Tom Landry

Tom Landry: Longhorn For Life?

by Larry Carlson for https://texaslsn.org

He was a mythical figure on the NFL sidelines. He was one of pro football’s brightest, an innovator without peer, and frequently described as aloof. Laconic. Cold. An automaton.

Perhaps most famously, one of his best players, running back Duane Thomas, in 1970 called him, “…a plastic man…no man at all.”

For almost three decades, football fans knew him from sportscasters as “the only coach the Dallas Cowboys have ever had.”

Tom Landry, tall, fit, unsmiling beneath the trademark fedora, is an iconic NFL figure more than 35 years since he coached his final game, almost a quarter-century since he died. Hired in 1960 as the Dallas expansion team’s head coach, he was not yet thirty-six years old. Youngest boss in the National Football League.

What many football aficionados do not know, never knew, about the enigmatic coaching whiz, is that he played college football for the Texas Longhorns.

Landry grew up in the Rio Grande Valley and quarterbacked the Mission Eagles to a 12-0 season as a senior. He would soon enroll at The Forty Acres. But World War II quickly caused a shift in his priorities, away from classes and football to serving in The Army Air Corps.

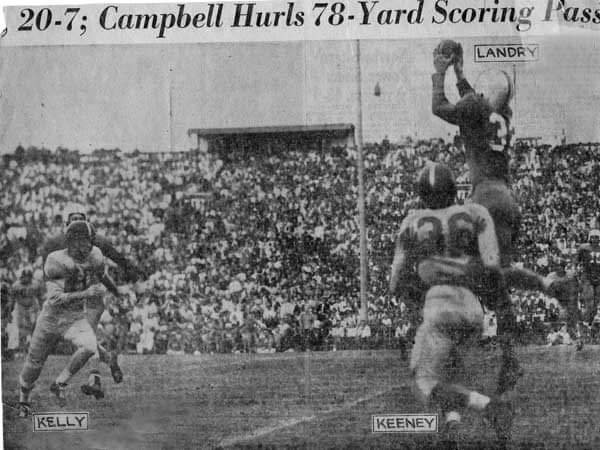

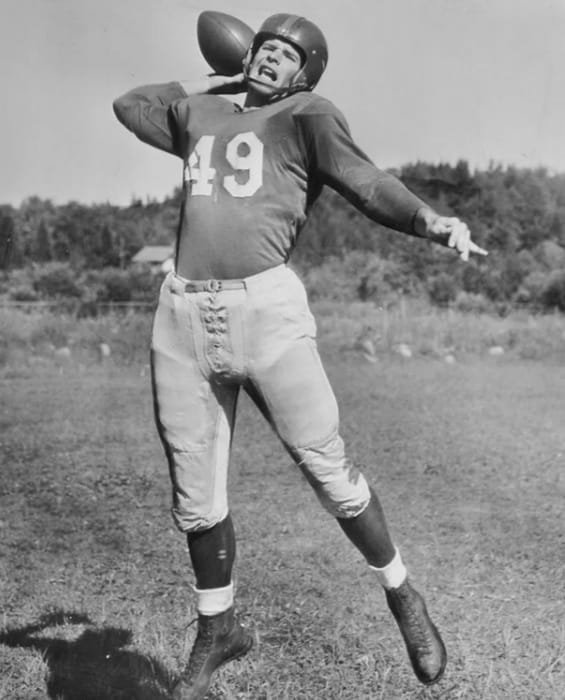

Landry flew 30 missions as a bomber pilot and survived a plane crash in Belgium, After the war, as an industrial engineering student, he would earn a degree at UT. Big, at 6-1, 195-pounds, the South Texan was a standout punter and fullback for the Longhorn teams of 1947 and 1948. Those squads finished as Sugar Bowl and Orange Bowl champs, whipping Alabama and Georgia, respectively. A captain for the ’48 Horns, Landry ran for 117 yards in his final college game.

It is easy to fast-forward through four more decades of football and peruse the NFL years and the coaching legacy Landry left behind. But a question…has Landry ever been irrevocably linked to the Texas Longhorns?

