ve taken a huge burden off their shoulders. We are almost to the goal. Please continue to share this page and go to www.ObviousShirts.com for TEAM MONGO shirts and www.TeamMongo76.com for bracelets. Everything helps, and Steve needs us as much as we’ve needed him as Bears fans! God bless you all. ⬇️

#TeamMongo

The South Texas Kid

by Larry Carlson

It was the Saturday afternoon post-game show in Austin and Steve McMichael was telling me, and a live radio audience, another wild, humorous story about Longhorn football and life back in his rough and tumble South Texas oil patch town of Freer. One of his Buckaroo teammates had spotted a large rattlesnake at one end of the dusty practice field during a brief water break. McMichael said he had jogged downfield to verify the report.

Lured in again by a natural storyteller, I asked him what happened next.

“Yeah, it was a rattler, alright. So I took off my helmet and beat the hell out of him with it,” McMichael said, matter-of-factly. “Killed him.”

McMichael, certainly one of the most colorful characters to ever wear the burnt orange, was nicknamed “Bam-Bam” by UT teammates, to fit his playful caveman, wrecking ball persona, long before he was dubbed “Mongo” while starring for the swashbuckling Super Bowl champion Chicago Bears of ’85.

From 1976-79, the rugged Longhorn defensive tackle took on blockers, ballcarriers, and quarterbacks the way he handled brush country snakes. Seek. Then maul. He took no prisoners.

I have long recalled the glee McMichael exploded with once when he hit the sidelines after a jarring sack of an opposing Southwest Conference QB. “Answer the phone, bitch,” he yelled to everyone, a huge smile on his face as the quarterback trudged shakily to his bench, head no doubt ringing from the clean but brutal body slam.

Steve McMichael has long been larger than life. Pecos Bill in shoulder pads, whipping up havoc on hapless offenses and lassoing ball carriers with a happy savagery. Six-sport letterman at Freer. All-American at Texas. Pro-Bowler in Chicago. Then a championship wrestler and media personality.

So it is extra hard for fans, followers, and former teammates to accept the recent news that McMichael has been stricken by ALS, put in a specialized wheelchair by the nefarious forces of a deadly disease.

McMichael, characteristically, was still able to muster wisecracks while discussing his ALS diagnosis with the Chicago Tribune. “I thought I was ready for anything,” Steve said. “But this will sneak up on you like a cheap-shotting Green Bay Packer.”

Reading of McMichael’s situation, I flashed back to a time back in the disco daze of the late 1970s when Austin nightclubs featured large, flashing dance floors that, along with cheap beer and buck-fifty drinks that were slung instead of “crafted”, attracted many UT students, especially on Thursday nights. Doors were even open to young sportscasters and other starving media types.

From the bar, I spotted McMichael out on the floor, dancing with yet another pretty coed while the bass thumped to Earth, Wind & Fire, and Donna Summer. What made me smile and shake my head was not that McMichael looked out of place, like some large, lumbering Travolta wannabe. I had seen him dance there before, and he wasn’t doing the Cotton-eyed Joe. He was rather nimble, I recall and seemed to be having a blast, his trademark smirk on broad display.

My surprise came because, according to the coaching staff, Big Steve was nursing a very sore knee and was “iffy” for Saturday.

Ol’ number 99 knew better. Come Saturday at the stadium, he kicked butt. He always did. It’s what he does.

Godspeed, Steve.

ARTICLE BY LARRY CARLSON

Below is an article that Bill Little wrote in 2009 for Texassports.com that shares Steve McMichael’s induction into the National Football Foundation’s College Hall of Fame.

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: A PLACE IN THE HALL — STEVE MCMICHAEL

APRIL 30, 2009

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

If it is as they say — that there is a thin veil between life and death — then somewhere from a place beyond E. V. McMichael is smiling right now.

It has been a long time since that night in 1976 when young Steve McMichael was returning to Austin after starting his very first game as a Texas Longhorn defensive end against the Texas Tech Red Raiders in Lubbock. A lot would change that late October night. The night before the game, Darrell Royal would confide to some close associates that he likely would retire as the Texas head football coach following the season.

STEVE MCMICHAEL WAS INDUCTED IN 2009

Earl Campbell, the star of the team, would re-injure a hamstring and would miss the next four games in what would turn out to be a 5-5-1 season. For Steve McMichael, a sturdy young freshman from Freer who had been considered for the tight end position, his first start as a Longhorn had ended in a 31-28 loss to the Red Raiders.

But that night — October 30, 1976 — young Steve would learn the difference between the game of football and the reality of life. That night, E. V. McMichael, an oil field superintendent, was shot to death outside his home in South Texas.

In the years that would follow, Steve would stick with the game E. V. had helped teach him. Where it was football that had brought him to The University of Texas, it would be Steve’s drive and dedication that would carry him to the greatest heights of the game.

That is why, on Wednesday, when Steve McMichael was announced as the Texas Longhorns’ 15th player and 17th overall inductee (including coaches D. X. Bible and Darrell Royal) into the National Football Foundation’s College Hall of Fame, you have to figure there was a loud cheer somewhere beyond the sky.

“I will never be able to thank The University of Texas enough for what it did for me during that time,” McMichael recalled from his home in Chicago, where he was a star in the NFL for the Bears and is now the head coach of the arena league Chicago Slaughter. “My ‘old man’ put me on the road, but if it hadn’t been for Texas, I have no idea where I would be right now.”

McMichael joins a class that includes, among others, Tim Brown of Notre Dame, Major Harris of West Virginia, Chris Spielman of Ohio State, Curt Warner of Penn State, Gino Torretta of Miami, and Grant Wistrom of Nebraska.

There were those, during his playing days at Texas, who would swear that McMichael was the poster boy for the old cartoon showing a grizzled guy with a menacing look with the take-off on the Bible scripture saying, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of death, I will fear no evil…’cause I am the meanest dude in the valley.”

Back at Texas Tech his junior year, when the Red Raiders’ spirit group came to the airport and rolled out a red carpet, McMichael and his fellow tackle Bill Acker took one look at the welcome gesture, then pushed through the red-and-black clad students and walked around the carpet. Texas won the next day, 24-7.

His senior year in 1979, as part of perhaps the best defense in Texas history (it allowed an average of only nine points per game), McMichael personally dominated the 1978 Heisman Trophy winner Billy Sims in the Longhorns’ 16-7 victory over the Sooners. Sims gained only 73 yards on 20 carries, and McMichael registered 13 tackles — nine against the running game.

McMichael totaled 133 tackles during his senior season and posted 369 tackles, 30 sacks, 40 tackles behind the line, 99 quarterback pressures, and 11 caused fumbles during his career as a Longhorn.