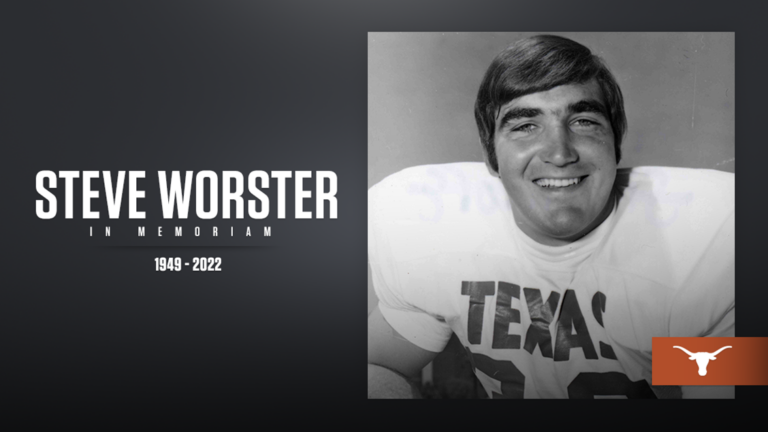

Bobby Layne, a Landry teammate on the aforementioned Sugar Bowl champs always was. Tommy Nobis was. Earl Campbell? Of course. As were a host of others who lived on as beloved “Longhorns for Life,” in the manner of James Street, Steve Worster, Ricky Williams, Vince Young and Colt McCoy.

As I prepared this article for TLSN, I realized I had never seen a picture of Coach Tom Landry, flashing the “Hook ’em Horns.” He, of course, was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame, the Texas Sports Hall of Fame and the UT Hall of Honor.

For the record, the famous hand signal wasn’t even invented until the mid-fifties, introduced by a Texas cheerleader and future State District Judge, Harley Clark. But this writer could not recall ever hearing of a congratulatory call from Landry to Darrell Royal, upon the latter’s winning of national titles in 1963, 1969 and 1970. That certainly does not mean it didn’t happen. Or that Landry did not still check the college scores. But did he and DKR ever meet, other than as opposing combatants in the Texas-OU wars of the late ’40s?