In the NFL, McMichael’s name would become famous in Chicago, where he would help lead the Bears to some of their greatest moments, including a Super Bowl win in the 1985-86 season. Drafted and later cut by the New England Patriots in 1980, McMichael rebounded to become a two-time Pro Bowler in Chicago. He played 14 years in the league, retiring in 1994 after a final season with Green Bay. He set a Bears’ record by playing in 191 consecutive games, and during his career, he registered 95 sacks and played in 213 NFL games.

He then took a spin as a professional wrestler before retiring in 1999. In 2001, he returned to Chicago where he hosted the Chicago Bears pre-and postgame shows on the local ESPN radio affiliate.

His Chicago Slaughter Professional Arena team is 7-0 and has clinched the Western Division of the Continental Indoor Football League, doing so with a 78-25 victory over Milwaukee last Saturday.

A member of the Longhorn Hall of Honor, the Texas High School Sports Hall of Fame, and the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame, McMichael is involved in numerous charities, most notably the Fisher House Foundation and other organizations that support wounded soldiers and their families.

McMichael becomes the second member of his Longhorn era to be inducted into the NFF Hall of Fame, joining safety Johnnie Johnson, who was enshrined in 2007. Upon his induction during the December festivities in New York, Johnson allowed that he would have made a lot more tackles, had McMichael not made them all before they could get into the secondary.

“I can tell you this,” McMichael said Wednesday. “I will be wearing orange. There is no way to describe how much this means, or how thankful I am to all of the people who helped me at Texas. All I can say is, ‘Hook ’em!'”

It is a long way from Freer, Texas, to the ballroom of the storied Waldorf Astoria in New York City. The years perhaps have dulled the pain of that night so very long ago that changed the life of a young freshman. But when Steve McMichael, his wife, and his new baby girl celebrate that moment in the grand old hotel, there will be a lot of pride in a lot of places, seen and unseen.

Because, you see, in his playing time at Texas and at Chicago, many people saw the tough exterior of a man carved from the dust of the land and the steel of the spirit. But what drove Steve McMichael was a wry smile that reflected someone who could see the fun side of life, even in the hard times. It was paired with a fierce determination and an unbending drive for competition.

Most of all, it was about matters of the heart — the kind which fought undaunted, perhaps bloody, but always unbowed.

‘Ooooh, the skulduggery!’: Inside the world of Steve McMichael, still one of the most colorful and beloved characters from the 1985 Bears

By Dan Wiederer

Chicago Tribune

Aug 26, 2019 at 7:00 am

Steve McMichael reaches across the table for a handful of Mongo nachos, plopping a mound of corn chips, beef, queso and olives onto his plate and taking a moment to catch his breath. If the wooden chairs at McMichael’s Romeoville sports bar were equipped with seat belts, now might be a good time to buckle in.

This intermission won’t last long and for the past 20 minutes, McMichael’s sermon has been fast-paced and all over the place, the ruminations of a Bears legend explaining the meaning of life. Or something like that.

Even for an audience of one, McMichael understands how to be captivating, mixing detailed old stories with off-color jokes and philosophical musings and driving it all home with his emphatic tone and distinct Texas drawl.

One minute, he is passionately pushing his next crusade — to require shoulder pads at every level of football to be fitted with a neck collar to reduce the whiplash effect that accompanies concussions. The next minute, he is glancing over his head at a framed jersey and photo from the 1987 Pro Bowl and lamenting how his hiked-up uniform pants always used to, um, make him quite uncomfortable below the belt.

McMichael is dressed like the Terminator. Black sunglasses on his head, black leather coat, black crew-neck T-shirt, black pants, black boots. But suddenly the former Bears defensive lineman has found himself in a deeply reflective moment, appreciative of all the spoils his football career has provided.

He wants the people of Chicago to understand how deeply blessed he has felt for nearly 40 years to bask in their adulation.

[ Ranking the 100 best Bears players ever: No. 18, Steve McMichael » ]

Sure, McMichael spent 13 seasons with the Bears fueled by his intense inner drive. But, he says, he also felt an obligation to give all those bare-chested, barking maniacs in the stands a little more. That’s part of the reason he practiced with such intensity and played with reckless abandon. That’s part of the reason he always felt an extra urge to put on a show.

“A Monster of the Midway is an entertainer,” he says.

McMichael is now thinking about all those times he stopped to sign autographs, to crack a few jokes, to spend time with the adoring masses. His voice gets quieter.

Steve McMichael enjoys a respite on the Bears bench during a 1991 game. (Bob Fila / Chicago Tribune)

“You know what was always the worst thing I ever had to do?” McMichael says. “I would stand out there after training camp and there’d be thousands of people. They bring their kids and they’ve got them shoved up there (against the ropes) to get autographs. And I’d stay as long as I could. But now I’m going to be late for meetings. Or I have to go get dinner and get cleaned up. And I’d have to leave some of those little kids without an autograph.”

He pauses and swallows.

“That was the worst I’ve ever felt about myself. Honestly.”

He shakes his head and exhales. “It was the worst I ever felt about myself.”

And this, he laments in vivid detail, from a guy who was once the victim of an unfortunate bait-and-switch with a stripper in a seedy pocket of Thailand.

“And that,” McMichael announces, “is why I’ll never go back to Bangkok! Mongo has been ignorant!”

His eyes are the size of golf balls. He is grinning ear to ear. . Indeed, things are not always as they appear.

This is the quintessential McMichael experience. Some more-than-meets-the-eye introspection punctuated with a ribald quip. This, it seems clear, is why a full 34 years after the Bears won their only Super Bowl, McMichael remains one of the most colorful and compelling characters from Chicago’s most iconic team.

* * *

‘It’s 1984 and we’re walking out to play the Hogs and John Riggins in the playoffs. I heard a dog barking nonstop in the tunnel. I thought to myself, “What do they have some kind of mean (expletive) Frisbee dog coming out here to perform?” But then I looked around and I realized it was me.’

* * *

Any offensive player who played for the Bears in the ’80s can hear the echoes.

“Come out of that (expletive) huddle!”

This was McMichael’s method of challenging his teammates on the other side of the ball, of provoking them, of letting them know that, even in practice, they needed to bring everything they had or risk being embarrassed.

“The only way you can get a tired offensive lineman to bust his ass is to piss him off,” McMichael says.

This, McMichael believes, is how you set a tone, how you create a mindset.

It’s the same reason he took time before almost every game to wander to the 50-yard line. Just to stand. Just to let his blood boil. Just to let his eyes grow wide and his competitive juices flow.

“I was building up my resolve,” he explains. “You know what’s in the heart of a champion? Fear of failure. It’s the fear of his personal failure that drives him more than anything else.”

Still, McMichael also loved daring opponents to notice his maniacal look and to decide how to process it.

Long after his retirement, he was approached by former Vikings quarterback Wade Wilson, who immediately brought up that customary midfield staredown.

Says McMichael: “I asked him what he thought about it. He said, ‘We all thought, “Look at that crazy (expletive).” ’ I told him I’m glad it had its desired effect.”