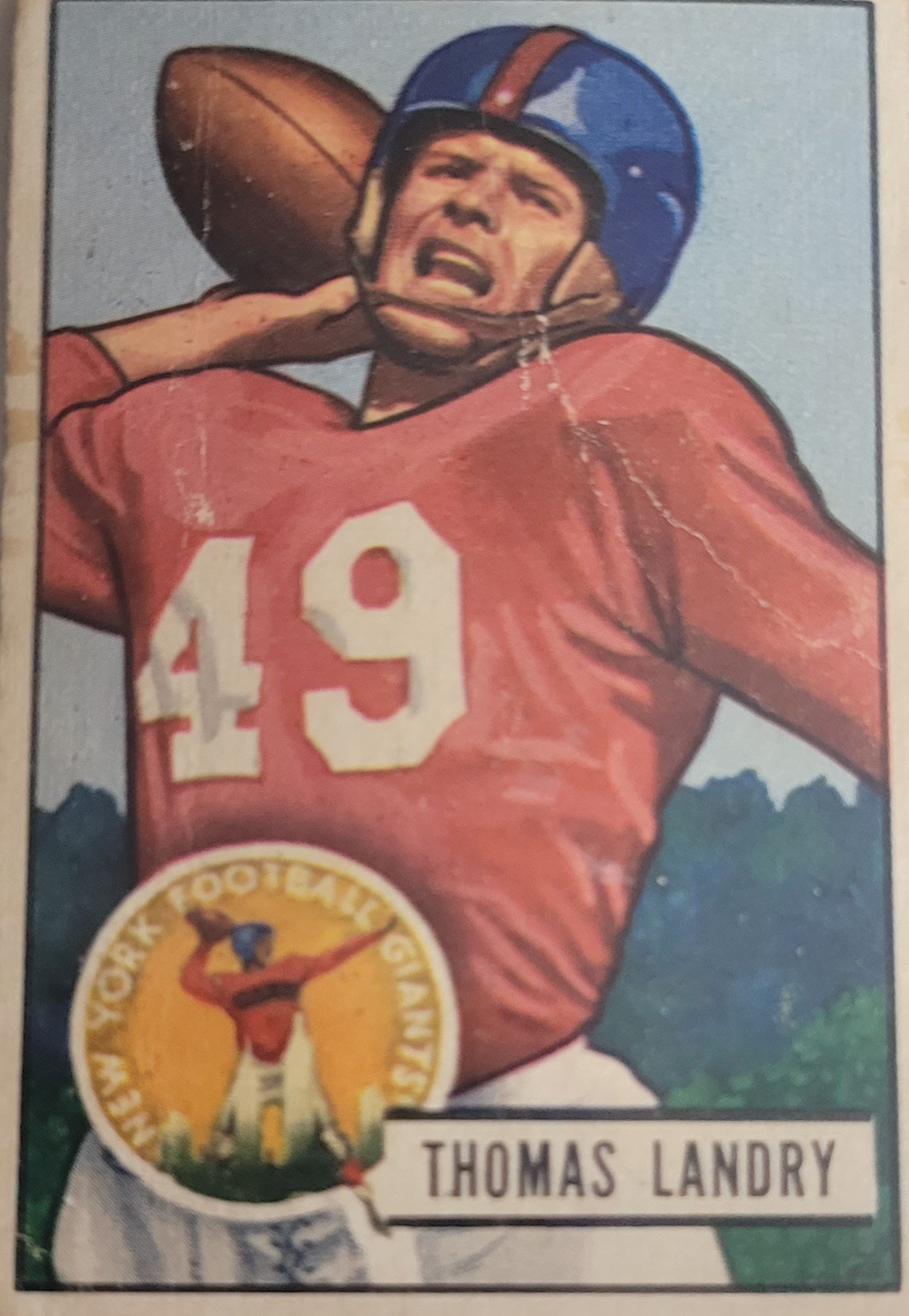

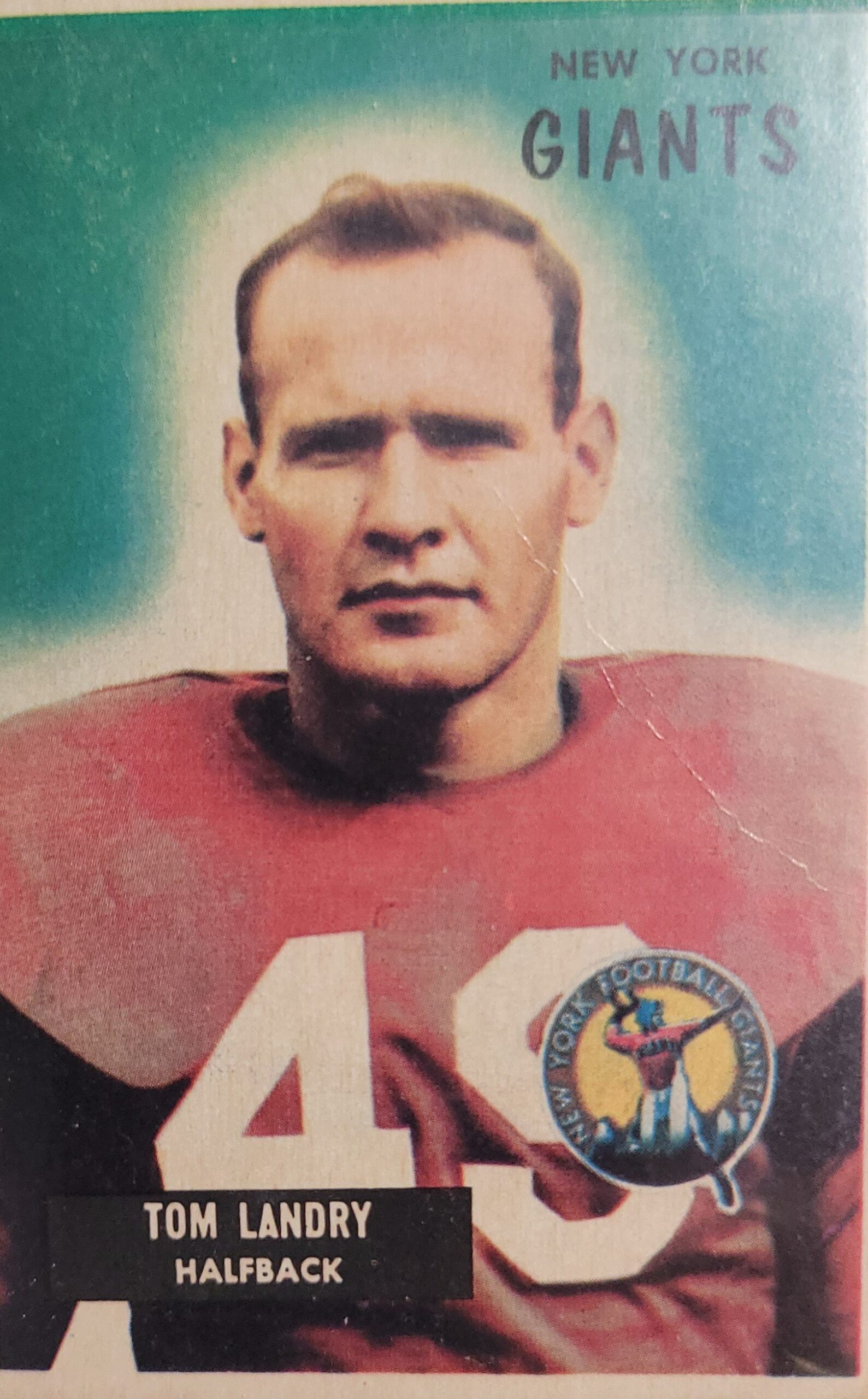

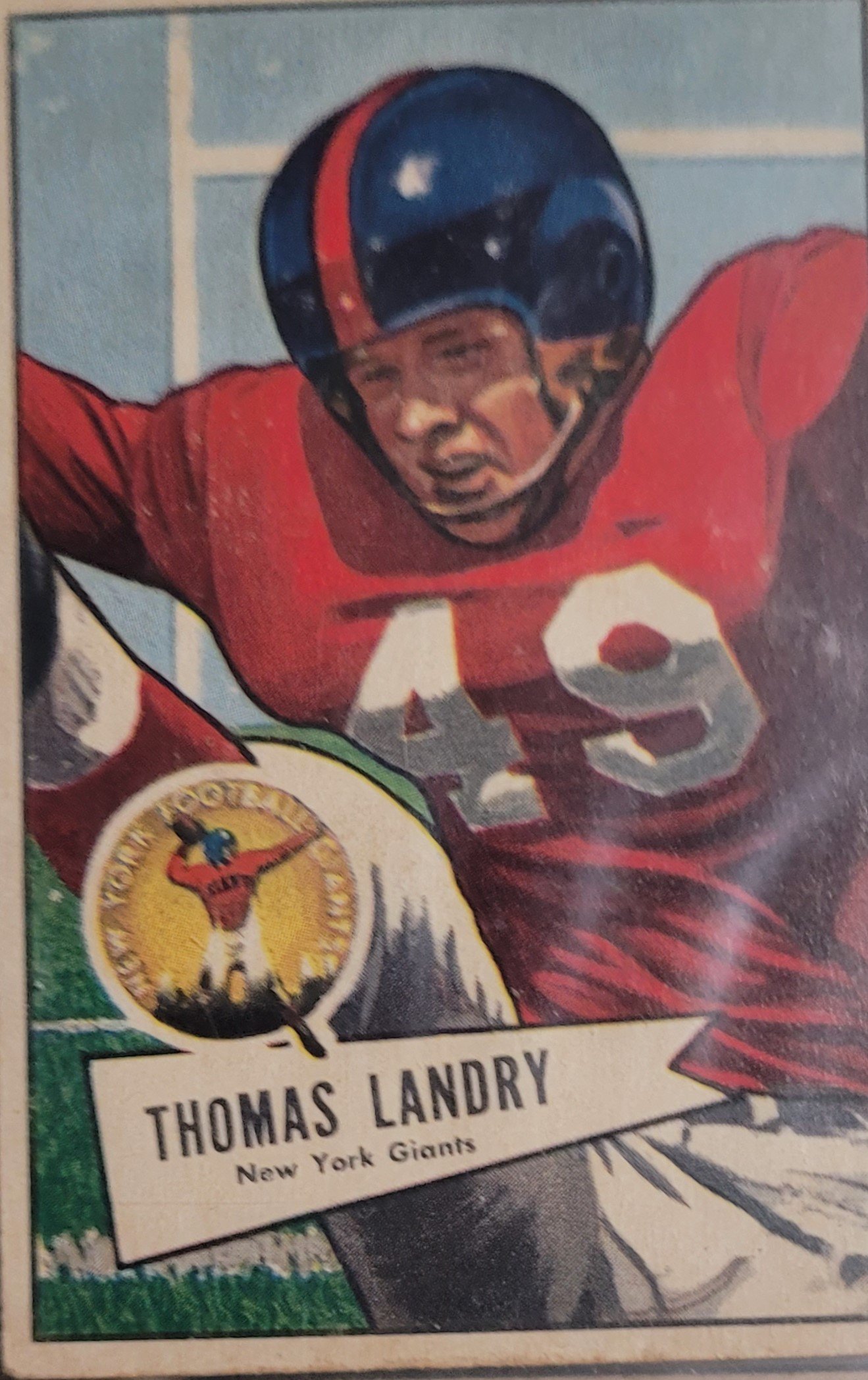

Landry was only a 19th round pick of the All-America Football Conference’s New York Yankees in ’49, and a 20th round selection of the New York Giants. He played one season for the Yankees, then moved across town to play and/or coach for a decade with the Giants, known for luminaries such as Charlie Conerly Frank Gifford and Sam Huff.

Landry was All-Pro as a defensive back and renowned as an excellent punter. He assessed himself as slow afoot and said his lack of speed conditioned him, mentally, to be a step ahead in seeing where a play would go. That attitude, and adjustment, foreshadowed his coaching style. Playing only six seasons – the last two as a player/assistant coach the Texan was literally “a coach on the field,” heady and anticipatory. He intercepted 32 passes in just 80 NFL games.