The Buccaneers’ James Wilder is stopped by the Bears’ Steve McMichael (76) and Wilber Marshall during a game in October 1987. (Ed Wagner Jr. / Chicago Tribune)

In the rich history of the Chicago Bears, a franchise that prides itself on grit, toughness and loyalty, no offensive or defensive player has ever played more games than McMichael’s 191.

To be clear, those were all in a row. From Week 7 of 1981 until Week 18 of 1993. His entire Bears career. Through eight knee surgeries. Never a game missed.

“That’s resolve,” McMichael says. “You find out who you are, my friend. And when that adrenaline is flowing, baby, that’s the painkiller that can’t be matched anywhere in the world. That’s the juice you’re going to miss when you can’t do it anymore.”

That one number — 191 — speaks volumes.

“It’s incomprehensible,” says longtime teammate Dan Hampton, who played for 12 seasons and 157 games and was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Hampton admits he wanted to despise McMichael. And all these years later he knows exactly why he never could. Hampton was born in Oklahoma and played at Arkansas, a Southwest Conference rival of McMichael’s Texas Longhorns. Hampton can still feel the sting of losses to Texas his junior and senior years.

“I grew up hating Texas,” Hampton says. “And nobody typified Texas more than Steve McMichael. He was loud. He was brash. It was that ‘Everything is bigger and better in Texas’ kind of thing.”

So when the Patriots threw McMichael away in 1980 and the Bears later grabbed him off the curb as a reclamation project, Hampton wasn’t expecting to be gaining a dependable teammate much less a lifelong friend.

But behind the boisterous and barbaric exterior, Hampton quickly realized how damn hard McMichael worked, how much he pushed to get the most out of himself and others around him. During the rise of the vaunted Bears defense in the early- to mid-1980s, no player took the pursuit of excellence more seriously.

Hampton loved that dedication, loved watching the defense feed off McMichael’s rollicking energy and loved seeing the Bears offense fight to match the tenacity.

Says former Bears coach Mike Ditka: “Steve gave an air about not giving a damn. And he gave an air about not being a really smart guy. But he is. He has always been a smart guy. And he did give a damn.”

Hampton recalls the Saturday nights when he and McMichael would get their knees drained in order to play. He fondly remembers the plane rides back from road games with the two of them dulling their pain with a couple of cigars and a liter of Crown Royal.

On game days, when either of them would make a big play, there was never a showy sack dance. McMichael and Hampton would just look each other in the eye, smile and recite their shared catchphrase. “Now you’re talking pro football!”

“And we’d just laugh,” Hampton says. “Like, hey, this is who we are. This is what we do.”

* * *

‘If you think I’m something special, I’m happy to agree with you.’

* * *

It’s 9:26 on a June Sunday morning and the line of Bears fans snaking down River Road in Rosemont has begun pouring into the Donald E. Stephens Convention Center for Day 3 of the Bears100 Celebration.

Ten minutes earlier, a “Chasing Great” panel began in Hall A featuring current Pro Bowl Bears Kyle Fuller and Charles Leno discussing the 2019 team’s Super Bowl pursuit. But at this moment, the gathering in the autographs line is far larger.

McMichael is behind a row of curtains preparing for his hour-long signing session and has not yet seen that the line for his table is, at this point, at least three times as long as the one funneling toward Matt Nagy and Ryan Pace.

As usual, McMichael is a bit hyper, raring to go.

“Can I get started a few minutes early?” he asks a convention worker.

“You’re going to want to,” the man answers. “Your line is the longest we’ve seen so far. It’s already practically out the front door.”

McMichael nods, smiles widely and extends both his arms.

“And whyyyyy wouldn’t it be?” he booms. “The ancient Greeks called me a demigod!”

On the surface, it may sound haughty. But it’s not that. At least not entirely. For nearly four decades now, McMichael has been amazed that the affection Bears fans show him hasn’t receded. He’s constantly energized by their energy.

That’s why during every interaction like this, at every public event and in every random encounter, McMichael strives to give his followers a true sampling of the Mongo experience. A moment they’ll feel good about, a one-liner they’ll tell their friends and family about.

“I know how most divas treat people. Like (expletive) on their shoe,” McMichael says. “People come up to me and say, ‘I don’t mean to bother you …’ Bother me? If you think I’m something special, I’m happy to agree with you.”

Adds Hampton: “He always understood that without the fans we were just a bunch of Sasquatches out there ramming into each other.”

Lisa Nowak of Skokie learns about football by helping Bear defensive tackle Steve McMichael suit up at a clinic on Oct. 23, 1984. (Quentin C. Dodt / Chicago Tribune)

More often than not, McMichael can’t even sign his full name without stopping to tell a joke or an old story. A middle-aged man comes to the table with a pencil drawing of the Bears defensive lineman from the ’80s. McMichael grabs it from him and before scribbling his signature takes a long look at the artist’s rendering.

“God, I used to be pretty!” he says. “Now look at me!”

An attractive woman — brunette, probably late 30s — comes to the table with a smile. She seems smitten but shy.

“You know everything in your mind right now wondering what this would be like?” McMichael cracks. “It’s all true!”

For an hour, McMichael signs everything that’s brought to him. Drawings, miniature helmets, photographs, old posters.

Against convention guidelines, he grants every request for a quick photo and signs multiple items for those bold enough to ignore the one-signature-per-person restriction. A volunteer recognizes the amount of time McMichael is spending with each fan may prevent him from getting through even half the line of people waiting.

“Guys!” he orders, “Have whatever you want Mr. McMichael to sign ready when you get up here. We need to keep this moving! Please be prepared!”

McMichael laughs and stands halfway up. “Yes!” he implores. “Please be prepared! Don’t be like John Fox’s teams!”

A roar of laughter erupts and McMichael goes back to signing.

“You know that old Looney Tunes clip? The one where the circus had been through town and it was just a little street sweeper left. That’s me now.”

To be fair, little street sweepers don’t attract this kind of following a quarter-century after their last day in the big top. This, after all, is a celebration of 99 years worth of Bears history. There is plenty for folks in this giant convention-center-turned-museum to be drawn to. A big chunk of the crowd, though, is waiting for a moment with McMichael.

“In 100 years,” he says, “I’m one of the ones who enjoyed it the most.”

* * *

‘We got off the plane drinking, brother.’

* * *

McMichael understands his popularity would not remain what it is had he not been a part of the most magical sports season Chicago has ever experienced: 1985.

The crowning of those Bears had to come where it came. In New Orleans. A few blocks from Bourbon Street. Where the Bears had spent a January week being exactly who they were — animated hell-raisers off the field and trained assassins on it.

McMichael thinks of his first night in the Big Easy and suddenly gets louder.

“Ohhhh, booyyyy!” he says, leaning back in his chair. “I didn’t realize they put Everclear in those damn Hurricanes at Pat O’Brien’s. It wasn’t long before I was out in the alley, baby. Spewing!”