Stepping away from playing, Landry took over as New York’s defensive coordinator, serving opposite the offensive coordinator, Vince Lombardi.

Image-wise, it is hard to imagine more diametrically opposed players, at least off-the-field, than Bobby Layne and his UT backfield mate. Or to ponder a pair of coaching attitudes more dissimilar than Lombardi’s and Landry’s. Layne was the good-timing bad boy who never lost a football game, just “ran out of time” once or twice. Even was known – as a baseball pitcher who went 28-0 in Southwest Conference play – to have one day guzzled an iced-down bottle of beer per inning to fight off pain from a foot with fresh stitches. And the result? A no-hitter against the Aggies in College Station.

As for coaching styles, the fiery Lombardi, king of the Green Bay Packers’ reign, was famed for his verbosity and feverish rants, the antithesis of Landry. Back in his home state in 1960, the man from Mission brought a New York aura that belied his Lone Star upbringing. Impeccably clad in custom suits and topped by an ever-present fedora, Landry more closely resembled a Wall Street accountant than a football man. He was buttoned-down and tight-lipped, never one to display sentiment. “You can’t call a play and make critical decisions if you’re emotional,” he once stated

.

Head-coaching matchups between the two former Giants coordinators would become the stuff of legends, especially in “the Ice Bowl,” with Lombardi’s teams claiming victories.

While Lombardi was known as a master motivator, Landry brought a reputation as an innovator to Big D. He was mastermind of the 4-3 defense, then reinvented his own philosophy and brought on the ingenious Flex Defense.

Landry’s creation took away the “fly to the ball” mentality and demanded recognition of offensive patterns and tendencies. It was at first criticized by media types and sometimes frustrated fans. And it did not translate well to all players.