His eyes bug again as he begins to chuckle.

“And then? We just went to another bar!”

McMichael estimates he had close to 30 family members with him that week, “tagging along like ducks.” Ducks, of course, with VIP access to some of the French Quarter’s most popular watering holes. But come Thursday of that week, with Super Bowl XX closing in, McMichael flipped the switch, turned off the hedonistic urges and stopped going out. Suddenly, his traveling party had more hurdles to clear to continue enjoying their revelry.

“Those (expletives) were in the back of the line,” he says. “I’m thinking, ‘See! See how you should thank me!’ ”

It was hardly insignificant that, even at 28 and in the midst of one of the most fun weeks of his life, McMichael knew how to retain focus. That’s just how that ’85 team was wired. Nothing was going to stop them from punctuating their dream season with another vicious and dominant effort.

When reality sunk in the night before the Super Bowl that beloved defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan was preparing to coach his final game with the Bears, the dejection and sadness smothered the meeting room. McMichael, though, helped block out any human-nature self-pity by impaling a metal chair into the blackboard.

The next afternoon, as the Bears prepared to take the field for the biggest game any of them would ever play, McMichael again took himself to a dark and nasty place.

“It was an out-of-body experience,” he says. “Kevin Butler tells me I was walking around the locker room in some trance and saying ‘Kill these (expletives)! Kill these (expletives)!’ And I don’t remember doing it.”

The defense, to no one’s surprise, went ahead and killed those (expletives).

The Bears allowed their first points of the postseason in the first quarter on a four-play, zero-yard Patriots field-goal drive. They knocked starting quarterback Tony Eason out of the game, then continued to pummel backup Steve Grogan.

At halftime, the Bears had held the Patriots to minus-19 total yards.

By the end of the third quarter they led 44-3.

Seven sacks. Six takeaways.

“We were a train barreling down the track,” McMichael says. “So get out of the way. That’s how you stay safe. You just step off the train tracks. The guys who didn’t got run over.”

McMichael’s only regret from that day was that he was on the sideline unwinding, pulling the tape from his hands in the fourth quarter when backup defensive tackle Henry Waechter sacked Grogan for a safety.

“Ohhhh, brother,” McMichael says. “That could have been mine. And who knows? Maybe if I had gotten that safety, I might have been Super Bowl MVP.”

Still, the win itself was the exclamation point on the most exhilarating season in Bears history. And McMichael knows exactly why that season still resonates with such power across Chicago more than three decades later.

“People view that team as a life event,” he says. “On both ends of the spectrum, good life event or bad life event, people remember everything. You remember exactly where you were sitting. You can see the tchotchkes in the room. Most of life fades. But life events? … What people experienced with that team, they will never forget.”

* * *

‘It was the biggest play nobody saw. They were all headed to the parking lot. The Jets, man. Wooooo. What dumbasses.’

* * *

The Bears were dead in the water that night Monday night in 1991, stumbling toward their first loss of the season. They trailed the visiting Jets 13-6 and when Bears linebacker Ron Cox picked up an unnecessary-roughness penalty with 2:15 left, ABC’s Al Michaels, Frank Gifford and Dan Dierdorf began offering last rites.

“You can write a finish to this one,” Michaels said. “The New York Jets, barring a disaster, will have a very happy plane ride back to Gotham.”

The Bears were out of timeouts. The Jets had the minor task of carefully killing off the final 135 seconds. That would be that.

Until …

Second-and-8, immediately after the two-minute warning. Jets running back Blair Thomas took a handoff and rambled into traffic in front of him. That’s when McMichael shed the block of guard Dwayne White, lunged to his left and plucked the ball out of Thomas’ paws as if he were pulling a grape from its stem.

Fumble forced. Fumble recovered. Bears ball.

“Dumbasses,” McMichael repeats. “All they have to do is kneel down and run the clock out and they decide to run the ball at me? Morons!”

Ninety-nine times out of 100, McMichael admits, he wouldn’t have gone after the football, more focused on getting the running back on his backside. That’s how he was trained. He hated missing tackles.

“But there?” McMichael says. “Game’s over. So what? And I was in position.”

Steve McMichael gestures while talking at his Mongo McMichaels restaurant in Romeoville on April 25, 2019. (Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune)

The Bears turned the takeaway into a last-minute touchdown. They used overtime to steal a 19-13 victory. Damn right McMichael remains proud of that contribution, one of those dig-deep efforts that allowed him to collect one of his 33 career game balls.

McMichael smiles and wonders if maybe he missed his calling. Sure, his 95 career sacks rank third all time among defensive tackles. But maybe he also could have been a takeaway machine for those 13 seasons on the Bears defensive line.

“I’ve come to the realization that I should have started doing the Peanut Punch before Peanut (Tillman),” he says. “Goddamn that’s easy, man! If you’ve got hand-eye coordination, boom! Boom! That ball ain’t ever had a handle on it.”

Still, McMichael is quick to say those heroic moments never felt as powerful as the failures. So he fast-forwards 377 days, to the next season, to the 21-20 road loss to the Vikings that was essentially the beginning of the end of Mike Ditka’s final season as coach.

The Bears blew a 20-0 third-quarter lead that afternoon. Jim Harbaugh’s ill-advised audible and untimely pick-six started the unraveling. But McMichael can still see the Vikings’ winning touchdown playing in his head — Roger Craig on third-and-goal, leaping over the top of the Bears’ defensive line. McMichael was tangled up with right guard Brian Habib and center Kirk Lowdermilk and stood up trying to get his helmet or a hand on Craig. Instead, he was plowed like fresh snow into a heap in the end zone.

“Touchdown,” he says. “We lose the game.”

He sighs and drops a quick PSA.

“Listen up, kids!” he bellows. “On the goal line, keep … your ass … down! Like a crab!”

All these years later the sting of such moments lingers.

“Those are the things that come to a competitor’s mind first. It’s not all the glory moments,” McMichael says. “That’s like raindrops in time, all the great things you did. But it’s the few times you were out there and you (expletive) it up? Those are the first things on your mind, man. That is the fear of failure.”

* * *

‘There is more than enough room on the mountaintop. Come join us, baby.’

* * *

This has been McMichael’s message to Bears teams for the past quarter-century. If there’s any misperception still lingering that the ’85 Bears would love to remain Chicago’s only Super Bowl championship team, McMichael wants it put to rest.

“Everybody thinks we’re standing like legends on the head of a pin,” he says. “Please! Everybody’s welcome.”

Besides, McMichael says, when the current Bears are winning, business is always better for the franchise legends.

After the 2006 season, McMichael told then-coach Lovie Smith that he had to keep going to the Super Bowl. The appearance fees and autograph-signing stipends were rolling in. A great Bears team always beats the alternative.

“The modern-day perception of who the Bears are gets projected on me too,” he says. “In 2014, I was a loser!”

He laughs.

“You know that whole ‘Bear Down’ thing? As bad as they were for the last 10 years, it was like when you hear over the scanner at the cop station, ‘Officer down!’ But it was ‘Bear Down!’ Bears down, all right. Some of those teams were embarrassing.”

Now, though, with this year’s group having legitimate Super Bowl aspirations, McMichael finds himself excited about the season.

He hopes the players in the locker room at Halas Hall understand their opportunity. That rush of game days? It’s never to be taken for granted.

Steve McMichael played in 191 games during 13 seasons with the Bears and retired second on the Bears’ career sacks list with 92.5. (Ed Wagner Jr / Chicago Tribune)

“The roar of that crowd. The hair on the back of your will neck stand up, brother!” he says. “I can see why those Roman gladiators could kill each other for that. Fifty-thousand people in that Colosseum? That roar? Holy (expletive)! That’s a hard wave to squelch down the old bad voice. The duality of man. That savage gets to take over.

“That rush is what brings on superhuman efforts. I see things that have never happened in football happen every week. It’s from that adrenaline, baby.”

McMichael always lived for Sundays. But he now understands he gave it all on the field for Mondays. The film sessions. The weekly peer review.

For those Bears defenses of the 1980s, there was an unspoken and unrelenting desire to make the guys next to them proud. This, McMichael says, was the currency for those teams.

“You do something special in the game, one of us would point it out. ‘Look at that! Run that back! He tore this guy’s ass up!’ ” he says. “And (often) it was on the side of the play where no one saw it. When you take time to point that stuff out, when you’re proud of that guy next to you, more of it starts happening.”

The criticism also became motivating. When McMichael was told he was “acting like a damn Mongo,” he pushed harder to showcase his intelligence.

When Shaun Gayle arrived from Ohio State in 1984, McMichael took notice of the safety’s gut.

“I started calling him ‘Roly.’ It embarrasses him and he hates it so much that he looks like an Adonis with a six pack to this day.”

McMichael chuckles.

“The greatest teams self-police. Our sarcastic humor to each other was born in truth. That little phobia you get? Ooooh, those little phobias will you drive you, won’t they, baby?”

Within that Bears defense, the desire for praise became addicting. The competition elevated.

“Everybody thought we had bounties,” McMichael says. “No. It was incentives. A hundred dollars to whoever gets to the quarterback first. It was never ‘Kill him!’ But now try telling that to a killer.”

There are those wide eyes again.

* * *

‘That’s the beauty of getting old. What you’ve done in the past just gets bigger.’

* * *

Three and a half years ago, after the Streeterville premier of ESPN’s 30-for-30 documentary “The ’85 Bears,” director Jason Hehir let a captivated theater audience in on a little secret. During a post-film panel with McMichael, Mike Singletary and film narrator Vince Vaughn, Hehir wanted his audience to understand this character they had always known as “Mongo,” the guy nicknamed after the brutish “Blazing Saddles” character who cold-cocked a horse, actually had a multitude of deeper layers.

“Honestly,” Hehir told the audience that night, “he’s one of the most intelligent and articulate people I’ve ever met.”

To which McMichael quickly interjected: “You’re ruining the gimmick!”

Indeed, when Hehir set out to make his film, offering a behind-the-curtain glimpse at the brotherhood that drove the ’85 Bears, McMichael was nowhere near the top of his list of “have to have” interview subjects. The young director was so much more eager to dial in with Mike Ditka, with Jim McMahon, with Singletary, with Hampton, with Gary Fencik.

With McMichael? “I was looking for two or three nuggets that’d be good for a laugh.”

Hehir admits he had his preconceptions, preparing to talk to a boisterous former lineman who had also spent several years in professional wrestling. And when they first met, Hehir says “a wind blew through the room.”

“He was loud. He was gruff. And he shook everybody’s hand twice as hard as it had ever been shaken,” Hehir says.

Hehir still refers to McMichael as “a Falstaffian figure,” brazen and cheerful and sometimes bawdy. And yet … “Five minutes into our conversation, you’re getting this Confucian wisdom.”

[ Umpire Angel Hernandez sets record straight on Steve McMichael ejection from 2001 Cubs game » ]

When the filmmakers began peppering McMichael with questions, they became enamored with how much range he had, how he could transition from bombastic and crude shock jock to deeply reflective raconteur.

In discussing the mini-scandal of Super Bowl week — when quarterback Jim McMahon was erroneously alleged to have called all the women in New Orleans sluts — McMichael offered an unnecessary and boorish defense of that purported insult. “Listen, brother,” he said. “When you walk down the street in a town and a girl will show you her boobs for a 20-cent strand of plastic beads? What would you call ‘em? Partiers?”

Yet McMichael also steered the conversation down deeper philosophical paths, professing his undying respect for Buddy Ryan, his sincere admiration for his teammates and making it clear how damn proud he was to have been part of that ’85 squad.

All those players, he explained, demanded greatness from themselves and, in turn, from everyone around them. “That’s when it’s perfect and pure and happiness abounds in that locker room,” McMichael said.

By the time Hehir’s documentary premiered, he understood the ’85 Bears couldn’t have been the ’85 Bears without the blend of passion, sarcasm and viciousness McMichael brought.

“He was the id of that team,” Hehir says. “Of the Monsters of the Midway, he was the ultimate monster. He was the one on that team who reveled in being that kind of animalistic predator. He was the one who reveled in being the loose cannon, the loose screw in that machine.”

McMichael played the role as well as he could.

* * *

‘Here’s something I’m finally ready to admit about the ’85 Bears and myself. We like the limelight, brother. We enjoy being on stage.’

* * *

Yes, Steve McMichael has a verse for “The Super Bowl Shuffle.” One of the most aggravated critics of the stunt the ’85 Bears pulled to record the Shuffle the day after the season’s only loss in Miami, McMichael now gets in on the act.

Some call me Mongo, some call me Ming

Now you’re finding out I can really sing

Hampton and Otis needed a fix

I found out I’m a pretty good mix

We’re going to play it loud, we’re going to break your hearts

You’re going to find out we’re more than three old farts

I didn’t come here to feathers ruffle

I just came here to do this damn Super Bowl Shuffle

You won’t find that verse on the 45 of the original Grammy-nominated song. It’s saved exclusively for on-stage performances by the Chicago 6, the band McMichael is happily a part of with Hampton and Otis Wilson plus musicians John McFarland, Matt Kammerer and Ed Kammerer.

Former Bears defensive lineman Steve McMichael performs with other members of The Chicago 6 in Grant Park on Thursday, July 25, 2019. (Armando L. Sanchez / Chicago Tribune)

This summer, among their many gigs, the Chicago 6 played for a packed house at Ribfest in Naperville and at a July concert at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park.

McMichael sings and plays the rhythm guitar. He can skillfully cover Neil Diamond and Merle Haggard, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Toby Keith. “And when Otis sings Motown,” he says, “I’m a Pip.”