Former All-Pro Herb Adderley was acquired by the Cowboys after championship years with Lombardi in Green Bay. Talent, leadership and a nose for the football were his calling cards. But in short time, he was curtly demoted by Landry, after alertly, expertly breaking up a pass in the end zone.

Thus shunned for what would normally bring plaudits, an incredulous Adderley rhetorically asked his new head coach if he was just supposed to let a receiver blow past him to the end zone.

“Yes,” a stone-faced Landry asserted. “If that’s what your keys tell you to do.”

Following his retirement, Adderley later spilled frustration to some reporters. “Tom Landry had a bitterness in his heart for me. After all I did for that team, I’ll never understand it.”

More than a few reports surfaced over the latter half of Landry’s twenty-nine seasons (1960-1988) in Dallas, that he could indeed smile, even laugh and take a joke. But his stern manner and tendency not to reassure players of their value and abilities drove some talented players out of town. Most notably, it pushed QB Don Meredith to an early retirement.

One anecdote from a ’60s training camp stands as “exhibit A” regarding Landry’s “all business” mentality. When Meredith threw a “wish I had that one back” pass in practice that was picked off by Cornell Green, “Dandy Don” took off his helmet and comically ran after his teammate, wielding his helmet as a weapon. Players reportedly broke up laughing and then went back to work.

But they were set straight later in a team meeting.

“Gentlemen,” the coach reportedly told his troops, “nothing funny ever happens

on the football field.”

Meredith, of course, in 1970 became a bigger star on ABC-TV’s newly-minted “Monday Night Football,” as analyst, free spirit and tormentor of Howard Cosell. The Cowboys got annihilated, 38-0, by the St. Louis Cardinals on national TV one October evening and it is easy to picture the former SMU star feeling that something pretty damn funny was happening to his old coach, even as Meredith no doubt empathized with his former teammates. Worth noting: That same Dallas team did play in January’s Super Bowl V, though they lost a close one to the Baltimore Colts.

Pat Toomay was a Vanderbilt-educated defensive end for Landry’s Cowboys for five of his ten NFL seasons, and later wrote many football-related articles and two books. He was generally even-handed in his assessment of Tom Landry. But in one article, he cited what was often considered the coach’s brusque manner.

“On the field, a technical failure to conform could lead to a chilling dismissal,” Toomay wrote, adding that “a need to create and mold an image of themselves out of their respective environments” was another perceived flaw in Landry’s and other coaches’ make-up.

Players-turned-writers frequently have taken to the quill or keyboard to dissect and criticize their former coaches. Onetime Longhorn Gary Shaw, a squadman during the mid-sixties, ripped Texas coach Darrell Royal in his “tell-all” book entitled “Meat On The Hoof,” in 1972. The Texas Legacy Support Network’s site has chronicled some of the impact and fallout from that work.

If Tom Landry had a “Gary Shaw” former player, it was erstwhile tight end Pete Gent, who went on to fame as a novelist (the best-selling “North Dallas Forty” and more). Landry classified himself as a born-again Christian, one who faithfully attended services at Highland Park Methodist Church. He counted Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell among his friends.

But Gent didn’t cotton to Landry’s reputation as a religious man. “This Christianity kick is a method to defend himself against the incredibly un-Christian things he does to the people who work for him, so he can play with their minds and then forgive himself,” Gent wrote. “I just don’t believe a man can preach moral ethics and do what he does.”

In turn, Landry opined that there was nothing about Christianity and toughness on a football field that didn’t mix. “Christianity and pro football are very compatible…it’s a matter of intent,” Landry said. “If you’re vicious and want to hurt people, that’s bad. But you don’t often find that feeling among athletes,” he concluded.

Supporters of Landry regularly defended his ways. Star quarterback Roger Staubach, himself known as a God-fearing man, was just one of many who saw past the coach’s outward demeanor. “Tom may be personified as cold,” said number 12, “but he would give you the shirt off his back if you needed it.”

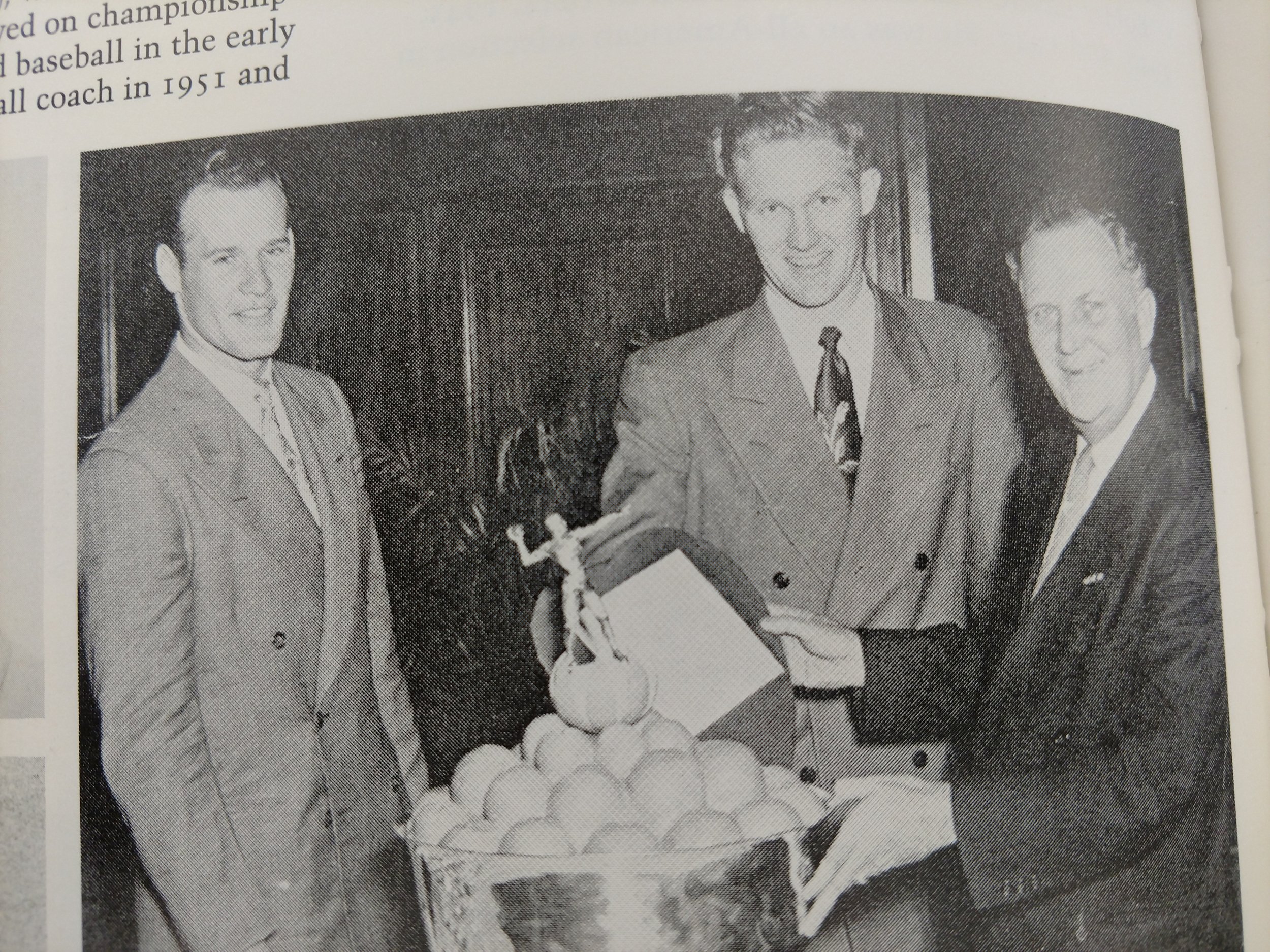

Rooster Andrews had been UT’s pint-sized placekicker/manager after WWII, roomie and best buddy of Bobby Layne and teammate of Landry. A quarter-century after they played together, Sports Illustrated asked Rooster about his impassive, long ago teammate, the Cowboys’ Super Bowl-winning coach.