Hampton and Wilson love to needle McMichael as “Foghorn Leghorn.” The scouting reports overlap nicely. Loquacious. Blustery. Full of self-spun wisdom.

“It’s like he’s vaccinated with the Victrola needle,” Hampton says. “He just wants to tell stories. He’ll keep talking and talking. And eventually I have to say, ‘Hey! Hold on! We have to start the next song!’”

When Hampton put the band back together a half-dozen years ago, it was apparent McMichael hadn’t sung for a bit. But then he dialed in. And now?

“On a scale of 1-10, he’s gone from a 5 or 6 to an 8 or 9,” Hampton says. “He has really blossomed. Like anything with Steve, if it means something to him, he works at it.”

For starters, McMichael’s musical endeavor allows him an opportunity to be what he is at heart, a nonstop showman. When he grabs the mic, when he tells a tall tale, when he leans back to belt out some Hank Williams Jr., it all gives him a reminder of “mattering to the throng.”

On top of that, there’s a different rush that comes every time he steps on stage.

“That’s a little bit of the juice I was talking about, man,” he says. “It’s that angst. That’s the best way to describe it. You know you’re about to do something. But is it going to turn out like you want it to?”

* * *

‘When you hit 61, you don’t stop and have any of those long gazes into the mirror anymore. You’ll see flaws that didn’t used to be there. I don’t pose in the mirror anymore. No. No.’

* * *

It has been 24 years since McMichael played his last NFL game. Ironically, of course, for the hated Green Bay Packers. For decades, McMichael has had his at-the-ready quip for curious or still-disgruntled fans who wonder how in the hell one of the most proud and beloved players in Bears history could have even fathomed to put on that green jersey and that cheddar-yellow helmet.

“For 13 years, I helped the Bears beat the Packers every year,” he says. “I whupped their ass, right? So the last year, I went up there on my last leg and I wasn’t any good anymore. So I stole their money and whipped their ass again!”

Even McMichael knows that’s just a convenient wisecrack, concealing the honest-to-God reason he went 175 miles north for his last dance. “I wasn’t in the habit of turning down $500,000.”

Now McMichael is 61 and feeling the effects of his pedal-to-the-metal life. His neck is in constant discomfort. The pitting edema in his knees can be debilitating, like two water balloons filling up. He can no longer mow his lawn in one shot and often tags his wife in to finish.

For the most part, though, McMichael still has his wits and his wit about him — clearly — even as football’s chronic traumatic encephalopathy scourge has engulfed many of his contemporaries.

“And it’s a glass half-full if the brain damage is coming on,” McMichael cracks. “For I have seen things that I would like to forget. They are burned into my memory. Like a pho-to-graph-ic ne-ga-tive, baby.”

Because this remains a family publication, McMichael’s photographic negative can’t be developed here. His tales about Hurricane Hannah or his 1980s escapades on Rush Street will have to remain in the darkroom.

Naturally, that was also the approach in 2004 when the former Bears great wrote his first book: “Steve McMichael’s Tales from the Chicago Bears Sideline.”

Steve McMichael shows off a copy of his book on the 1985 Bears during the Chicago Tribune’s “Chicago Live!” event at the Chicago Theatre Downstairs on Feb. 10, 2011. (Chris Sweda / Chicago Tribune)

“I had teammates calling me up, ‘You didn’t put my name in there, did you?’” McMichael says. “No. I did not. I kept us all heroes, brother. I can still make a lot of money being a hero.”

Still, it’s evident McMichael enjoyed himself back in the day.

“Ooooh, the skulduggery,” he says. “It was almost like devil worship!”

He laughs and pauses for a moment.

“Ohhhh, brother, did we have fun! Poor Honey Bears got fired!”

After football, McMichael tried pro wrestling. And then he coached the Chicago Slaughter to a Continental Indoor Football League championship. Later, he ran for mayor in Romeoville and lost.

Now McMichael has moved on to a different chapter. Yes, he is retired. But he still has the band plus his duties as a restaurant owner at Mongo McMichael’s in Romeoville plus a Sunday morning pregame radio gig to keep busy. And even though he has lost 40 yards off the tee box, he’ll happily accept most any invitation to play in a golf event.

Football once was McMichael’s obsession. But it also forced him to be single-minded and necessarily selfish. Now he can spread his wings.

He is, in his own words, “the happiest I’ve ever been in my private life,” enjoying time with Misty, his wife of 18 years, and his 11-year-old daughter, Macy.

Macy was born with the McMichael smart-ass gene. A few years back when father and daughter were playfully wrestling, McMichael used his leverage to get the upper hand.

“Don’t worry,” he told his daughter. “One day you’re going to be tall like Daddy.”

Replied Macey: “But not as fat, right?”

McMichael was both insulted and deeply proud.

McMichael insists he never could have been a dad when he played. It would have made him way too soft, bringing out the sensitive side he now has to use when chaperoning school field days, overseeing sleepovers and driving his daughter and her friends to the mall.

“We have to go into every kids store,” he says. “The McCaskeys didn’t pay me enough.”

There’s a young neighborhood boy from down the block who frequently rings McMichael’s doorbell looking for Macey. And whether she’s home or not, McMichael delivers the same message.

Not today, son.

The doorstep is now his 50-yard line.

“Like stray cats coming around here,” he says. “Jesus. I’ve got my stun baton ready.”

* * *

‘If I wouldn’t do it all over again, what would I have to remember? I would do it all over again because that is what defines me. Going out and playing that game was worth every pain that I’m in right now.’

* * *

With what’s left of the nacho pile getting cold, McMichael senses an obligation to punctuate his sermon. Suddenly, he is right back in another milestone moment: his first day as a Bear and that first visit to George Halas’ office.

“It was like I was walking into a 1920s gangster movie and he was James Cagney,” McMichael says. “And you know what he said to me? ‘I’ve heard what kind of dirty rat you are at practice. Don’t change, see!’”

McMichael grinned and nodded at the Bears owner. The message was received.

“He wanted me to stir those (expletives) up,” he says. “He knew (going) half-ass wasn’t going to pay the piper.”

McMichael’s career took off from there with an effort to prod his teammates and challenge himself plus an internal push to make Buddy Ryan proud.

McMichael gladly points out he was the third man to sign the famous letter defensive players sent to Halas in 1981, pleading Ryan be kept around as coordinator when head coach Neill Armstrong was fired.

Former Bears defensive tackle Steve McMichael wears two championship rings, including his Super Bowl XX ring. (Erin Hooley / Chicago Tribune)

McMichael had long respected Ryan’s accomplishments — as the defensive line coach for the Super Bowl champion Jets and later for the “Purple People Eaters” in Minnesota. He was magnetized by Ryan’s leadership style and motivated hourly to win him over.

“I knew I needed him to stay around long enough to play me. Then I knew I had done something, when that old man trusted me.