“People want to know what makes Tom tick,” the Austin sporting goods magnate and Longhorn ambassador said. “And he’s too smart to tell them. He was born polished,” Rooster testified. Then he told the magazine’s writers that Landry didn’t frown on the pranks and hijinks of Layne and his legions, he just didn’t participate.

“Landry wouldn’t let you upset him and he wouldn’t upset you.”

Ardent Cowboys fans, and NFL followers of a certain age, can recite the enviable records and achievements of the Lone Star coaching legend. In spite of heading up a unit of cast-offs for a new franchise, not charting a winning record in the franchise’s first six seasons, Landry’s teams won 250 games. Few of them came in his last three seasons before Jerry Jones bought the team and unceremoniously dismissed the strong, silent UT grad who piloted the Pokes to five Super Bowls, winning two of them. The one figure most synonymous with the Cowboys, dubbed “America’s team,” had led the franchise to twenty straight winning seasons in between the unsatisfactory ones. That mark is likely as safe in NFL annals as is Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in baseball marks.

One more topic, though. With Landry at the helm, the Cowboys seemed to avoid drafting Longhorns. They took big tackle Don Talbert in the eighth round in ’62 after their second season. And in ’64, the ‘Pokes chose the Longhorns’ first Outland Trophy winner, Scott Appleton as the first round’s fourth overall pick. But not really. They had worked a deal with Pittsburgh to acquire receiver Buddy Dial, and immediately shipped the rights to Appleton to the Steelers. Also the first pick of Houston’s AFL team, Appleton signed with the Oilers.

Perhaps Landry did not have the final say in draftees, anyway. Tex Schramm, the larger-than-life GM in Big D, was likely the bull goose when it came to who was drafted and when.

It was twenty-three years before Dallas again took a shot at a Texas-ex within the first ten rounds of the draft. Wide receiver Everett Gay was the ‘Boys’ fifth-round choice in ’87. Bucking the NFL strike, Gay caught 15 passes in the strange season that fall. Injuries kept him from playing again. Scarcely a year later, Jones took ownership and Landry was coaching history. Literally.

There is no debating Landry’s impact on what became a mega-billion dollar franchise, or on the NFL at large. He was at once ahead of his time and still acutely of his era as a trendsetter and outside-the-box coaching mind. The man in the fedora even became the stuff of pop culture. In TV’s “King of the Hill,” set in fictional Arlen, TX, Hank Hill’s son, Bobby, attended “Tom Landry Middle School.”

Some years later, when Buzz Bissinger’s “Friday Night Lights” book had already been adapted for a movie, it then became a hit television series. It could not have been by accident that one player for TV’s mythological Dillon Panthers, portrayed by Texas actor, Jesse Plemons, had the first name of Landry.

(Writer’s note: Longhorn fans no doubt also noticed that Dillon’s first quarterback was named Street, and a later QB was McCoy.)

But one question regarding the NFL legend can still be tossed around, a political football as it were, among Longhorn backers. Once Tom Landry left the Capitol City of Austin…just how orange was his blood?

Well, the blood of his grandkids need not be tested. Some fifty years ago the coach gave his daughter, Kitty, at the altar, to a guy with pretty solid burnt orange credentials. Name of Eddie Phillips. Landry’s son-in-law and the father of the coach’s grandchildren quarterbacked the 1970 Longhorns to a national title.

And it is absolutely on the record that the coach who would become an NFL Hall of Famer and “Mount Rushmore” figure did indeed stay involved with UT football. One former Texas player told me of Landry’s participation in a Longhorn team banquet in the early ’70s that took place not long after the Cowboys had claimed their first Super Bowl title. That player said Landry helped award letters to Texas players, smiling and enjoying himself greatly throughout the evening.

And his footwear?

Boots, not wing-tips.

(TLSN’s Larry Carlson teaches sports media at Texas State University and lives in his hometown of San Antonio. He is a member of the Football Writers Association of America.)

Thoughts on the years of the photos below are welcome.

TLSN TLSN TLSN TLSN TLSN