“It was never your talent he was worried about. It was whether you were too stupid to play for him.”

McMichael started as “76” — just a number to the defensive boss. By Super Bowl XX, he had become “Tex,” a key part of the leadership nucleus that legendary defense needed to realize their full potential.

In the latter stages of Ryan’s life, Hampton and Fencik went to visit their ailing coach on his farm in Kentucky. During the stay, they called McMichael. Ryan jumped on the phone and greeted one of his favorite players with all the energy he could muster.

“Come out of that huddle, Tex!”

Even then, with McMichael in his late 50s, that small show of affection felt invigorating.

Says Hampton: “Just like a child wants his parents’ approval and acceptance, Buddy had a knack for making you want to be accepted by him. Almost 30 years later, that was still the same pat on the head we all wanted.”

For those bold enough to label the ’85 Bears a one-hit wonder, to question why only one Lombardi Trophy is on display at Halas Hall, McMichael suggests they kick rocks.

“Maybe everybody should be happy as a two-peckered goat that a bunch of slappies could win one,” he says.

He points to a five-year stretch from 1984 to 1988 when the Bears won 62 regular-season games and five straight division championships. In the Super Bowl era, the organization hasn’t had another half-decade stretch that’s even in the same stratosphere.

But that’s all just bar chatter.

What means so much more to McMichael is remembering how alive he always felt chasing excellence.

“A gambler doesn’t place the bet because he wants the juice of winning,” McMichael says. “The juice happens when he places the bet and he still doesn’t know if he’s going to win or lose. That’s the juice.”

He’s smiling again.

“If you really want to enjoy your life and get everything you can out of it,” he says, “make sure you understand that it’s the journey that’s the reward, baby. It’s not the destination. The journey is what makes you who you are. The mountaintop is great. But how you got there is what you remember.”

Maybe he has found the meaning of life after all.

Dan Pompei is a senior writer for The Athletic who has been telling NFL stories for close to four decades. He is one of 49 members on the Pro Football Hall of Fame selectors board and one of nine members on the Seniors Committee. In 2013, he received the Bill Nunn Award from the Pro Football Writers of America for long and distinguished reporting. Follow Dan on Twitter @danpompei

May 6, 2024

The doorbell rings, and it feels as if the sun has broken through the clouds. The dogs rush to the front door. There’s Blue, the yapping chihuahua, and Marshmallow, the Shiba Inu with a limp. And here comes Misty McMichael with a big smile and a big hug.

A visitor has arrived, and Steve McMichael is as buoyant as someone in his situation can be.

Whoever is at the door undoubtedly will bring up his upcoming induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and if he could still smile widely and proudly, he would.

For a while, McMichael derived pleasure from Haagen-Dazs vanilla ice cream in his feeding tube, but he was cut off because it made him vulnerable to pneumonia. For now, he can experience flavor only in ice chips — Pedialyte, cranberry and Coca-Cola.

These days, satisfaction is scarce and pleasure is mostly a memory.

Three years into a diagnosis of ALS, McMichael, the former Chicago Bears defensive tackle, is about one year beyond when doctors said he might expire. He can’t move his legs or arms. Misty, his wife, has rushed him to the hospital at least 10 times over the last few years, always with dire fear.

He hasn’t been able to communicate verbally for about a year, but he expresses simple sentences through a speech-generating device that reads eye movements. The machine has a few phrases saved that he uses frequently.

“Ass on fire,” he makes it say often, a plea to address a recurring pain.

“More meds,” is another.

If the visitor is expected, he often won’t ask for more meds to ensure he isn’t foggy. There is a lot that McMichael can’t do anymore, but he can still connect with the people who have been important to him.

Some people ring that bell once. Some do it every so often. Some ring all the time.

They experience humanity and intimacy in a way they never have.

In the living room is a gray reclining chair.

It was bought so Steve’s sister Kathy McMichael would have a place to sleep in 2021 and 2022 before he had 24-hour medical attendants.

As well as anyone, she can soothe his pain.

She holds his hand and talks about old memories, including games she saw him play going back to high school. Sometimes they watch a YouTube compilation their sister Sharon put together with videos of him playing football at various levels, wrestling, singing and more.

Staying with him for extended periods has been easy for her. Leaving, not so much.

“When I was there, I tried to be upbeat for him,” she says. “But when I was leaving, I thought he would die and I would never see him again. I would cry all the way home on the plane and spend the next two days in bed crying.”

Kathy McMichael, right, calls big brother Steve her hero. (Courtesy of Kathy McMichael)

When Kathy was a toddler, Steve — “Stevie” she calls him — played dolls with her. She had a Barbie; he had a G.I. Joe.

“I have the fondest memories of him,” says Kathy, who is a legislative director for the Texas attorney general’s office. “People don’t realize how kind and sweet he is. He’s always been my hero.”

For most of their lives, they talked almost daily on the phone. When Kathy went through a divorce at 26 and was so upset she couldn’t eat, Steve showed up with a U-Haul to move her, set her up in a new apartment and took her out for a meal every day for a couple of weeks. “He saved me and it turned my whole life around,” Kathy says.

She was with him in February for the announcement that he would be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Kathy thought he didn’t look good at the time. She couldn’t see the lovely green in his irises. She feared the worst.

Now, Kathy thinks differently. “He’s not ready to go,” she says. “We’ve talked about it. I don’t know that he ever will be. He doesn’t give up on anything. It’s not in his makeup.”

She’s looking forward to traveling to Canton, Ohio, for the induction, but if Steve can’t go, Kathy will be at her big brother’s bedside.

When Mike Singletary first visited McMichael after his ALS diagnosis, they prayed together.

“My hope was he could get healed,” Singletary says.

That isn’t happening, but the middle linebacker keeps praying with his teammate. Even now, there are blessings to be thankful for, and more to request.

Singletary tells stories, too, hoping to see that old spark in McMichael’s eyes. He talked about a 1984 game against the Raiders in which McMichael, Singletary and company knocked out quarterbacks Marc Wilson and David Humm. Next up was supposed to be punter Ray Guy — but he refused to go in.

“He loved it,” Singletary says. “It’s kind of like reading a bedtime story.”

One day Singletary told him how much he always appreciated him, how much he meant to him, and how he felt he could always trust him. When they were playing together, Singletary said, he always knew where McMichael was going to be.

McMichael tried to respond using his speech-generating device. He tried and tried, but he couldn’t get it to do what he wanted it to.

“He got so frustrated that he started crying,” Singletary said. “That was a tough moment.”

A world traveler, John Faidutti has been to Egypt, Russia, Thailand, China, the United Arab Emirates, Argentina and many other destinations. He has climbed Mt. Rainer and Mt. St. Helens.

But he hasn’t traveled in almost three years.

“I’m afraid of leaving because if Steve dies when I’m gone, it will kill me,” he says. “I have anxiety about that.”

Faidutti, an investor, met McMichael about 25 years ago at a party and bonded on summer afternoons at a swimming pool outside of the apartment complex where McMichael lived. When Misty gave birth to Macy 16 years ago, Faidutti was in the delivery room. Steve asked him to be her godfather and started calling him “Padrino,” Italian for godfather.

“Now you’re in the family,” Steve told him. “Once you’re in the family, you can’t get out.”

When Macy started talking, she couldn’t say “Padrino,” so she called him “Drino.” Now, everyone knows him as “Padrino” or “Drino.”

Before Steve lost the ability to speak, Padrino asked him what he could do for him in the future. “Just take care of Macy,” Steve told him.

As Steve has been progressively unable to do what a father usually does, Padrino has done more.

John Faidutti, left, has embraced his role as godfather to Macy McMichael, Steve’s daughter. (Courtesy of John Faidutti)

Macy is a shy girl, but not around Padrino. On “Macy’s day,” which happens once or twice a week, he takes her to a restaurant for food. They play video games together. He helped teach Macy to drive.

Padrino makes sure Steve knows everything that’s happening with his daughter. She’s very artistic, and she shows Padrino her creations. Padrino makes sure Steve sees them.

Padrino tied Steve’s shoes back when he wore them. He shares his Prime Video password. He’s removed Steve’s catheter. He’s changed his diapers. Giving his friend comfort is a privilege, not a burden. “I have no problem doing whatever he needs me to do,” Padrino says.

Many times, it has seemed the pen was almost out of ink for McMichael. But then it keeps writing.

Every time he’s had a medical emergency, they ask him to blink once if he wants to go to the hospital to be treated or twice if he wants to let it be. McMichael always has blinked once.

To Padrino, McMichael repeatedly has indicated he wanted to keep living.

On McMichael’s 66th birthday last October, Padrino told him, “Let’s make it one more year.”

In his eyes, Padrino saw determination.

Ric Flair hasn’t seen McMichael in about a month and a half because he’s been traveling. He plans to visit him soon.

When he comes, Flair tries to limit his time with McMichael to about 30 minutes because he can’t take much longer.

The visual can be unsettling.

Except for McMichael’s spirit, everything about him is withered.

“It’s very difficult for me to see him like that,” Flair says. “It’s so hard. My job when I’m there is to make him smile and laugh, and make him know people care about him. I walk away thinking I’m the luckiest guy in the world not to have something like that.”

Pro wrestling great Ric Flair, right, with Misty and Steve McMichael, calls Steve “one of the greatest guys I’ve ever known.” (Courtesy of Misty McMichael)

Flair and McMichael started out as enemies. In 1996, McMichael was a commentator for WCW wrestling when Flair hit on his then-wife, Debra. McMichael, with former NFL player Kevin Greene, subsequently challenged Flair and Arn Anderson to a tag-team match. But instead of exacting revenge on Flair, McMichael took a heel turn, attacking Greene and joining forces with Flair, Anderson and Chris Benoit as “The Four Horsemen.”

“When he came on board, his personality won me over in five seconds,” Flair says. “It’s bigger than life. He’s one of the greatest guys I’ve ever known.”

To Flair, McMichael was more than a wrestling partner.

“We hung out every night, partied and drank,” he says, laughing. “You kidding me? I spent New Year’s Eve one year with him and Lawrence Taylor in Las Vegas. Tell me about it. Steve can be something else. He gets away with it because he’s Steve.”

Not many could hang with the legendary “Nature Boy” after hours. But Flair claims to have struggled to keep pace with McMichael, who showed up every Monday for five days on the road with $15,000 in cash in his pocket, saying, “I’ve got more money than I’ve got time.”

They were bonded in the wildest of times. Now they share the most tender moments.

Flair looks forward to partying with McMichael again in Canton at McMichael’s induction.

“If they bring him up on the stage, I think that will be one of the most emotional, fulfilling moments,” he says. “It will be one of the most powerful things I will have seen.”

During his playing days, McMichael hired Michael Kinyon, a friend of teammate Kevin Butler’s, to hang mirrors at his house. Kinyon owns Michael’s Glass and also takes sideline photos for the team.

Their relationship grew, but it took time.

“I was a little afraid of the guy initially, honestly,” Kinyon says. “For an outsider like me, it probably took a year and a half of hanging around with him almost every week before I felt comfortable.”

The turning point came when he was with a group of Bears players in a private room at a golf outing and a photographer from the event came in to take pictures. McMichael charged at him and told him to leave.

“We’ve got our own photographer,” he told him, punching Kinyon in the chest, sending him stumbling and leaving a bruise.

Butler turned to Kinyon and said, “You’re in.”

After McMichael was stricken with ALS, Misty asked Kinyon to install mirrors so she could see him in his bedroom from her bedroom.

Kinyon often brings liquid CBD and THC to put in McMichael’s feeding tube. It helps with the pain and anxiety.

On a recent visit with former Bears equipment man Gary Haeger and defensive tackle Jim Osborne, they brought up a 1984 game. Quarterbacks Jim McMahon and Steve Fuller were injured, and Mike Ditka had no choice but to play Rusty Lisch.

Then McMichael set his eyes on the screen of his speech-generating device and worked diligently. Minutes passed.

And it was McMichael who dusted the cobwebs from the tale and delivered the zinger.

“Ditka cut him on the plane ride home,” he said through the machine.

Laughter, loud laughter.

Dan Hampton often brings mutual friends to visit McMichael.

In numbers, there is comfort.

They go around his bed and try to bring him cheer.

“Normally, his eyes are laden and sad,” Hampton says. “But if you tell a good story, his eyes light up.”

Lifting his spirits is one thing. Lifting his body is another.

When he still could speak, McMichael sometimes asked to be held upright to stretch. But lifting him was like lifting a 175-pound sandbag, and hardly anyone had the strength and assuredness. Hampton, who still looks like he could bull rush through a double team, would do it for close to a minute. He can’t do it anymore because McMichael, who now weighs about 150, doesn’t have enough core strength. “I’d have to squeeze him so hard to pick him up, I’d be afraid I’d break something,” Hampton said.

McMichael has called Hampton his big brother.

Steve McMichael has called former Bears teammate Dan Hampton his big brother. Hampton built a wheelchair ramp at the McMichaels’ house after Steve’s ALS diagnosis. (Courtesy of Michael Kinyon)

When McMichael arrived in Chicago to sign his first contract with the Bears, Hampton was sent to the airport to pick him up. They came together like two pieces of flint, and the fire they created burned spectacularly.

They raised hell between the tackles and then did it between sips of Crown Royal.

Hampton and McMichael became the true colonnades of Soldier Field, and the dominating Bears were built upon them. The night before Super Bowl XX, an emotionally charged McMichael threw a chair at a blackboard with such force that all four legs stuck. Then Hampton bashed a film projector to pieces.

ADVERTISEMENT

In another era, it seemed as if they controlled everything around them. Things have changed.